Bruce Springsteen, by his own admission, is no stranger to finding inspiration in the music he loves. As a songwriter, it's one of the aces up his sleeve. There's the Wall of Sound production of "Born to Run," the Suicide-esque "State Trooper," homages to Chuck Berry, the Raspberries, and the Beach Boys. Nods to the Drifters, Smokey Robinson, Van Morrison, Roy Orbison, The Animals... heck, like it or not, the guy was a "new Dylan" at one time. Don't forget Gary U.S. Bonds (what was "Sherry Darling" if not Bruce's stab at his own "Quarter to Three"?) and Elvis Presley ("Fire" says it all). "Man's Job" is such an effective Sam & Dave-style number, Bruce even got Sam Moore to sing it with him. While other artists attempting this trick may rarely go beyond pastiche, Springsteen manages to make it all… Springsteenian.

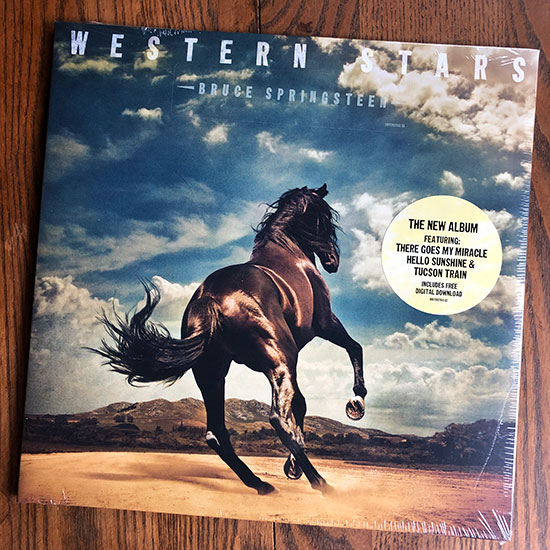

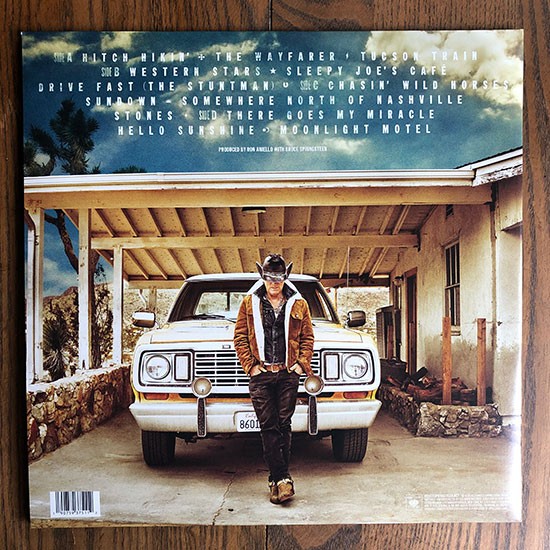

Western Stars, the inspired solo album that's long been Bruce's worst-kept secret (both he and Jon Landau have teased it in the press for years), sustains that trick for its entire running time. Springsteen and co-producer/multi-instrumentalist Ron Aniello return with the material that brought them together in the first place: a project with origins earlier in the decade, but set aside to pursue a line of writing that became 2012's Wrecking Ball. Through a succession of distractions — 2014's High Hopes, the 2016 River Tour, a little endeavor called Springsteen on Broadway — Western Stars sat and waited its turn. As successful a collection of songs as anything since Magic, as cohesive and thematically unified as Wrecking Ball, the time is right for the stellar Western Stars to have its moment in the sun.

When the album was announced in April as "drawing inspiration in part from the Southern California pop records of the late '60s and early '70s," some might not have known whether to anticipate a Laurel Canyon vibe, the Beach Boys, or the Fifth Dimension. If you'd been paying attention, Springsteen was more specific about just what part of the West Coast scene he was thinking of in a 2017 Variety interview: "Glen Campbell, Jimmy Webb, Burt Bacharach, those kinds of records. I don't know if people will hear those influences, but that was what I had in my mind. It gave me something to hook an album around; it gave me some inspiration to write."

