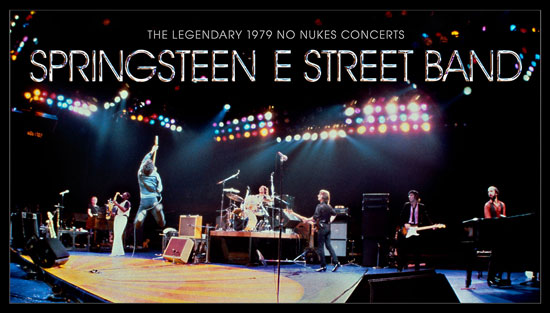

The release of The Legendary 1979 No Nukes Concerts captures Bruce Springsteen at one of the peaks of his stage powers, documenting some of the most exhilarating rock 'n' roll ever put on film. When it comes to the concerts' cause, and the efforts of Musicians United for Safe Energy, Springsteen is usually credited with little more than a "cautious toe-dip" into the waters of social consciousness. He famously chose not to write a statement for the concert program, and November's release did little to connect any activism dots under the surface of the rock 'n' roll show. But it's clear that Springsteen was not unmoved at the time by the dangers of nuclear energy. Events that occurred in 1979, coupled with two nights of playing on a bill with seasoned activists at Madison Square Garden, had a profound effect that we can now see with the vantage of time, shaping the sense of purpose, call to activism, and social responsibility Springsteen has demonstrated in the four decades since. The ramifications have been enormous, judging by his writing, his politics, and the large number of causes he has gone on to support. Looking back to the spring of that year, a glimmer of that future came with the release of another film — one that foreshadowed an imminent catastrophe.

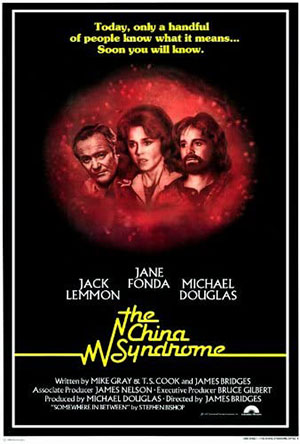

When Columbia Pictures released The China Syndrome in March 1979 starring Michael Douglas, Jane Fonda, and Jack Lemmon, its producers couldn't have known how connected it would become to current events. In an early scene, with the film's television reporters (played by Fonda and Douglas) inside a nuclear reactor control room, the entire reactor starts violently shaking in what we learn is an accident and harbinger of things to come. When someone describes the possibility of a reactor melting down to its core, it is said that such an event could "render an area the size of Pennsylvania uninhabitable." When Columbia Pictures released The China Syndrome in March 1979 starring Michael Douglas, Jane Fonda, and Jack Lemmon, its producers couldn't have known how connected it would become to current events. In an early scene, with the film's television reporters (played by Fonda and Douglas) inside a nuclear reactor control room, the entire reactor starts violently shaking in what we learn is an accident and harbinger of things to come. When someone describes the possibility of a reactor melting down to its core, it is said that such an event could "render an area the size of Pennsylvania uninhabitable."

Only 12 days after The China Syndrome opened, a real-life nuclear accident happened in Pennsylvania, the most significant accident in United States history. The release of radioactive gasses and radioactive iodine from the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant near Middletown, PA, were caused by its partial meltdown on March 28, 1979. President Jimmy Carter, himself trained in nuclear engineering, visited the plant. The film's stars stayed off of television interviews to avoid the appearance of exploitation.

It was only days later when Bruce Springsteen recorded his angry new song "Roulette" in response to the events. It was the first song put down on tape when Springsteen kicked off sessions for his fifth album, the follow-up to Darkness on the Edge of Town. The sonic fury of "Roulette,'' with its kinetic energy and frenetic barreling drums, matched the subject matter and the fallout (no pun intended) on its characters, whose lives are being gambled by the powers that be. It was a song destined for its times — or so one might have thought.

