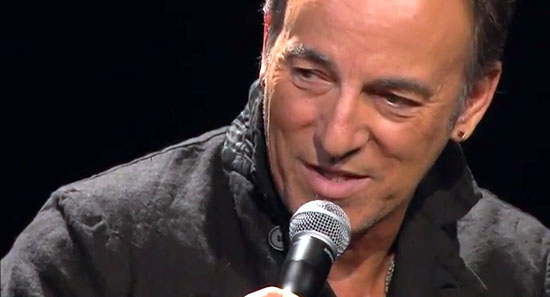

In mid-February, Bruce Springsteen appeared before international journalists in Paris to talk Wrecking Ball. At this Théatre Marigny press conference, he spent an hour fielding numerous questions about the new record, the psychology of anger, the state of America, Clarence Clemons, his autobiography, his falsetto, and much more. A brief video clip was quickly posted online to give us a taste of the conversation, and quotes have since appeared in various newspapers. Now that the entire record has streamed, we're pleased to be able present a transcript from that day.

Among the revelations here: Bruce was originally working on a gospel record before Wrecking Ball came together. "I spent on-and-off about a year on that one before I threw it out, which is something I do every once in a while," he said, later adding, "I wrote 30 or 40 songs before these songs."

This is the only published Springsteen interview about his new record to date, a great insight into Bruce's state of mind on Wrecking Ball as the March 6 release day approaches.

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s time for me to fulfill a lifetime dream, to share a stage with Bruce Springsteen. A few introductory questions about Wrecking Ball. I'm curious to know why you've changed your producer, after working with Brendan O'Brien for so many years, and I’d like to know more about the process of recording.

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s time for me to fulfill a lifetime dream, to share a stage with Bruce Springsteen. A few introductory questions about Wrecking Ball. I'm curious to know why you've changed your producer, after working with Brendan O'Brien for so many years, and I’d like to know more about the process of recording.

The guy who produced this record is a fellow named Ron Aniello. I assisted him, and Jon [Landau] executive produced. Ron had worked on a few of Patti [Scialfa]’s records previously, and I was actually working on another record before this record. I spent on-and-off about a year on that one before I threw it out, which is something I do every once in a while. He came in to help me finish that one, and as we went along, a few of the songs started to come up for this record; he had a lot of fresh ideas about the way the music could sound, and he had a large library of sounds — alternative and hip-hop elements — and we used quite a bit of different looping techniques. It was just a very different experience, really, with the two of us in the studio when we started out.

You were in your hometown in New Jersey for these recording sessions?

Yeah, we were in our own studio, and each one of the songs started off as kind of a folk song, with just me and the acoustic guitar. And then everything else got slipped on.

And you had special guests, like Tom Morello…

Tommy Morello from Rage Against the Machine, he came in and played the guitar on "This Depression" and on "Jack of all Trades." Patti and Soozie sang; Max plays on a cut; Clarence is on "Land of Hope and Dreams."

As we have all heard, it’s a very powerful record that could have been written by both a wise old dog and a very young, brilliant man. Would you say you write more strongly when you're pissed off?

You can never go wrong pissed off in rock 'n' roll. The first half of it, particularly, is very angry. The genesis of the record was after 2008, when we had the huge financial crisis in the States, and there was really no accountability for years and years. People lost their homes, and I had friends who were losing their homes, and nobody went to jail. Nobody was responsible. People lost enormous amounts of their net worth. Previous to Occupy Wall Street, there was no pushback: there was no movement, there was no voice that was saying just how outrageous — that a basic theft had occurred that struck at the heart of what the entire American idea was about. It was a complete disregard of history, of context, of community; it was all about "what can I get today." It was just an enormous fault line that cracked the American system wide open. And I think its repercussions are just beginning to really, really be felt.

So I think I wrote "We Take Care of Our Own" somewhere around 2009 or 2010, and I put it away in my book. And the idea behind that song was that’s what’s supposed to happen, but was not happening. My work has always been about judging the distance between American reality and the American dream — how far is that at any given moment. If you go back to the work that I did beginning certainly in the late ’70s, I’m always measuring that distance: how close are we, how far are we, how close are we? Everything from Darkness on the Edge of Town, The River, to Nebraska, Born in the U.S.A., The Ghost of Tom Joad, those are all records that were always taking the measure of that distance.