To narrow the field further, there's a particular breed of song popularized in the late '60s and early 1970s, by Webb and others, that supplied the biggest transfusion to what runs through the heart of Western Stars. Think of Webb's "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" and "Wichita Lineman," Paul Williams' "Waking Up Alone," John Hartford's "Gentle on My Mind." And not just out of California: contemporaries were Kris Kristofferson's "Sunday Morning Comin' Down," Jim Croce's "I Got a Name," Neil Diamond's "Solitary Man," even Bobby Goldsboro's "I'm a Drifter." While Springsteen in the early '70s was focusing on Boardwalk trysts and gangs of wizard imps on various New York City cross streets, these songs were about men movin' down the highway, men who were very much alone.

Call it independence or isolation, solitude or self-reliance, it's the themes of those songs — musicality aside, though obviously Western Stars does share instrumentation in spades — that resonate most with Springsteen's newest collection. Men With No Name, drifters, ramblers, men who are leaving, men who've been left.… these are the characters who populate Western Stars. As Tunnel of Love was a song cycle about love and commitment, this one is the flipside: a meditation on desolation, sun-bleached and seasoned by Springsteen's "lasting love affair with the desert." It's a lonely record.

There's hardly a relationship on Western Stars that lasts longer than a car ride — in fact, the greatest amount of human connection you'll find is on the opening track, as a hitchhiker gladly heads down the road apiece. It's a series of encounters with characters that might as well be imported from previous Springsteen songs: a young expecting couple, a trucker, a hotrodder eager to blow 'em all out of their seats. The hitchhiker is "high on top of the world" in that trucker's cab, "a rolling stone just rolling on," as carefree as it gets.

Next up, "The Wayfarer" doubles down on the theme and even nods knowingly at how well-trod this path is: "Same old cliché, a wanderer on his way, slippin' from town to town," Springsteen sings. But already, that devil-may-care feeling has given way to white-line fever, and there's clearly a life — and a love — the Wayfarer has left behind.

From here on, we have stories of lonely men and love lost. Harkening to songs like "Reno" and "Dry Lightning," romances are only recalled in the form of hazy reveries and regrets. There are no Marys, Marias, Mary Lous, Wendys, Cynthias, or Janeys; the only women with proper names, May and Sally, are married to other men, mentioned only in passing. If there's a relationship at all in these 51 minutes, it's in "Stones" — and that one is so riddled by deceit there's not much else left. By the end of the record, the affair in "Moonlight Motel" is such a faded thing of the past it might as well be a ghost story.

What these characters do have — well, those who aren't complete drifters — is work.

Like many Springsteen characters before them, not only is their identity and self-worth tied up in the cross of their calling, vocations are often so specific you might crack a smile. In a line that's up there with "I'm a sergeant out of Perrineville, barracks number 8," or "I work for the county out on 95," our man in Tucson makes sure we know he has his crane operator's license. A few are in the entertainment business, like the songwriter of "Somewhere North of Nashville" and the sub-titular character in "Drive Fast (The Stuntman)." The latter fights through the pain and scars of his gig enough that you'll think immediately of Springsteen's soundtrack song "The Wrestler." Pins in his ankle, a cracked collarbone, a steel rod in his leg… what is it, for Bruce, about these guys who beat up their bodies for others' entertainment and keep on going? Ask the man who spent decades jumping off pianos and knee-sliding across the stage.

In "Sleepy Joe's Café," the singer's trade isn't clear, but we know he's got the kind of working week that requires a place to blow off steam come Friday night, much as in "Working on the Highway," "All That Heaven Will Allow," and "Out in the Street." In "Chasin' Wild Horses," the title is not only a metaphor but also what this guy gets paid to do. We don't get details about his lost love, but we do know he's a contract worker in Montana for the Bureau of Land Management.

