Thom Zimny and Bruce Springsteen, November 2019 - photograph by Rob DeMartin

Bruce Springsteen needs a shooter — and so Thom Zimny's list of credits as a filmmaker gets longer all the time.

Following initial work as an editor on Live in New York City, Zimny has gone on to helm film projects of all kinds for Springsteen, from music videos to full concerts, both new and archival. Trained as a documentarian, Zimny also maintains the film archive for Thrill Hill; he puts it to good use as the go-to guy for anything in Bossworld that requires a moving image — that is, when he's not working with Bruce on something entirely new, like short films for "Hunter of Invisible Game" and "A Night With the Jersey Devil." And though Thom has expanded his purview in recent years, directing acclaimed documentaries on Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, his 20-year relationship with Springsteen remains at the center of his life's work.

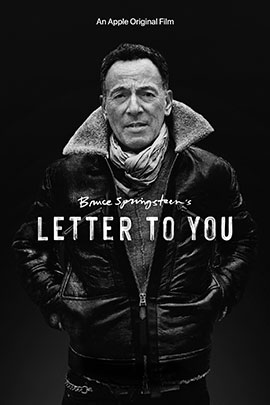

Zimny has directed seven feature-length Springsteen documentary films, utilizing both new and archival footage: Wings For Wheels: The Making of Born to Run (2005), The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town (2010), Darkness on the Edge of Town, Paramount Theatre, Asbury Park (2010), The Ties That Bind (2015), Springsteen on Broadway (2018), Western Stars (2019), and now the new album companion film Letter to You (2020).

The last of these, an Apple Original (given a surprise early release on October 22), documents Springsteen's 2019 recording session with the E Street Band, a whirlwind affair that resulted in a new album in just five days (or four days, plus one to listen, as the story goes).

The last of these, an Apple Original (given a surprise early release on October 22), documents Springsteen's 2019 recording session with the E Street Band, a whirlwind affair that resulted in a new album in just five days (or four days, plus one to listen, as the story goes).

Like Western Stars, which Springsteen co-directed, the Letter to You film incorporates new commentary from Bruce, whose voiceover gives context to the songs, extends their themes, and once again turns musical performance into something even more expansive — a "tone poem," in Bruce's parlance. Zimny's vision creates beauty out of the combined elements in the edit. But the foundation of the project alone — going inside the studio, to watch the E Street Band make new music — is enough to capture any fan's attention.

Zimny spoke with Backstreets editor Christopher Phillips shortly before the film's release, to explore the process from its initial spark — sitting around a fire with the Boss, the Beatles on the radio — to the final toast.

CP: The big question everybody gets asked is, what have you been doing with yourself during lockdown? "What did you do during the pandemic?" So I'm wondering: was Letter to You your pandemic project?

TZ: This was the pandemic project. Gratefully, we had finished filming. I had organized the footage and started to "sketch" a little bit, and then this thing arrived that shut us down completely — shut us down in the sense of a film production office. So I cut the movie at home, using FaceTime with Bruce. He would send me ideas by phone, and we made the movie back-and-forth that way.

So much of the creation of Western Stars involved you and Bruce working in the same space, running from one edit bay to the other; did Zoom or FaceTime help enable that, or were you more on your own for this one?

This was definitely different than the collaboration on Western Stars. I was on my own directing it more, in the sense that we couldn't be in the studio, but I did keep that dialogue very close. We were talking every day, we were texting, he was sending ideas for voiceovers, I was sending him things a ton as I started to sketch.… and really, the collaboration was strong on this.

Of all the Bruce movies you've put together, you've really never made the same one twice. Letter to You is centered around songs, but it's not a concert film; it has elements of Western Stars, but it's also showing us something that hasn't happened in decades. You couldn't have made this movie before.

Right. Bruce's work has been a huge influence on me, in the area of editing and also the idea of never repeating yourself. Never repeating yourself is an important mantra to me as a filmmaker.

With Letter to You I had the opportunity to try to revisit an idea that I started to chase when I was a kid, which is: What happens in the studio with the E Street Band? You know, at 16, flipping over the sleeve of The River and seeing a photograph of Jon [Landau] and Bruce at the board — that was the start of wondering about their creative process, about how it must feel to be in the room when one of these songs is created. So I took the opportunity, after 20 years of working with Bruce, to let that 16-year-old come back to the room.

