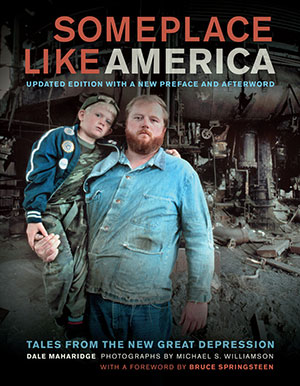

YOU MAY KNOW THEM as the guys who inspired "Youngstown" and "The New Timer," journalist Dale Maharidge and photojournalist Michael Williamson. When Springsteen sat down with their book Journey to Nowhere in 1995, he found those missing pieces of the puzzle for his album The Ghost of Tom Joad. Maharide and Williamson's Pulitzer Prize-winning work together continues to this day, documenting America's "new underclass," and Springsteen continues to follow it, too, writing the foreword for their latest book, Someplace Like America: Tales From the New Great Depression.

YOU MAY KNOW THEM as the guys who inspired "Youngstown" and "The New Timer," journalist Dale Maharidge and photojournalist Michael Williamson. When Springsteen sat down with their book Journey to Nowhere in 1995, he found those missing pieces of the puzzle for his album The Ghost of Tom Joad. Maharide and Williamson's Pulitzer Prize-winning work together continues to this day, documenting America's "new underclass," and Springsteen continues to follow it, too, writing the foreword for their latest book, Someplace Like America: Tales From the New Great Depression.

George Packer recently wrote in the New Yorker, "Someplace Like America is unrelenting prose... There's something doggedly heroic in this commitment to one of journalism's least glamorous, least remunerative subjects."

When Someplace Like America came out in 2011, we hosted Dale and Michael's video blog, "The Road to Someplace Like America," showing in words and images the backstory behind their work together, riding the rails, picking up where James Agee and Walker Evans left off.

At the time, we promised one more piece: to bring their story up to the present, tracing how their mid-'90s meetings with Springsteen put their "asses back on the story," and the impact of Bruce's influence, both before and after the Joad era. We're proud to present that story now from Dale and Michael, as Someplace Like America has just been published in paperback. This updated edition, also with the Foreword by Bruce Springsteen, has a new Preface and Afterword, "Letter From the Apocalypse," reported in Detroit [above]. Both the 2011 hardcover and 2013 softcover editions are available from Backstreet Records.

READ ON for the rest of the story of Dale, Michael, and Bruce... and don't forget Sweet Jenny.

By Dale Maharidge

Photographs by Michael S. Williamson

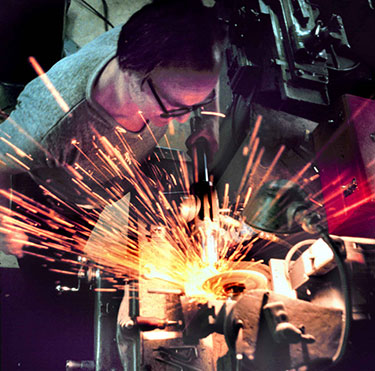

MY FATHER WAS A STEELWORKER at Cleveland Twist Drill, the nation's premier industrial cutting tool company. He also ran a side business in our basement, resharpening these same kinds of tools on machines, some which weighed over one ton. [At right: Steve Maharide] Dad often worked down there 'til 11 p.m. With each cut that showered orange sparks over dad's shoulder, the heating ducts delivered a burst of steel smoke to the bedroom I shared with my brother. I grew up breathing steel dust.

MY FATHER WAS A STEELWORKER at Cleveland Twist Drill, the nation's premier industrial cutting tool company. He also ran a side business in our basement, resharpening these same kinds of tools on machines, some which weighed over one ton. [At right: Steve Maharide] Dad often worked down there 'til 11 p.m. With each cut that showered orange sparks over dad's shoulder, the heating ducts delivered a burst of steel smoke to the bedroom I shared with my brother. I grew up breathing steel dust.