That song, “We Take Care of Our Own,” it asks the question that the rest of the record tries to answer. Which is, of course: Do we? Do we take care of our own? And we often don’t. We don’t provide an equal playing field for all our citizens. And at the same time, it doesn’t cede what would be patriotism or images like the flag to just the right. I claim those, as I’ve done in a lot of my work throughout the years. The rest of the record tries to answer the questions that come up in the last verse of that song: Where are the merciful hearts? Where is the work that I need? Where is the spirit that reigns over me? Where are the eyes that see? Those are the questions the rest of the record tries to answer and that are embedded in the question that the title of that song is, “We Take Care of Our Own.”

Concerning patriotism, aren’t you afraid that a song like this, “We Take Care of Our Own,” might be misunderstood like “Born in the U.S.A.”?

You can’t be afraid of those images. I mean, I write carefully and precisely, and I believe clearly. And then you put it out there, and people hear it, and then it’s up to them. And if you’re missing it, you’re not quite thinking hard enough; you know, you need to go back and take a second look sometimes. But I don’t want to cede those feelings to just the right side of the street. I don’t like to do that. Which is why my work is often claimed by different political groups, because there is a feeling of patriotism underneath. That’s something I’ve had in “Land of Hope and Dreams,” and in my best music. But at the same time, it’s a very critical, questioning, often angry sort of patriotism. That’s not something I’m prepared to give up for fear that somebody might simplify what I’m saying.

I have many questions, but I’m not supposed to be the only one to ask.

Okay. I know: how did I get this good looking? I can’t tell you. All right, next? [Laughs] Genes. Next?

[Moderator opens question to the floor]

On this record, you include songs that aren't exactly new, with “Land of Hope and Dreams” and “Wrecking Ball” having been performed before. But they fit in the moment, right?

“Wrecking Ball” seemed like a metaphor for what had occurred — it’s an image where something is destroyed to build something new, and it was also an image [suggesting] just the flat destruction of some fundamental American values and ideas that occurred over the past 30 years. It was a 30-year process of deregulation and different things that added up to the inequality that we’re experiencing in the States right now. So, it seemed like a good metaphor.

With “Land of Hope and Dreams,” I needed a song that was very spiritual, because the record moves from guys who are really very angry to guys who are angry but constructive. To me there’s always a spiritual element in that, and a religious element to some degree. Maybe that’s just my Catholic upbringing, but that’s how I write about it. So that song was big enough.

The trouble with a record, if you write a really big song at the beginning, the record demands to gain size as it goes along — or else you blew your wad at the top, my friend [laughs]. That’s why, how many records do you put on where it's like, hey, that first song!… That second song’s good… [snores]. You’re out by number seven or eight.

But on our records, I try to build them so there’s a question asked, and there are scenarios where those questions are played out. If you look at this record, there’s a question asked: Do we take care of our own? I don’t think so, a lot of times. So then there are scenarios where you meet the characters who have been impacted by the failure of those ideas and values. You get to the guy on “Easy Money,” he’s going out for a robbing spree — which is really just what’s occurred at the top of the pyramid. He’s imitating your guys on Wall Street the only way he knows how: I’m going out tonight for easy money.

If you trace it along, every song introduces you to a slightly different character. Then at the end, I’ve got to find some way to mend their stories together so it all makes sense to you. I’ve got to try to find some way not necessarily to answer the question that I asked, but to move the question forward, to move the ideas forward, to move forward in the search for a new day. “A new day” comes up a lot in the record, which is really just, okay, how do you move forward? I’m interested in that.

So the record has to build, and it has to expand emotionally and spiritually, and it’s also supposed to be throwing you a good time in the mix. You know, it’s got to sound good and play great. That’s always a challenge, but “Land of Hope and Dreams” was a song of such size and spiritual dimension that by the time the end of the record came around, it fit really well.

Also, those are voices from history and other sides of the grave. If you listen to the record, I use a lot of folk music. There’s some Civil War music. There’s gospel music. There are ’30s horns in “Jack of All Trades.” That’s the way I used the music — the idea was that the music was going to contextualize historically that this has happened before: it happened in the 1970s, it happened in the ’30s, it happened in the 1800s… it’s cyclical. Over, and over, and over, and over again. So I try to pick up some of the continuity and the historical resonance through the music.