I was able to capture a dream come true: to be in the room when he's demoing the band tracks, working with the full band. I'm looking across the studio, and I'm seeing gestures that reflect the archival footage I've spent so much time with — like, archival footage of Jon and Bruce together in 1978 — and I'm looking at the footage now and getting in the moment and I see these same guys.

There is a beauty in those details, of Jon and Bruce working together, being behind the board, the E Street Band talking…. These are relationships that are so powerful and strong, and you can see that secret silent language of gesture and expression that really conveys their creative process. When they start scribbling on notepads, a few letters and chords, and they have a 30-second discussion about a song they've never heard before and then sit down and this energy explodes.… the camera took it all in. So as a filmmaker, this was a completely different experience, a completely new film.

Springsteen on Broadway gave me certain challenges, capturing the theater in his live performance of the Broadway show; Western Stars was a whole other set of challenges: how do you go beyond making a concert film? But with Letter to You it was about capturing these things that you can't really put into words: the magic of E Street in the studio. New material. The power of the band just sitting around and then crashing into this space. This explosive drum sound of Max [Weinberg]. Seeing Steven [Van Zandt], in the span of 30 seconds, come up with an idea that he's conveying to Bruce, and all of a sudden the song is different and opened up. Or hearing Bruce go back to lyrics from the '70s, and earlier songs that I knew from scratchy bootlegs are now being sung in the studio. All this was magical to capture and film.

And what I really wanted to do is remain invisible. I had three cameras there — the filmmaking wasn't a presence to take over the studio. I really wanted to keep ourselves as invisible as possible. So there was no huge crew stationed anywhere around, there weren't people milling around; this was a recording of a record, and I was invited into the space to see what would happen.

That seems like a difficult thing to pull off, considering the "observer effect" and the way that just your presence there could alter things. How do you make that happen? How do you put on the invisibility cloak?

Partly by being "Thom," who's been around for 20 years. Who's been there for soundchecks. Who doesn't really approach it as "I'm here to be a director"; I'm just Thom in the room. And really, it's that these guys are here to make a record; I have a job and a mission to capture it, but I'm not there to get in the way or announce my presence.

Plus, I had my cinematographer Joe DeSalvo and a lot of the camera operators that worked with me on Springsteen on Broadway and Western Stars. So I had these people who were in tune to the work ethic and the environment of the space and knew how to keep out of the way.

A lot of it does come down to relationships, and history. In the past 20 years I've had some great friendships and assistance in making the films. Barbara Carr really makes things happen — she's given me so much support and so many opportunities over the years; together with Jon, that's an amazing production team I'm lucky enough to have.

And then on the studio side, there are people like Kevin Buell and Rob Lebret, and of course Ron [Aniello], who really have helped me and welcomed me into the space of the studio. And that really comes back specifically to the invisibility cloak: they're great at guiding me as to what's going on, what will be possibly happening, and helping me get this footage in a way that I can remain invisible.

But the big thing is, I don't stop something from happening. I'm not there to direct a scene and come up with an idea, or to ask someone to do something again.

You're documenting.

Yeah. It's documenting in the purest way, because you have to be ready to jump as high as you can. All of a sudden Bruce is saying, "I'm going to do these songs," and you're at a place where batteries need to be changed, or these cameras have issues… things happen, and you just don't stop rolling. You just keep going.

The band was that way in recording. There's a certain energy with this material, an energy in the room, and I just tried to jump on board — because this thing was strong and moving fast, and I was just hoping the gods were going to throw me some magical moments.

As a filmmaker I was seeing things unfold — like the collaboration of Ron and Bruce, or the beauty of Roy [Bittan] figuring out a part — and all of a sudden you go, "Oh my god, that's E Street!" There's the power of the instruments themselves, like seeing Danny [Federici]'s old glockenspiel, or even a case that had the name "Clarence" on it, and that's where the sax was sitting. Some beautiful moments in which you see the full history of this band, and I really tried to stay in that zone and capture it.

One thing that struck me is the warm feeling of being inside this studio. Especially contrasted with the snow and the winter weather outside. Even in black and white, when we move from outside to inside, it really feels like you're coming in by the fire — that warmth really comes through.

The light in the studio became this metaphor for me. I really like space, and space is a character to look at in each one of these films. In this case, the studio itself is a beautiful, magical place, much like the barn [in Western Stars]. It has a presence. And I looked at the light that would pour into the studio as this sort of healing power.