In 1968, at age of 12, Dad taught me how to grind. I worked with him. In the 1970s I also took a job at Plastic Fabrication, Inc. where I operated a rickety World War II-era lathe on which I machined, within a tolerance of a few thousandths of an inch, 60 nylon bearing spacers per hour. I put in long days grinding tools and cutting spacers.

On Friday evenings I'd pop a Stroh's, then another, on the way to a good beer drunk. I'd lie sprawled on the living room floor at 6 p.m. blasting WMMS-FM from waist-tall speakers to hear Murray Saul's "get down" tribute to the weekend, a primal rant directed at people specifically like me laboring in factories. It was followed by the station's now-legendary playing of a pre-release cut of Bruce Springsteen's "Born to Run."

I confess that I resented the station's hyping of Springsteen as the blue-collar troubadour. I didn't want to be reminded that I was blue collar. I was a regular at the famed Agora nightclub. But when Springsteen played for a $4.50 cover charge, I wouldn't ride my motorcycle downtown to hear him.

I wanted to be a writer. After being fired from "Plastic Fab" (I was told that I had a "bad attitude"), I began freelancing for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, grinding tools for my father and delivering them to smoking factories between working on stories and being a commuter student at Cleveland State University.

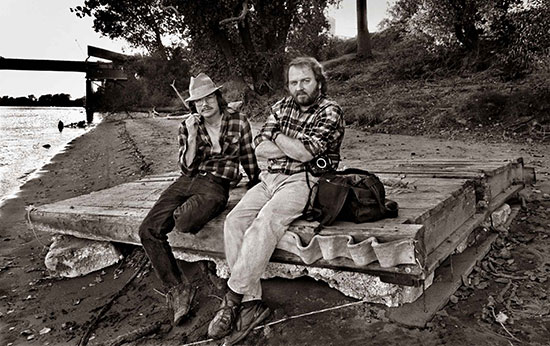

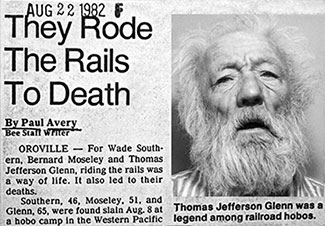

By 1980, armed with a portfolio of clips but lacking a college degree, I drove my Datsun pickup west. I lived out of the truck as I sought a job at a California newspaper. I felt the flames of the steel mills licking at my ass. Could I really write my way out of factory work? Many nights, as I camped among other homeless people, I had grave doubt. But after three months, I was hired on at the Sacramento Bee. That's where I met photographer Michael S. Williamson, and we began documenting people living on the margins. [Above: Dale and Michael set out riding the rails in 1982] In 1985, this led to the publication of Journey to Nowhere: The Saga of the New Underclass, our book about downsized workers in Youngstown, Ohio and other workers who became hobos.

Amid this, I bought all of Springsteen's albums. I became a born-again fan. (Enough time had passed, and I was no longer a self-loathing blue collar guy.) His music spoke to the kinds of people Michael and I were meeting.

When Springsteen's Born in the U.S.A. tour came to northern California, I wrangled the assignment to write the news story for the Bee. On September 18, 1985, I arrived early at the Oakland Coliseum. I didn't have any special access, and I didn't want it. I'm uncomfortable around celebrity. I was drawn to the long-time fans. They resented the newbies attracted by Springsteen's arena stardom — "the same kind who go to see Michael Jackson," one tailgating man told me.

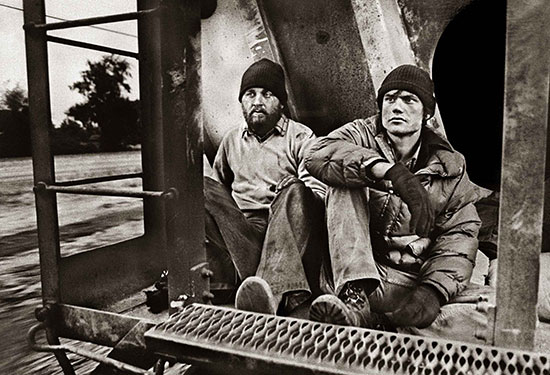

I continued reporting from the nosebleed seats with the diehard fans. I wrote in the Bee about Springsteen: "Between songs, he talked about unemployed steelworkers in Youngstown, Ohio, who have been 'left on the dock of the American dream.'" I was pleased that he was aware of what had happened to Youngstown. [Above: Ken Platt Sr. and Jr. at the Jenny Blast Furnace in 1984]