Like that county lineman in Wichita, all this feels mostly like lonely work, with plenty of space for feelings to echo around. Jimmy Webb told the BBC that "Wichita Lineman" sprang from an image he retained from childhood, spying a lone repairman at the top of a telephone pole in the Oklahoma panhandle. "I thought, I wonder if I can write something about that? A blue collar, everyman guy we all see everywhere — working on the railroad or working on the telephone wires or digging holes in the street. I just tried to take an ordinary guy and open him up and say, 'Look, there's this great soul, and there's this great aching, and this great loneliness inside this person, and we're all like that. We all have this capacity for these huge feelings.'"

That's precisely what Springsteen seems to be going for on Western Stars. In these stories of men going it alone, Bruce doesn't look away from the cost of isolation — that's the entire raison d'être of lead single "Hello Sunshine," which is a straight admission of the price, the lure, and the wish to overcome it, after years of battling depression. But Springsteen still clearly finds depths, dignity, and plenty to admire in the solitary man. The instrumentation is often what conveys that POV. Springsteen comes right out and says he's "always had a sweet spot for the rain," and in the music that accompanies these stories, he can't help but romanticize the loneliness. When the horns and strings swell, as they often do, they evoke nothing as much as a heroic lone rider, looking out over a vast plain, in full CinemaScope.

photograph by Danny Clinch

Springsteen describes Western Stars as "cinematic," and you can take him literally. That quality lies not just in the expansive, widescreen feel of the production in general, but in musical cues that directly evoke Western picture soundtracks. To describe the particular orchestral sound Springsteen has crafted here, that dominates the record, you don't necessarily need to call up Countrypolitan, the Nashville Sound, or Aaron Copland (who producer Aniello namechecked along the way). It's often as simple as this: cowboy movies. As a friend described the album after an initial listen, "It's like his next Broadway show is a Western, and Clint Eastwood directed."

If an artist's job is "to get your audience to care about your obsessions" — as director Martin Scorcese said and Springsteen is fond of recounting — this album is a reminder that Bruce's obsessions go beyond girls and cars, and he's leaning hard on the Western in Western Stars. We know about Bruce's fondness for John Ford pictures, especially John Wayne in The Searchers — standing in the doorway but unable to bring himself to come inside, he'd be right at home on this album. Then there are early Springsteen songs like "Evacuation of the West" (featuring cowboys, rough riders, outlaws, and desperados), even a favorite childhood book, Brave Cowboy Bill, which helped inspire "Outlaw Pete." You feel it most in the music, the sound of those strings and horns evoking sun-streaked vistas of the American West and — remember all the movies? — the archetypal heroic horserider. These musical moments recall Western soundtrack themes, Spaghetti and otherwise, like "Once Upon a Time in the West" — a composition Springsteen loves so much he not only used it as introduction music over the years, he even recorded his own version of it for 2005's We All Love Ennio Morricone album. That recording combined symphonic strings and horns with Springsteen's guitar, surely a guiding star pointing the way to this new album.

Gestures toward the Western become full-blown on the title track. The album's masterstroke, "Western Stars" is the crown jewel of what Springsteen described as "a jewel box of a record." Our protagonist is literally a Western star — well, if not a star, exactly, he's certainly done his time in cowboy pictures, took a bullet from The Duke as a claim to fame, and is still making a living on the set (even if he's currently shilling for Viagra). "Western Stars" marries a stirring melody with haunting lap steel and a slice-of-life lyric, capturing the wistful thoughts of an aging actor hanging in there in modern-day Hollywood. It's another spot in the country where the sand turns to gold, and when that soundtrack orchestration surges, you might even think this guy got himself a piece of it.