Bob Clearmountain mixed "Roulette" in two days and, as he reflected in Brian Hiatt's book Bruce Springsteen: The Story Behind the Songs, felt it was fantastic.

"Are you going to release it as a single?" he asked Springsteen with manager Jon Landau standing behind him. "Because it's so topical."

Hiatt writes that Springsteen "winced as if it was a crass suggestion," and Landau replied "No! No! Don't say that."

Perhaps Landau knew the word "topical" doomed the idea of releasing the song in Springsteen's mind.

For the better part of a decade, "Roulette," which Springsteen would remember in his memoir as "a portrait of a family man caught in the shadow of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident," became just another of the prolific songwriter's lost songs. Not even shortlisted for The River, "Roulette" wouldn't officially be released until 1988, as the B-side of "One Step Up" [above]. A fan favorite, the song was a setlist staple on the Tunnel of Love Express Tour before eventually appearing on Tracks another decade later (and The Ties That Bind: The River Collection in 2016).

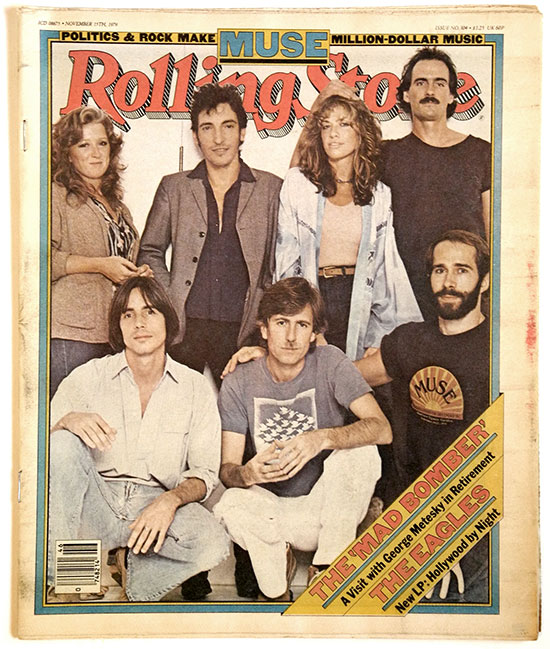

Meanwhile in the spring of 1979, a fledgling coalition of musicians called MUSE (Musicians United For Safe Energy) was in motion following the Three Mile Island incident. The core board included Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, Graham Nash, and John Hall, the former leader of Orleans. Raitt's involvement went back to the time she was approached to raise money on behalf of the Silkwood Defense Fund, which charged that Karen Silkwood, a one-time employee of the Kerr McGee nuclear power plant in Oklahoma, was poisoned by plutonium (Meryl Streep later played her role in the 1983 film Silkwood.) The case was eventually settled, and the Silkwood Estate was awarded $10 million.

In May, Raitt played a concert at New York's Palladium with James Taylor and Carly Simon and announced at a press conference that a petition protesting the continued use of nuclear power, sent to federal and state legislators, had been signed by some 1,000 musicians including Stevie Wonder and several members of the Eagles. The benefit only raised a small amount; Raitt and her compatriots, who had been playing isolated benefits to that point, decided it was time to go big — to plan a world event with an album for the cause. The idea of creating a film as an educational tool was also broached.

Springsteen in NYC, September 1979 - photograph by Joel Bernstein

Springsteen was approached by activist and organizer Tom Campbell about joining the MUSE concerts being planned for the fall. Despite Bruce and the E Street Band's year-long focus on recording in 1979, current events, his experience of writing "Roulette," and perhaps his friendship with Jackson Browne all encouraged him to say yes. It didn't hurt that Bruce and the band were recording in New York City, just 20 blocks uptown. And as he would later reflect in his memoir Born to Run, the MUSE concerts at Madison Square Garden, in late September of 1979, would be his and the E Street Band's entrance into "the public political arena."