In the past, you’ve committed yourself to play for presidential candidates, and of course the presidential election is coming up this year in the U.S. Are you planning to sing or do some concerts for Barack Obama?

I got into that sort of by accident. What it was, the Bush years were so horrific that you couldn’t just sit around. I never campaigned for a politician previous to John Kerry. But at that moment it was such a blatant disaster occurring at the top of government that you felt if you had any cachet whatsoever, you had to cash it in, because you couldn’t sit around and watch it. So I campaigned for John Kerry, and Obama last time — and I’m glad that I did — but I’m not a professional campaigner, and every four years I don’t think I’m gonna pick a guy and go out for him. I’d prefer to stay on the sidelines. I generally believe an artist is supposed to be the canary in the coalmine, and you’re better off with a certain distance from the seat of power.

In 2008, you came out very strongly for President Obama. Are you still in the same mood today?

I think he did a lot of good things: he kept GM alive, which was incredibly important to Detroit, Michigan. He got the healthcare law passed, though I wish there had been a public option and that it didn’t leave citizens the victims of the insurance companies. He killed Osama bin Laden, which I think was extremely important. He brought some sanity to the top level of government.

He’s more friendly to corporations than I thought he would be, and there aren't as many middle class or working class voices heard in the administration as I thought there would be. I would have liked to see more active job creation sooner than it came, and I’d like to have seen some of these foreclosures stopped or somehow mitigated. The banks have had some kind of a settlement, a partial settlement, but really, there’s a lot of people it’s not going to assist. I still support the president, but there are plenty of things — I thought Guantanamo would have been closed by now. On the other hand, we’re out of Iraq, and hopefully we’ll be out of Afghanistan soon.

So many people after 9/11, and so many people these past couple years, look to you for your interpretation of events. Does that make you feel any kind of a burden? That so many people care? Look at us: when we were waiting for you earlier, so many people care about what you think, and what you feel about what is happening in the world.

Actually, I’m terribly burdened, and at night when I’m sleeping in my big house, it’s killing me [laughs]. It’s a rough life, it’s a brutal life! The rock music business: brutal, brutal, brutal. Don’t believe what anybody tells you.

No, it’s a blessed life. And these are just things I’m interested in, and things I’ve been interested in having a conversation with my audience about.

No, it’s a blessed life. And these are just things I’m interested in, and things I’ve been interested in having a conversation with my audience about.

I enjoyed artists when I was young who tried to, one way or another, take on the world — for better or for worse — and who were involved in the events of the day as well as just entertaining people. I have a big audience: I have Democrats, I have plenty of Republicans, I have people who just come to dance and enjoy themselves, and people who are interested in the social aspects of what I’m writing about. And I’ve really just enjoyed it all.

So I just enjoy having that conversation. If I have something to say or if I can write a song about it at a given time, I do. And if I don’t, then I don’t. I write to process my own experiences. I always figured that if I do that for me, then I do that for you. You write for yourself initially, just trying to understand the world you live in. And if you do that well enough, then it projects to your audience. But I’m not in elective office where I have to come up with a plan every day. I don’t experience it as a burden. It’s not like that. It’s pretty much a charmed life, I would say, if you’re a musician. That’s why they call it playing.

On this record, more than ever, we have spiritual references, biblical quotes, things like that. Is it because you feel your own mortality now?

No, I think I just got completely brainwashed as a child with Catholicism. Once you’re in… it’s like that Al Pacino line, I keep trying to get out, they keep pulling me back! Once you’re a Catholic, you’re always a Catholic. You get involved in these things in your very, very formative years. I took religious education for the first eight years of school; I lived next to a church, a convent, a rectory, and the Catholic school. I saw every wedding, every funeral, every Mass. Your life was filled with the smell of incense and priests and nuns coming and going, so it’s given me a very active sense of spiritual life, and made it very difficult sexually, but that’s all right [laughs].

On another subject, could you say a few words about the transition from Clarence Clemons to Jake? There's a great portion of your eulogy where you say, “Clarence doesn’t leave the E Street Band when he dies. He leaves when we die.”