When I first talked to Bruce [about this new material], he told me about "Last Man Standing," and then in one of the sessions that I filmed, I heard "House of a Thousand Guitars." And the House of a Thousand Guitars became the studio in my mind. The studio is blessed with both the present and the past, and this creative energy, and light — the light spilling into that studio, and the use of black and white — became this metaphor for me.

What moved you to shoot in black and white?

That decision came from a conversation I had with Bruce. He called me to the house on a Sunday and said, "Hey, come on by." So I sat with him, and he made an outside fire. And he said, "Listen, during this week the band's going to come together. Why don't you come over and film it?" I said, "Great!" He said, "Yeah, it's going to be all new material; I got this song 'Last Man Standing,' and it kind of has some references to George [Theiss] and the Castiles… I think it'd be great to see if you can get anything that week." And then we just sat and we listened to music.

What were you listening to, do you remember?

British Invasion, bands of that era. I remember the Beatles playing, just on a small speaker on the side of the table. And there's a gray sky, and a small fire going, and we're listening to the Beatles, and the light felt a certain way… and I remember thinking about black and white in that moment.

Then I went to the studio, early morning, shortly after that conversation, and I walked around and I found a keyboard that had the sunlight pouring through it. Danny's notes were on the keyboard from the Born in the U.S.A. tour. And I remember thinking that the history of this band is amongst this arrangement of guitars and amps.

I had gotten Bruce a guitar for a present, which he plays in the film; it's an early Sears & Roebuck guitar, and he actually ended up talking about it in the film. So that was sitting around. You could see a lot of the history of the band, and also the history of him playing in bands and coming through the clubs. I remember that light pouring over those instruments and thinking this would be really powerful in black and white.

And of course the outdoor imagery is powerful in black-and-white, too — all those stark snowscapes. I'm wondering what prompted that, who took the drone shots, that kind of thing… as well as, how metaphorical would you say it is?

The first day of shooting Bruce got a text from Pam [Springsteen], and he said, "It's snowing! It's snowing out." It was a small snowfall, and the snow became something in that moment for me. It became a visual reference. My cinematographer Joe DeSalvo — who's been with me for 25 years and is an amazing guy — helped shoot this imagery of snow and landscapes that could really bring out the scenes I thought of when Bruce was narrating, as well as the lyrics of Letter to You.

So it evolved that way. This simple moment of Bruce saying, "It's snowing out" — it's an example of the little things you chase. And there's a beauty with the snow and that sort of imagery, but there's also this reflective tone that I thought played into what I was hearing when they were recording. I try not to think about it too much, but I work off of what the narrative of these songs are evoking, the feeling. I don't try to match the lyrics. I try to just live in the space of these songs. And I also think that I just step into a place where a lot of this stuff happens unconsciously, and I'm just grateful that it's worked for Bruce.

Knowing how you work, I was wondering what the "Elvis's bicycle" of this movie might be. And it occurred to me as I was watching: maybe it's the weather. Maybe it's the snow.

Every film, I try to figure out: what am I being drawn to that I can't really explain but it feels important enough to chase? And yeah, with the Elvis [Presley: The Searcher] film it was Elvis's bike, and with this movie it was the deep connection of studio light, the healing power of light, and then also the fierce beauty of snow itself. And how that gives you a sense of both being in the present but also the past.

Its power in black and white is so striking, visually, that the trees themselves took on an otherworldly feel. The roots and the trees from above and that point of view of a drone really played into a lot of what I would say is a sense of "higher power" or spirituality — because this is an enormously spiritual record, the lyrics and the themes. I tried to lean into that with visuals that didn't interrupt or signal directly; I tried not to land too squarely on the words themselves or the ideas presented. I worked with the feelings.

Those themes are even more present in Bruce's narration.

Right. Bruce talking about the songs, what they mean, and what inspired them, that's a crucial part of the film. It was so important in helping me find the tone — along with the power of the score by Ron and Bruce.

I'd love to know more about the score — I've been curious since seeing the score credit at the end of the move — is that material lifted from some of the tracking of the album? Or is it completely different material?

I think Ron and Bruce scored each individual piece, and those are all new compositions — there may be some references to track, but everything is uniquely designed. The power of the narration and the sonic quality of the score really drove the film to a certain tonal place.