Onstage at No Nukes - photograph by Peter Simon

Stepping onstage on the rising-sun MUSE logo, Hall had anti-nuclear songs in his hip pocket called "Power" and "Plutonium Forever," the result of his own self-education after realizing a nuclear power plant was going to be built six miles from his home in Woodstock, New York. Gil-Scott Heron — who, six years later, would join Steve Van Zandt's anti-apartheid project "Sun City" along with Springsteen — had written the song "We Almost Lost Detroit" about the partial meltdown of the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station off of Lake Erie and the subsequent attempts to cover it up.

"And what would Karen Silkwood say to you," Scott-Heron laments in the song, "If she was still alive? That when it comes to people's safety, money wins out every time."

But we wouldn't hear the anguished cries of Springsteen's fictional character in "Roulette" (who doesn't know "who to trust and who to believe") on the two nights that Springsteen performed, documented in The Legendary 1979 No Nukes Concerts by director Thom Zimny.

Springsteen's presence at No Nukes was louder than anything his fellow performers had experienced. Who could forget the cries of "Broooce" dominating the Garden, and singer Chaka Khan leaving the stage thinking she was being booed? As Bonnie Raitt quipped backstage, "It's lucky his name wasn't Melvin." When Tom Petty was told by Jackson Browne they're not booing, they're saying "Broooce," he famously replied, "What's the difference?"

Springsteen's connection to the efforts of MUSE was less conspicuous. While he committed to the concerts, virtually ensuring they would be financially successful, Rolling Stone reported that one of the conditions was that politicians would not receive any speaking time or receive any of the concert proceeds.

MUSE had a manifesto outlining its principles and aspirations for a future "built on the natural power of the sun and for an end to the threat of atomic power plants and nuclear weapons." Springsteen had yet to develop his own platform. He didn't write about the cause, as other performers did, or address the matter at all on stage. But in an interview the following year (later printed in Talk About a Dream: The Essential Interviews of Bruce Springsteen), he revealed a bit of his thinking, suggesting that the E Street Band's very presence and performance made its own statement.

"I don't offer the power of my band casually," he emphasized, regarding their participation in the benefit concerts. "That was something I believed in and was very serious about."

Given that, and the course of his career that followed, there's a sense in which while watching Zimny's film, you're watching the metamorphosis of Springsteen's ascent toward, and perhaps even self-realization about, his coming activism. You can feel it when he dedicates "The Promised Land" to Jackson Browne for "his sense of purpose and conviction." You can hear it in his new material, even without "Roulette." When Springsteen performed his new song "The River," he was singing about more than just the lives of his sister and brother-in-law in the audience. Of course it was personal — as Springsteen recalls in Born to Run, "When my sister first heard it, she came backstage, gave me a hug, and said 'That's my life.' That's still the best review I ever got." But the song's characters were experiencing more universal and unsettling circumstances as America approached the dawn of the '80s.

Onstage at No Nukes - photograph by David Gahr

Onstage, Springsteen kept it light. An overall party fervor dominated the performance, even as he comically ranted about being driving to the unemployment agency in "Sherry Darling" — stuck in traffic on the same 53rd Street where he was recording The River at the Power Station. But "The River" addressed the economic uncertainty that hovered over the country. In 1979 the unemployment rate was over 11 percent. Inflation was rampant, and we lined up in gas lines on even and odd rationing days as a result of Middle East tensions. The loss of manufacturing jobs would persist into the next decade. Outside the shaking rafters of Madison Square Garden, there was a general malaise in the country that would soon play into the coming presidential election.

If Springsteen was putting his toes in the water for a cause, he was equally cautious about his inclusion in the No Nukes feature film and his presence on the big screen in 1980. In his memoir Bumping Into Geniuses, music executive and No Nukes film producer Danny Goldberg remembers how Springsteen was fine including his own songs like "The River" and "Thunder Road" but felt that the inclusion of oldies like "Quarter to Three" and "Stay," "out of the context of a full set, trivialized both his own artistry and the theme of the concerts." Springsteen was eventually assuaged when the directors showed him the cut of the film that included "Quarter to Three," which they felt was so critical to the climax of the original No Nukes film.