I met Clarence when I was 22. That’s my son’s age. I look at my son, and he’s still a child, you know? Twenty-two is… you’re just a kid. And I guess Clarence might have been 30 at the time, so it goes back to the beginning of my adult life. And we had a relationship that was, I would say, elemental, from the very beginning. It wasn’t about anything we necessarily said to one another, it was just about what happened when we got close. Something happened. It fired peoples’ imaginations; it fired my own imagination and my own dreams. It made me want to write songs for that saxophone sound.

Losing Clarence is like losing something elemental. It’s like losing the rain, or air. And that’s a part of life. The currents of life affect even the dream world of popular music; there’s no escape. And so that is just something that’s going to be missing.

We’re lucky in that we have people around: we have Eddie Manion, who had played with the Sessions Band, Southside Johnny, and our band previously; and Clarence’s brother had a son who, in 1988, came and saw his uncle play the saxophone. Clarence mentioned Jake to me quite a few years ago, and he was on the road with us a bit during the last tour, and he plays very well. He’s also been around the band and understands what our band is about. We were together with Clarence the week he passed away, and there’s a good musical and spiritual connection to Jake. So I’m excited about it. I think it’s going to add to the new conversation about these things that we’re going to have with the audience when we come out on stage.

I heard that you’re going to have a complete horn section on tour—it takes a full horn section to replace Clarence.

It does—it takes a village to replace the Big Man! It takes many men [laughs]! So, we’ll do the best we can.

Do you think it’s going to change something in your stage personality?

I don’t know. It will change everything a little bit — or a lot. The thrust of the music will still be what it is, but it’s a big loss. Any time you lose… you know, we lost Danny [Federici], and these are guys that you’ve been with for 35 or 40 years, and you just enjoyed them being there, you know? But you move on. Life doesn’t wait.

So Clarence has to be replaced, you replaced Max at a few concerts with his son…

Right. I’m working on replacing myself now, and I’m gonna stay home. I will be home, and somebody else can do it [laughs].

On the last tour, you paid tribute to Joe Strummer, and you showed some support for Gaslight Anthem, and it seems you're still a huge, huge music fan. I was wondering, as you look back at your music fandom, what four or five bands would you start and end with?

My own music fandom? Oh gosh… I hate to speak them aloud [laughs]. Because in truth, there were so many. I’d say one of the greatest things about music fandom is if you have one other person who is as fanatic about it as you are. That would be Steve [Van Zandt] for me. Steve and I have shared an insane and intense love affair with rock 'n' roll music since we were teenagers. If a guy changed the way he combed his hair, if they changed their outfits… pop is all about obsession with detail. It’s a world of symbolism, and you live and die by that sword, for better or worse. But it’s also a lot of fun, and fun to argue about and fun to debate about.

My own music fandom? Oh gosh… I hate to speak them aloud [laughs]. Because in truth, there were so many. I’d say one of the greatest things about music fandom is if you have one other person who is as fanatic about it as you are. That would be Steve [Van Zandt] for me. Steve and I have shared an insane and intense love affair with rock 'n' roll music since we were teenagers. If a guy changed the way he combed his hair, if they changed their outfits… pop is all about obsession with detail. It’s a world of symbolism, and you live and die by that sword, for better or worse. But it’s also a lot of fun, and fun to argue about and fun to debate about.

So one of the great things was my connection with Steve in that area, and also with Jon. Jon was another freak who just was — it was all about the music. That’s the most important thing. You’ve got to have a friend or a pal who is sort of alongside of you in your insanity and knowswhy you can spend three hours debating these things. I remember Steve and I on the bus to New York City, battling who was supreme at the time, Led Zeppelin or the Jeff Beck Group. Old Elvis, young Elvis. It goes on forever. It still goes on to this day. So that’s a great blessing. I wish all of you a good rock 'n' roll partner.

When you were younger, you could spend a full year agonizing about a drum sound in the studio. Now you release a record every two years.

Now I just agonize. It’s not over anything special [laughs]. That’s the adult. When you’re an adult, you don’t have to worry it as much…

Does that mean you're not trying to write "the great American novel,” with every record as one chapter?