I continued reporting from the nosebleed seats with the diehard fans. I wrote in the Bee about Springsteen: "Between songs, he talked about unemployed steelworkers in Youngstown, Ohio, who have been 'left on the dock of the American dream.'" I was pleased that he was aware of what had happened to Youngstown. [Above: Ken Platt Sr. and Jr. at the Jenny Blast Furnace in 1984]

The 1980s were rough on Michael and me. We produced two more books on poverty, covered the war in El Salvador, the revolution in the Philippines, and many other difficult projects. I later wrote in a New York Times story: "If I showed up at your door in those days, your life had been marked by epic tragedy. It's no exaggeration to say that in writing for newspapers and books I closely witnessed 1,000 shattered lives, which is to say I retain 1,000 demons from that decade."

I quit the newspaper in 1991 and ended up hiding out from those demons on the bucolic campus of Stanford University where I had a visiting teaching gig. I spent late nights strolling the campus silent except for the tsking of irrigation sprinklers watering the Canary Island palms spangled against the stars. What was I? I was certainly no longer blue collar. But inside I didn’t feel white collar. Though I loved teaching, I felt out of place.

Michael withdrew to the mid-South to teach. He was broke. He printed the final project in our trilogy of books on workers and poverty researched in the 1980s, The Last Great American Hobo, in a shack behind the cottage in which he lived. He couldn't afford heat and water froze in his developing trays. Once he phoned while working and his teeth chattered.

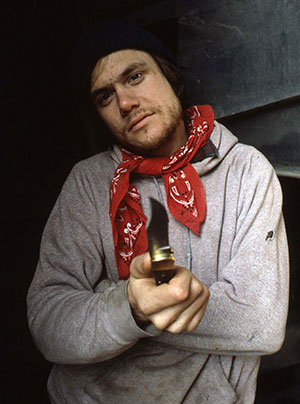

Not long after, our 1980s books rated inclusion in Contemporary Authors, the biographical library reference series on writers. On September 6, 1995, I sent off an essay to the editors. In part, I wrote, "All I know is that each book took a chunk out of our lives. One sets out to educate Americans about poverty in the hope that in some small way conditions will be changed. Then comes the realization that Americans don't seem to care. This, along with the horror of the lives one documents, takes a toll. I can't speak for Michael, but I plan to never again write a non-fiction book about poverty." [Left: Dale in 1983, on two days of no sleep and in a "hairy" part of town]

Not long after, our 1980s books rated inclusion in Contemporary Authors, the biographical library reference series on writers. On September 6, 1995, I sent off an essay to the editors. In part, I wrote, "All I know is that each book took a chunk out of our lives. One sets out to educate Americans about poverty in the hope that in some small way conditions will be changed. Then comes the realization that Americans don't seem to care. This, along with the horror of the lives one documents, takes a toll. I can't speak for Michael, but I plan to never again write a non-fiction book about poverty." [Left: Dale in 1983, on two days of no sleep and in a "hairy" part of town]

By that time Michael and I hadn’t seen each other in almost two years. Our phone chats were infrequent. We shunned the emotional toll of our 1980s and we each were the biggest reminders of that history. The Washington Post had recruited him, and he was named "Photographer of the Year," a national award that meant a seven-city tour, the last stop in Sacramento. I called Michael and told him that we had to slap some of our 1980s demons into submission.

On October 20, 1995, we went to the hobo jungle on the Sacramento River [below]. We drank beer and unloaded — among the many troublesome things, we talked about No Thumbs, the old hobo from our first book who had been murdered. We both hate the psychobabble word "closure." We certainly didn't have that. But we ended that night with a better understanding of all that we'd witnessed.