"Western Stars" hammers home the double-meaning of the album title — not just the stars in the sky (or a Tennyson reference, if you want to get highfalutin' about it), but the stars on the screen. It's a triple meaning, if you consider California stars of 1960s and '70s AM radio. In addition to Webb, Campbell, Bacharach and the rest, you may also hear shades of Tom Waits — the young, clearer-voiced Southern Californian singer/songwriter heard on his first Asylum album, Closing Time — especially in the sing-song melody of "Hitch Hikin'." Scott Walker and the Walker Brothers are in there, too; as we previously noted, "Hello Sunshine" is Walker's "Sunshine" through the looking glass. In the end, part of the record's brilliance is its fusion of these different Western stars, the soundtrack composers and the '70s singers, to create a unique sound evocative of both at once.

photograph by Danny Clinch

For all its symphonic flourishes, the album's sonic trump card is the reveal of Springsteen's "big" voice, blowing the whole fucking place apart on "Sundown" and "There Goes My Miracle." It's vocal prowess that can stand up to Bacharachian bombast for sure, and if you'd just heard the quiet drawl of "Somewhere North of Nashville" you might not have thought Bruce had it in him. Concertgoers have heard it, though — Springsteen's ability to practically open up his chest to rise above the din and match the energy in the room, however large. It's remarkable to hear it in the studio, paired with music that calls for that kind of majesty.

With moments like these still likely to make a listener's jaw drop on his 19th studio album, you've got to hand it to Springsteen for never making the same record twice. There's some shared DNA with his previous solo outings, but Western Stars is a new, unified vision of a completely different aesthetic — a color Polaroid to the stark black-and-white of Nebraska or the daguerreotype of Devils & Dust.

That said, early buzz suggested this album sounded like nothing else Bruce Springsteen had ever done. That would be overstating it. The E Street Band sound has been string-heavy since The Rising, with Soozie Tyrell's addition to the proceedings, and a song like "Lonesome Day" is a notable antecedent here. (Tyrell shows up on background vocals for three songs, but she only plays fiddle on one; violins are mostly handled by the Avatar Strings and Stone Hill Strings). Familiar sounds abound: a baritone guitar recalls Tunnel of Love, and that big '60s pop sound is one Springsteen first experimented with on Magic ("Girls in Their Summer Clothes" being another sweeping portrait of loneliness) and to a greater degree on Working on a Dream. "Sleepy Joe's Café" feels like the "Mary's Place" of the album, as a requisite "happy party" song — you could practically sense it coming from the song title alone. Still, you can imagine the Sessions Band tearing it up for a live highlight, and indeed the track features Charlie Giordano on accordion as well as Sessions Band horn players.

Lyrical concerns, too, mark this as a Springsteen joint — especially the push/pull between yearning for connection and going it alone, walking out on the wire versus finding a home. There are specific lyrical echoes from earlier works, like the ever-reliable "Last night I dreamed…," and even just recognizable, trademark cadences. (Fun game: sing "Reason to Believe" to the tune of "Western Stars." Mix-and-match with "Devils & Dust" and "All That Heaven Will Allow.") "Sleepy Joe's" could easily be a little café we know so well from "Rosalita" — San Bernardino isn't so far from San Diego, in the scheme of things. "Tucson Train" is the most Springsteenian all around, one track it's easy to imagine in the regular E Street rotation. Despite its ambiguous, uncertain ending (a quality it shares, intriguingly, with so many songs on the album), it's also one of the most hopeful, as a "Back in Your Arms" story with what feels like a real shot at redemption in the key line: "I'll wait on God's creation / Just to show her a man can change."

It's always tempting to find parallels between Springsteen and his characters. The guy who was "born to run," on the "outside looking in," searching for "the ties that bind"… he's present and accounted for. Considering Bruce's frank discussion of his own personal issues over the years, mental health and otherwise, a song like "Hello Sunshine" can be heard as remarkable self-analysis, a distillation of his struggles with isolation and depression. When he sings "if I could just turn off my brain" in "Tucson Train," it's easy to feel as much sympathy for the songwriter as for the character. But Springsteen himself feels just as present in the title track, a rider in the whirlwind who keeps putting butts in seats after all these years, glad his boots are still on. Stirring and sturdy, both modern and nostalgic, Western Stars has him shining bright yet again. Somebody get that man two raw eggs and a shot.

Order Western Stars compact disc

+ exclusive Springsteen bandana

Order Western Stars 2-record set

+ exclusive Springsteen bandana