Mainly, you’re trying to make a good record. You’re trying to make a record that won’t waste peoples’ time. You’re trying to be an honest broker with your fans — if I’m asking them to listen to it, I’ve got to know that it’s everything I have, at least at that moment. That’s why I think my relationship with my audience remains so vital and so present.

You’re always out there shooting for the moon, but in different ways. That hasn’t really changed. Our intentions on this album were no more nor less than our intentions on Born to Run or Nebraska. My intention is to do what, say, Bob Dylan did for me, which is to sort of kick open the door to your mind and your body, and make you want to move and think and experience and get angry and fall in love and reach for something higher than yourself and grovel around in something lower than that, also [laughs]. That’s the job description. That’s what people are paying you the money for: they’re paying you the money for something that can’t be bought. That’s the trick. And that’s what you’re supposed to deliver. You’re being paid for something that can’t be bought; it can only be manifested and shared. That’s when you’re doing a good job.

Can I ask you about anger? About the anger you might feel, the anger there seems to be so much of in America in the last four to five years, that anger that surfaced in the Tea Party… Does that anger get to you? And what do you see as its source?

I think our politics come out of psychology, whether we like to think so or not. And psychology, of course, comes out of your formative years. So my experience growing up — between when I was born to when I was 18, I grew up in a house where my mother was the primary breadwinner, and she worked very hard every day. My father struggled to find work, and I saw that it was deeply painful and created a crisis of masculinity, and that it was something that was irreparable at the end of the day.

I think our politics come out of psychology, whether we like to think so or not. And psychology, of course, comes out of your formative years. So my experience growing up — between when I was born to when I was 18, I grew up in a house where my mother was the primary breadwinner, and she worked very hard every day. My father struggled to find work, and I saw that it was deeply painful and created a crisis of masculinity, and that it was something that was irreparable at the end of the day.

Those conditions are present in the United States right now, where you have a service economy overtaking a manufacturing economy. You’ve got a lot of guys who worked in manufacturing whose jobs have disappeared, and who are not necessarily coming out of those manufacturing jobs with the skills to move into a service economy. It’s a very, very different world. And so you have quite a few homes where the man is no longer the primary breadwinner.

I think that the lack of work creates a loss of self. Work creates an enormous sense of self, as I saw in my mother. My mother was an inspiring, towering figure to me in the best possible way, and I picked up a lot of the way that I work from her. She was my working example: just steadfast, just relentless. But I also picked up a lot of the fallout. When your father doesn’t have those things, it results in a house that turns into quite a bit like a minefield. And it can be abusive in different ways — just tremendous emotional turmoil.

So, I kind of lost him, and I think a lot of the anger that surfaced in my music from day one comes out of that particular scene. And as I got older, I looked toward not just the psychological reasons in our house, but the social forces that played upon our home and made life more difficult. And that led me into a lot of the writing that I’ve done.

I’m motivated circumstantially by the events of the day: that’s unfair; that’s theft; that’s against what we believe in; that’s not what America is about. But the deepest motivation — and the reasons to ask those questions, ultimately — comes out of the house that I grew up in and the circumstances that were there, which is mirrored around the United States with the level of unemployment we have right now. It’s devastating. People have to work. The country should strive for full employment. It’s the single thing that brings a sense of self and self-esteem, and a sense of place, a sense of belonging.

There are times in the new songs when you come close to calling for an uprising. Can you really foresee that kind of response in America?

Well, the thing that has happened that’s good in the States: there’s no doubt that the Occupy Wall Street movement in the United States was powerful about changing the national conversation, which has been stuck for decades primarily coming from the right. The Tea Party set it for quite a while, and if you saw the initial years of the Obama presidency, he was kind of working under the national tone that the Tea Party set.