- photograph by Rob DeMartin

You've got Bruce meditating on mortality, in between so much joy and life in the studio… I can see that being a tricky thing to balance.

And even me — I had to look at my relationship of working with Bruce and think about it as something that's… not forever. When he talks about his own death, it's a really powerful moment in the voiceover, and it's something that I had to step up to as a filmmaker. This idea of the band not being forever, and Bruce, too — that was highly emotional at times to work on.

If you look at the world at that moment, when I'm making the film, a lot of these questions and themes that are presented within Letter to You felt very pressing. The music was written way before the virus and the general scenario we're in right now, but the themes are very relevant to what we were experiencing while editing the film — which was the shutdown of everything.

Right. And that's a painful irony in the film: they are so clearly ready to go on tour. They're toasting to that future they've planned, talking about Italy and San Siro…

It's extremely bittersweet. To watch the band play these songs, get so excited about what they're recording, and then start talking about the road. It's hard to hear, but in one of Bruce's toasts, he says, "Here's to the road!"

When I made the "Ghosts" video with Bruce, I said to him, "Let's take the band symbolically out on the road." That's why I included a lot of rare outtakes and footage — including actual footage from the Italian concerts — because we're all just missing the live environment of E Street. And the doc does show exactly where everyone was going at that moment with the power of this music, which was the drive to share it with fans in concert. It's a beautiful energy, but it can be a little hard to think about now.

I'm wondering how you craft this whole thing — how do you take five days and turn it into a movie? How much of that vision came during the shoot versus during the edit, and was it easy or difficult to figure out what you wanted to show of this five-day stretch?

It's never easy to figure out what's going to go in the film. You have this constant conversation with yourself — and also a constant conversation with Bruce and Jon. But Letter to You was a unique thing, because it was deep in the edit. I was reliving those five days with the E Street Band recording, and I really did want to hone in on smaller moments. I knew I wanted to show things that as a fan I would love to witness: the guys meeting each other in the morning, or just little moments of pure musical discovery.

And I also wanted to show when things don't work: when something's too loud, or there's confusion. At times there are these moments of limited dialogue, and you go, "Man, have these guys known this song forever? Bruce just taught them!" And then there are these other moments where people are overlapping, they're jumping over each other, they're talking and trying to sort it out.

There are also moments of Bruce and Steven, for example, reflecting their deep connection in rock history.

I love getting to see those two putting their heads together in the studio, working out ideas together — it's the kind of thing we've heard about for years but never really seen.

When Steven and Bruce go to the mixing board and discuss — in the middle of a playback — hand claps, and then start clapping to the track, and then go to harmony… I see two guys who have this amazing collaboration and friendship, but I also see the history of rock right in that one moment. The history of the British Invasion. And this shorthand, this secret language, could be missed if you just plowed through the footage. So I really looked at it and watched it in real time, taking in all the details and catching where something conveys what I consider a story point that needs to be brought forward. That mainly tended to be the spontaneity of the studio, the spontaneity of Bruce and the band during these sessions.

Thinking about the 16-year-old you, I'm interested in your perspective on all of this both as a filmmaker and as a fan who got to be present for this thing that we've always pictured in our heads. There's what we always imagined things looking like in the studio, versus what you actually witnessed. As a fan, what surprised you?

Something that surprised me was how much these guys reflected an energy, a tone, that was just like the archival footage I've seen of them back in 1978. The musicality of people's voices, Steven talking to Bruce, Garry [Tallemt] just holding his bass a certain way… there was a familiarity to a lot of these small, tiny details. And for me as a fan, there were these great moments captured in the film that tie the two eras together — like when Roy walks up and just hits a few notes on the glock, and then you have the presence of Danny. Charlie [Giordano]'s playing is just so amazing to hear, too, and a lot of those are the original keyboards that Danny had used.

But what really surprised me, which I feel like comes across in the film, was that magic that you can't really put into words: when something is now an E Street Band song, a Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band song, and the magic of it going from Bruce demoing it just twice to the band, and then the band performing it five minutes later. And you hear the DNA of E Street. It's just shocking.

That's the biggest thing. The new material itself was so inspirational for me as a filmmaker, along with the power of witnessing the E Street Band drive it forward.