Michael had learned that morning that his wife, Michelle, was pregnant with Sophia, their first child. He was going to take a week off to photograph the California places when he was an orphan and foster kid, including where his mother was killed in Los Angeles when he was 11, to create a journal for Sophia.

I drove two hours home to Stanford. The next morning I awakened to a message on my answering machine from Sandy Choron, who worked for Bruce Springsteen.

I drove two hours home to Stanford. The next morning I awakened to a message on my answering machine from Sandy Choron, who worked for Bruce Springsteen.

When I phoned back, Sandy said Springsteen wanted to meet us when he performed at Neil Young's upcoming Bridge School Benefit Concert. Springsteen had been inspired by Journey to Nowhere to write some songs, but she was vague about which and how many. I phoned Michael. When I got him to believe me, he re-arranged his schedule.

On October 27, we went to the Shoreline Amphitheater in Mountain View, California where we went backstage and met Springsteen's managers, Barbara Carr and Jon Landau, then had dinner with Wavy Gravy, the emcee for the night; he emceed the 1969 Woodstock festival. Michael once spent a night in a jail cell with Wavy, after he got caught up in the cops arresting protesters at the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, but Wavy didn't remember that.

Springsteen performed two songs from The Ghost of Tom Joad. As he came offstage toward us, Neil Young was slapping him on the back. A door opened behind. A woman flew out and slammed into me with such force that I was nearly knocked over. It was Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders. She was next on. We shook hands with Bruce and Neil, then Bruce invited us into his dressing room.

"So how the fuck did you hear about our book?" I asked, the first words out of my mouth.

"I bought it when it came out," Bruce said.

Bruce offered whiskey. He wondered why Journey was long out of print — he said it should be available. I asked Bruce if he'd be willing to write an introduction if we could get the book re-released.

"Sure," he said.

We spent another half hour with Bruce and then talked with Terry Magovern, his assistant. We didn't think to ask about more specifics. We wouldn't learn for weeks that Bruce was inspired by our book to write two tracks on The Ghost of Tom Joad, "Youngstown," and "New Timer," the former partly about steelworker Joe Marshall and his son in Youngstown, the latter partly about No Thumbs [right], the old hobo who was murdered and inspired the character of Frank.

We spent another half hour with Bruce and then talked with Terry Magovern, his assistant. We didn't think to ask about more specifics. We wouldn't learn for weeks that Bruce was inspired by our book to write two tracks on The Ghost of Tom Joad, "Youngstown," and "New Timer," the former partly about steelworker Joe Marshall and his son in Youngstown, the latter partly about No Thumbs [right], the old hobo who was murdered and inspired the character of Frank.

We drove back to the Stanford campus at the hour when the sprinklers were tsking. We couldn't just reissue that book — we'd have to update it. Otherwise it would seem dated. That meant re-immersing in our den of demons. But how could we not? Bruce contacting us the very morning after our reunion to put to rest those Journey to Nowhere days was surely a message from the cosmos if there ever was one in our lives.

It meant we were not supposed to be done with this work.

Logistics were a problem. I was a year behind delivery on a different book, and I had classes to teach; Michael had the Washington Post job. We hatched a plan where with the Thanksgiving holiday working for us and playing hooky from our jobs, we could carve out 11 days, not much time for driving across the nation and interviewing people. But it was the best we could do.

Our agent, Gloria Loomis, went to publishers. It came down to two. We were warned that one could be difficult. But we had a preexisting issue with the other publisher and chose the potentially troublesome one. We flew to Cleveland on November 17, 1995 and began the intense trip.

The warning about the mercurial publisher proved prescient. He turned venomous through no fault of anything we did. It's a long and depressing story, and I will just tell this much: he made us give back a big part of the modest advance on a specious technicality, and when the book came out, the publicists falsely told reporters that we weren't granting interviews. Bruce was chatting about us when he introduced "Youngstown" on the tour, and there was a lot of press. (We would talk with anyone!) It was the first anti-publicity campaign I’d ever encountered.