The minute Occupy Wall Street occurred, suddenly people were talking about economic inequality. No one has gotten anybody in the States to talk about economic inequality for the past two decades. You had politicians who tried — John Edwards tried with his “two Americas” — but they couldn’t get any traction. The labor movement wasn’t successful bringing that up as a current issue. But people in the street do it, and it works. It works. And if you look now, suddenly you’ve got Newt Gingrich calling Mitt Romney a vulture capitalist [laughs]. I mean, that’s impossible! That would never have occurred in ten million years without Occupy Wall Street. Where they go from here? I don’t know, and they’ve got to be careful; it’s a very delicate dance, and you don’t want to alienate the people who you’re speaking to. You can go off the edges with it. But it was without a doubt very important in changing the tenor of the national conversation. If you go to the United States right now, there's discussion about the one percent and the 99 percent; you have people talking about economic inequality, and what to do about that, for the first time in a very, very, very long time.

I'd like to talk about your version of American patriotism, which has always been inclusive and generalist: it doesn’t matter where you come from, you can get on the train. And then you look America and the way that the Tea Party is polarizing one side, and there are people who don’t even believe that Obama is an American. Do you think that the political system is actually irreparably damaged? Can you actually have a “United” States?

I don’t know. I think this is the issue: we’ve destroyed the idea of an equal playing field. They’ve had some recent studies that say, depending on where you come from, no, you can’t get on the train. There was a study recently that said that people were locked into the strata under which they were born. If you were born at the top, your chances for progress were great, and if you were born struggling, more often than not that’s where you were going to remain. So that’s a big promise that’s been broken.

There’s a critical mass point where a society collapses. You can’t have a civilization where the society is so factionalized — you just can’t have it. People have got to be connected; everyone’s welfare has got to be connected. So, that’s a huge, huge challenge. The unemployment level is dropping a little now, which is good, but it’s going to take a long time to even remotely get back to the employment level we were at just a few years ago. Is it irreparable? I don’t know the answer to your question.

I read somewhere that you were working on your autobiography. Is that true? And how's it going?

I wrote a little bit, and then I stopped for a couple of years. I haven’t looked at it in quite a while. It’s one of those things… I wrote a little bit at one time, but then I see in the newspaper that everybody else is writing them, and so you don’t want to be just another goldfish in a bowl. It’s like: hey, Pete Townsend! He’s got one coming! Neil Young! He’s got one coming.… ahhhh, fuck it, the hell with it [laughs].

What would you call it?

The… Handsomest Man in Show Business. [Laughs] No, I have no idea. My Story!... I Believe! I may call it that. According to Me. [Laughs]

I was just curious, how, throughout the years, throughout all your albums, how are you still keeping in touch with the public concern? I mean, practically, are you involved in your local community?

Well, there’s an idea that it would be hard to do, but I don’t think that it is; I think you can make it hard. We have organizations we’ve worked with for 25 or 30 years, in every city and also in my local area. But really, I think the answer to what you’re asking, and I get asked this a lot, is that you have to remain interested and awake. You have to remain alert. You have to be constantly listening—and interested in listening—to what’s going on every day. You have to remain interested in life and in the way the world’s moving. You have to be awake and listening—that would be the best way that I would put it.

Well, there’s an idea that it would be hard to do, but I don’t think that it is; I think you can make it hard. We have organizations we’ve worked with for 25 or 30 years, in every city and also in my local area. But really, I think the answer to what you’re asking, and I get asked this a lot, is that you have to remain interested and awake. You have to remain alert. You have to be constantly listening—and interested in listening—to what’s going on every day. You have to remain interested in life and in the way the world’s moving. You have to be awake and listening—that would be the best way that I would put it.

As a writer, the way that I write, it’s like you’re hungry for food. That’s the writing impulse. The writing impulse is the same as one for hunger or for sex — it’s like that. It’s not something that’s related to your commercial fortunes. I mean, I’d do it for free. I’m glad that they’re paying me, but it was something I did for free before they were paying me.

And so I’m constantly looking — the writer looks for something to push up against. Tom Stoppard, the playwright, once said he was envious of Vaclav Havel because he had so much to push up against, and he wrote so beautifully about it. I’d prefer to stay out of prison if I can, but I knew what he was talking about. You need something pushing, pushing back at you, and you tend to do your best work when there’s something that you can really, really push up against. And there has been in the States over the past — certainly for me, over the past 30 years, but that’s come to a head over the past four years now. So this record, there was quite a bit to write about.

I want to ask a question about your singing. You have a wide range now — you can go from a very high falsetto to a strong and deep voice. Do you feel you’re still improving?