It was also amazing how quickly Ron Aniello and Rob Lebret got the sound — how that was captured so that in first playback you heard, you got a very clear feeling of the power of the song. After working on the Darkness on the Edge of Town doc, where I went through many stories of trying to get a drum sound, or a certain sonic texture, and how long it took for them to get that sound — with Born to Run, too — this was an amazing experience in that the masters were able to just jump in and go to it.

Along those lines, I'm curious about what we don't see. In other words, was there a day before the band came in where Ron and the engineers worked to get the sound right? Is there anything left on the cutting room floor, or that you weren't there for? Or at this point is it that Bruce's home studio is already good to go, these guys know what they're doing, and "let's go"?

Well, the studio was prepared days before, and there was some minor tweaking on day one, but overall people just walked in and started to work.

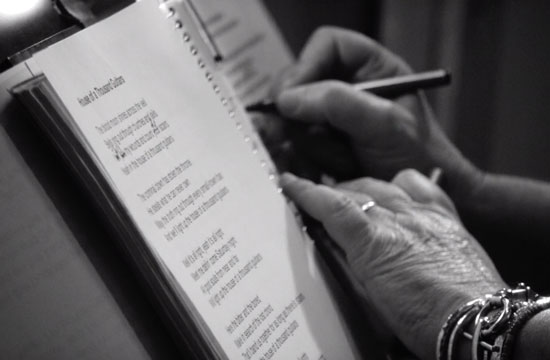

We'd heard in advance that Bruce taught the new songs to the band on guitar, rather than recording demos in advance, and to get to see that in action is fascinating. Watching them watching him, with their notebooks, and learning in real time. I think it's on"Ghosts" where you catch Max subtly air drumming, working things out in his head, as Bruce is showing them all how the songs go.

Right, it's fascinating to see these guys scribble a secret language — Max especially, just these little marks. I'm not a musician, but I love the intensity and the focus that's found in the footage when you look at their eyes. If they're going to do background claps, they're going to get it right. There's no detail that's not taken in, in a real way.

We've only really talked about the new album shoot, but you also use a great deal of old film in Letter to You, which is really moving and well-incorporated. And tantalizing, in terms of the live concert footage.

I know I'm criticized for holding back things. I don't think that's the case. I just really try to find and use things that were not shown in the other docs, and many of these things are recent discoveries.

There's some of Bruce very young and performing that has recently been restored that I've included in the doc, and there are some wonderful, small moments of 16mm No Nukes footage that's really beautiful. Clarence carrying Bruce off the stage! These moments are sometimes lost in time, because they're very quick, one-off, a matter of seconds. They're not full songs. It's a camera capturing something that gets lost at the end of a reel — that's what the shot is of Clarence.

There's some footage restored from the Bottom Line, and I recently put that into a video; so I'm always exploring what's available, while trying to keep within the narrative of what the film's about — finding the right archive so that it drives the story forward. And with Letter to You I was able to go deep in the vault.

What else did you use besides No Nukes and Bottom Line? There was some early stuff with [David] Sancious in there, and I was trying to figure out what that was.

It's footage from a college show — Nassau College. And some other early footage was unseen Gaslight [Club, NYC].

The shot of the boy and the girl running through the snow towards the camera, is that Bruce? It was hard to tell whether that's family footage or something else.

It's not Bruce — but it looks like it could be.

And then is that footage from the Upstage? It's all over the "Ghosts" video, too — some of us have gone back and forth on where it's from.

It's not Upstage — but again, it sure feels like it. It has all the elements of it.

I don't want to spoil any magician's tricks or anything!

Oh, that's okay — it's not Upstage, but it was such a great reference. The paintings on the wall, the way the kids are dancing.… it really captures the feel of that club and that environment. Early bar bands.

I was glad to see Jon Landau in the film; since he's not technically producing these days, I wondered what his involvement during the recording might be, whether he'd be in the studio at all. And there's such a moving moment toward the end, as he listens to "I'll See You in My Dreams" — I was really struck by that.

That was a moment that I saw unfold. I'm able to talk to my cameramen — I'm situated in a different part of the space, but I'm able to whisper into the ears of the cameramen. They had these earpieces so that they can hear me. And on "I'll See You in My Dreams," I could see that one camera had picked up Jon getting emotional. That was during a playback, and it was completely a spontaneous, real moment — and one of my favorite moments, because it showed the power of this collaboration and this friendship over all these years. It happened so quickly — I think I was just lucky that everyone was there to get it. I was grateful that it unfolded that way, in such a pure way.