The warning about the mercurial publisher proved prescient. He turned venomous through no fault of anything we did. It's a long and depressing story, and I will just tell this much: he made us give back a big part of the modest advance on a specious technicality, and when the book came out, the publicists falsely told reporters that we weren't granting interviews. Bruce was chatting about us when he introduced "Youngstown" on the tour, and there was a lot of press. (We would talk with anyone!) It was the first anti-publicity campaign I’d ever encountered.

The publisher never really distributed the book in stores — in those pre-Internet sales days, we only sold some 200 copies. It's the rarest edition of all our books.

You can allow such things to consume you, or you can move on. There are two things that really matter:

One, Bruce got our asses back on the story.

Two, he got what happened to Youngstown out to a wide audience.

I'd told my Stanford students a few weeks before the phone call from Sandy Choron that you never know who reads your work. Your job is to put the work out there. Period. It must exist and if you are lucky, it will impact others — you may never really know who it inspires. When Bruce later did the rock version of "Youngstown" with the E Street Band, recorded on the Live in New York City release, most listeners didn't know the genesis of the material. Some friends thought this would bother us, but quite the contrary. Because of Bruce, the story we told in Journey reached millions of people it otherwise wouldn't have touched. Getting the story out — that is what it's all about.

Those first few times we met with Bruce, I confess to not being wholly comfortable due to my unease around celebrity. Bruce did nothing to foster this, he was a gem — it was my issue. My awkwardness with this finally melted in early 1996 when Bruce played in Youngstown. He wanted to visit the ruins of the Jenny blast furnace that is the subject of the song.

Bruce, Michael and I had to sneak in a back way through deep snow to avoid getting arrested by guards — a story I tell in Someplace Like America: Tales from the New Great Depression — and in the hour-and-a-half that we spent in the dead mill, we worried about how American workers have been trashed. At that moment, we were just three guys talking about the terrible things happening to our country and the power of story.

Even though we've since met with Bruce numerous times, I don't think he understands how much influence is a two-way street. When I listen to "Youngstown," it still makes me emotional. Bruce condensed some 10,000 of my words, and Michael's many pictures, into a song of 299 words, capturing the soul of what happened to those ravaged steelworkers.

And the influence continues. Because Bruce got as back on the story, we carried our 30 years of work forward in Someplace Like America: Tales from the New Great Depression, which has just been released in paperback. A few years ago we went back and found some of the homeless people and blue-collar workers from Journey and the early 1980s and tell the saga of others today. Once again, Bruce wrote a foreword to this new book, for which we are grateful.

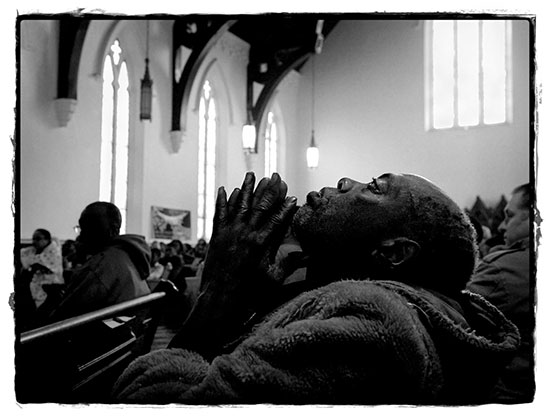

Wrecking Ball came out just a few weeks before we were in Detroit for ten days last year, to update Someplace with an afterword. It was music to match the ravaged city. Michael and I have now been documenting workers together for 33 years. Not only is "Youngstown" and "New Timer" infused in our new book in both the words and pictures; they and other of Bruce's songs were in our heads as we worked.

I think back to lying on the floor in Cleveland in the mid-1970s listening to "Born to Run." Michael in that period had ended up in a great foster home, in high school track and winning running awards; his team used to practice to that song. Was it the Fates weighing in or just pure blind randomness that we would eventually connect with Bruce?

- photographs by Michael S. Williamson

- additional images courtesy of Dale Maharidge

Purchase Someplace Like America:

Tales From the New Great Depression

Hardcover - Softcove

See more of the book's backstory on Dale & Michael's

video blog, The Road to Someplace Like America