[Sings falsetto:] Yes, I do! I do, I do, I do… [sings deep:] I do. [Laughs] For some reason when I got around 40, I was able to sing high all of a sudden. I’m not sure why. I used to have a harder time when I was younger; I have a little bit of a falsetto now that I didn’t have. Look at Tony Bennett: Tony Bennett’s 85 and he’s still singing. He still sings great. So I think you need a little bit of luck, and then you have to have something you’re dying to sing about.

Do you feel more powerful as a musician than you would be if you were a politician?

A politician? No, I could never be a politician. I just don’t have the skills. Everything that I’ve studied was about learning how to do my job as a musician better, and also trying to understand the arc of my own life and my family’s life — an immigrant family that came to the United States. I thought that there was something common in that, that if I understood that about me, I might be able to illuminate something about your life. That’s all I do. I have no interest in any other job, really, and I have no other skills whatsoever. So I’m hoping to continue to remain “powerful” as a musician [laughs] as best as I can.

I know you've spoken about Clarence a bit already, but I just wanted to ask, with respect to the actual making of this album, did the passing of Clarence have any effect on that?

Well, most of the record was made; 95 percent of it was made, and it wasn’t an E Street Band record. It was basically a solo project. So that didn’t immediately impact the record. This record took quite a different musical tilt. We were lucky to get him on “Land of Hope & Dreams,” which was essential —really essential. When he comes up, it’s just a lovely moment for me.

Two years ago, onstage in Glastonbury, you joined a small band from New Jersey called The Gaslight Anthem. Is it true that your sons make you listen to new bands?

Yeah! You know, music is a family business. Of course, you’re always concerned that your kids might… I mean, it’s what Mom and Dad do, how cool can it be? I always say, kids wouldn’t mind coming out to see 60,000 people boo you, but who wants to see 60,000 people cheer their parents? Nobody really wants to see that — I don’t care how great a kid you are, you don’t want to see that. Booing, that’s interesting.

But he ended up with tremendous musical taste and a great musical appetite, and he just began, “Hey Dad, come here. Check it out.” So I actually heard a lot of music that way: Gaslight Anthem, Dropkick Murphy’s, Bad Religion, Against Me!… a lot of young musicians through his guidance. I’ve gone to quite a few shows with him, and we’ve had some great times, so it’s a nice thing to share.

I want to ask about your songwriting process. Do you set aside time each day to write? And can you talk about how inspiration comes?

I don’t set aside any time in the day. I write when the fire gets lit, and then I do it in spare time. I work at home, so there’s always something going on — somebody needs to be picked up from school, somebody needs to be dropped off at school. But it doesn’t take me long, like it used to. These songs were all written… “We Take Care of Our Own,” “Shackled and Drawn,” and “Rocky Ground” came along for almost a gospel album package I was thinking about. And then the other things came very quickly, one after another, as soon as I found the voice that I was going to use. “Easy Money,” and then the rest of the songs came pretty quickly, one day at a time.

The main thing writing is about, a lot of it is waiting. You may wait a year to write something good. So you have to be pretty good at waiting. And I may write a lot in the meantime — I wrote 30 or 40 songs before these songs, just to sort of keep everything going.

The inspiration thing, if that’s what you’d call it, it’s like a visitation. Something happens where suddenly, it’s like the planets aligning: the times, what’s in the air, what’s inside of you, there’s your craft, your skills… and suddenly they go click. And zoom. If they don't align, nothing happens. When it clicks — when the times, you, your story, the story that is alive out there at the moment, what’s going on in the world, your craft, your skills align like that — then bang, it comes out, and then good things happen. Hopefully. You sort of wait for that moment a lot.

One last question. Should they ever start filming The Sopranos again, would you join Stevie in that? What would be a part for you?

I have no acting skills whatsoever. This is all the acting I can do, and I’m doing it right now. So you see, it would be very dull. But Steve, on the other hand, is naturally hilarious, as he has been since the day I met him. He was quite a natural. I’m going to stick to music for now.

Before we go, just a personal favor… can you do that falsetto again?

I’m not gonna be as good as Obama. Obama can sing. Did you see that? [Sings falsetto:] “Let’s stay together.” I can’t do it. [Laughs]. He’s better than me!