It feels like a key moment for sure. And I'm curious about Landau's involvement all around — I know that you guys talk a lot about the work you do, share references, and I'm wondering how he factored in, both in the sessions and in the film.

Jon Landau's relationship with Bruce, to me, is such an inspirational force to be around for the past 20 years. I have such great respect for the E Street Band, but I also have great respect for these two guys who've really given me the most magical thing that a filmmaker could ask for, which is trust and opportunity to grow. They took me as an editor working on Live in New York and have given me the chance to be with the band in the room.

So when I saw Jon at the mixing board, I knew right then and there that that was another element that I wanted to capture. Besides the story of making this record, and the story of the E Street Band, I wanted to convey the beauty of this friendship that I see. I wanted to get across the closeness that they've had through the years, and the power that they hold in the studio together.

For me, that sequence of Jon hearing the playback was something that was enormously satisfying to capture — Jon listening so intently and being emotionally drawn into it, to such a great degree. I knew I had a film that had to build to that moment.

The first time I saw that scene, I sent it to Bruce. I waited a long time before I sent it to Jon, but it was an amazing, pure moment of honesty, and it also reflected something I was chasing, which is the power and the love that I have witnessed in the friendship and collaboration that these two guys have.

For me as a filmmaker, Jon has been an enormous influence, and my dialogue with him extends past just my work with Bruce. I had him as a producer on the Elvis doc, and he was a great creative powerhouse there; with Letter to You, he gave me this opportunity to run really far with it. He was very supportive of the ideas that I was bringing, but he also just gave me those simple things: time and trust. An opportunity to expand on the language of making these films, expand on ways to shoot it. I carry both these guys in my heart in the creative process, because as Bruce might say, it is a conversation that we've been having in film for 20 years.

How would you say that conversation has progressed, over the past few films you've made?

With Springsteen on Broadway, Jon was really involved with me on that. With Western Stars it was a little less — it was more Bruce. This one was a completely different experience where I turned to them in a different way.

In each case I've used the opportunities to have dialogues with them, and grow and learn as a filmmaker. And also as a person — I consider Jon a close friend. I also have to say the same for Barbara Carr, who's a producer again on Letter to You; she brings so many things together so that the film can be made in a certain way. You really feel the power and the force of them wanting this to be the best, and that has been something that I've leaned on for the last 20 years. Those relationships are essential.

When you say you "turned to them in a different way" for this one, can you expand on that, tell me what that means? I'm interested in how the collaborative aspect changes from one film to another.

For every one of these films, the relationship of working with Jon and Bruce has been different. Each one of these I go into without expectation, and they organically come together. With Western Stars I was much more in a direct dialogue with Bruce. We made it together in the edit room. With Letter to You I turned to both Bruce and Jon at different times for different influences and conversations. So in some ways I feel like this was one where I was sharing ideas with them differently, and they were open to that, and I was asking them different questions.

In this case, I guess I was turning to both these guys in a way that allowed me to present some new ideas of capturing these smaller moments. Sometimes I would just say, "This is interesting from the point of view of the fan." Because I can step out of it differently. That is my role.

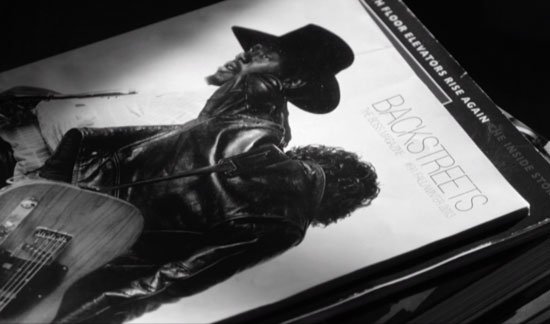

From the fan POV, I have to say, a big cheer went up at my house when Backstreets magazine showed up on the screen! My favorite Easter egg for sure.

You got it. That's the shot! That was a present. [Laughs]

Thank you — it felt like a hug from you.

It totally was. Backstreets has been a big part of my life, as a longtime fan, I can't believe I didn't bring it up right away when we started talking — it's a thank you for many years of friendship and support, for being part of my education and journey, and it was a deliberate shout-out.

But it was also a real documentation — that magazine was in the studio, and I wanted to include it because it was a perfect visual reference, when Bruce is talking about the idea of a conversation with old fans and new fans, too. I love seeing it in the sunlight like that.

I do too [laughs]. I could hardly believe my eyes. You made us all very happy. And there is so much here in general that feels like a gift to fans, that could easily have been left out of the story. I love the playbacks. Performing the songs is one thing, but then watching them as they listen and hear different things, that's fascinating — and a lot of movies would leave it out.

I really wanted to let that 16-year-old kid have that moment of going, "Look at these guys work. Oh my god!" So I'm letting things unfold. And because I was able to film every single take… I think it's really important to know, I had sync for all the takes. So I was able to really document exactly how that record was recorded.

Somebody told me that there's word going around that there were 30 cameras in the room. But no, there were three cameras in the room — and at one point, one fixed camera, which was used like one or two times in the whole movie. Essentially there were three cameras in the room. It was a quiet affair. This wasn't 30 people. Somebody said 30, and Max jokingly said 20, but the reality of it is that we were really guests, and I hoped to find the cameras captured this thing that has intrigued me since I first got my records from Bruce back in '79.

The big "story" of this record seems to be that it's the E Street Band recording together in the studio for the first time since the early '80s, which itself is a wonderful thing to get on film. But you also get across how they just came in there and: bang, bang, bang. As Stevie says, "Three hours a song. That's how the Beatles did it!" And that was a remarkable thing to me.

Is that really what it was? Did Bruce really have the record figured out ahead of time and they just came in and did it? Were there outtakes or discoveries along the way? Or was it just, "I've got a vision, let's go do it, four or five days, we're done"?

The film reflects exactly the process that happened for the making of the record. The guys came in, and by the fourth day they had so much of the record done. I heard playbacks and mixes in the moment that just reflected what the songs were. So what you get is these craftsmen at the height of their powers. They walked in — they weren't searching for a drum sound — they walked in ready to go to that place of E Street. I just had to have my cameras ready and capture it.

I didn't know it was going to be that way. I didn't know how it was going to go. But right away, hearing the first playback, I was like, "My god, this is the song!" So that energy, and the power of that, is witnessed in making the film and the power of that lives sonically on the album. If you really want to know what the studio was like to make this album, it's there in the film.

If I didn't know any better, I might think this was weeks of work compressed into 90 minutes, instead of days.

This is a Masters Class captured. These guys just are at this place of playing so powerfully. Max was just amazing to film, the strength of his drums. And the sonic qualities of the E Street Band at this point are really amazing to get on film, because there's an intensity and focus — it comes across on the camera, and it blows your mind that they can just start playing something that I know they just heard four minutes ago.

"Burnin' Train" was such an uplifting surprise at the end. I thought the film was winding down, and then "Burnin' Train" — which is sequenced much earlier on the record — comes along and lifts me up. Was that the intent in closing with it?

I think "Burnin' Train" became the end track one afternoon when I was with Bruce — actually, we were FaceTiming. I had told him how much I loved to see the band play that opening riff, the power of it, but I also said it feels like it takes you "off." It was just a conversation I had with him, and I don't remember exactly how we got there, but it was the kind of thing… the moment we made that cut, it was the end of the film. It took you to that place. I remember him doing the vocal on that, and Max on drums is just stupendous — so it's a powerful track, and it seemed like the perfect ending of the movie because it does take you to another place. And that other place is a place of healing, after a lot of very deep thoughts and emotions in the narration, as well as Jon's sequence where he breaks down during the playback. So it felt very cathartic to have "Burnin' Train" take you up.

What was behind the decision to leave out two songs, "Rainmaker" and "Janey Needs a Shooter"? Had the movie just gotten too long, or were there other considerations?

I think the film talks to you [during the edit], and you try to listen to it. You listened to its tempo, and it was telling you it was not the time to open it up further. Like you had reached a certain place of ideas and emotions. It points to both the beauty and the difficulty of editing: making the very hard decision to not include your favorite track — for me, "Janey."

It wasn't a big discussion, but at the same time we were trying to stay truthful to what the film was telling us. And the film was telling me we've reached our place, we need to move on.

Incorporating the ritual of the toasts after a hard day's work was a nice touch. Did you get some shots of tequila along the way?

Oh, yeah. [Laughs] It's a great tradition. It's amazing to see — that embrace of everyone at the end of the day. It's a beautiful thing to have witnessed and be part of.