Shortly after the Garden concerts, MUSE held a rally at Battery Park in front of more than 200,000 people. Springsteen did not take part, but world events were continuing to shape his views. As the Vietnam films The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now were running in theaters, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, beginning their own Vietnam and shifting the Cold War into a new power struggle. After 15 years of exile, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini came back to Teheran and seized power, forcing the ruling Shah to leave. Three thousand Iranian radicals, mostly students, broke into the United States embassy in Tehran and took 90 hostages.

The nomination of former film actor Ronald Reagan as the Republican presidential candidate would have profound effects on the country (spawning policies that have led to decades of income inequality) and on Springsteen himself. As the nightly news counted down the number of days and reminded Americans that it was yet another day hostages had not been released, it virtually assured that President Carter didn't stand a chance at a second term. The night after Reagan was elected, with Springsteen now on the road supporting The River, he performed at Arizona State University and told the crowd: "I don't know what you guys think about what happened last night, but I think it's pretty frightening."

Springsteen's bio from the Elektra's press release for the triple album of selection from the concerts, December 1979

A pivotal event to come was Springsteen's benefit for the Vietnam Veterans of America, less than two years after No Nukes. A Night for the Vietnam Veteran, part of his August 1981 River stand in Los Angeles, was crucial to that movement, actually saving the organization from going under. The plight of the Vietnam vet would shape "Born in the U.S.A." and its B-side, "Shut Out the Light" (and "The Wall" much later on.)

Before opening with John Fogerty's "Who'll Stop the Rain," Springsteen framed a country still trying to come to terms with the war almost a decade later. In his introduction he offered this analogy: "It's like when you feel like you're walking down a dark street at night and out of the corner of your eye you see somebody getting hurt, or somebody getting hit in the dark alley, but you keep walking on because you think it don't have nothing to do with you, and you just want to get home…. Well, Vietnam turned this whole country into that dark street. And unless we're able to walk down those dark alleys and look into the eyes of the men and the women that are down there and the things that happened, we're never gonna be able to get home."

In Born to Run, Springsteen would recall Vietnam Veterans of America founder Bob Muller giving a short speech on ending the silence surrounding Vietnam before introducing the band. For Springsteen, it was the beginning of lifelong friendships with Muller and Ron Kovic, author of Born on the Fourth of July, and "the start of putting some piece of what I did to pragmatic political use. I was never going to be Woody Guthrie — I liked the pink Cadillac too much — but there was work to be done."

Reflecting in the memoir on what shaped The River tour, Springsteen pointed directly to both the No Nukes and Vietnam Veterans of America concerts, which to him "proved a practical social use for our talents was waiting."

In the years that were to come, he would realize that "practical social use" in a plethora of ways. Over time he would lend his voice and his talents to countless causes, from numerous local New Jersey non-profits to Presidential campaigns; from Freehold's 3M Plant to a world tour for Amnesty International; Artists United Against Apartheid; schools including Neil and Pegi Young's Bridge School; benefits for homeless children, pandemic relief, wounded veterans and their families via the Bob Woodruff Foundation, 9/11 families and first responders, fellow musicians' families, flood victims, victims of the 2010 Haiti earthquake and Hurricane Sandy; the Come Together benefit for Sgt. Patrick King, the American Red Cross, the Robin Hood Relief Fund, USA for Africa, the Christic Institute, the Kristen Ann Carr Fund, the Rainforest Foundation, the John Steinbeck Research Center, the Count Basie Theatre, Doubletake Magazine, MusiCares, TeachRock; benefits to fight AIDS, Parkinson's Disease, ALS, and more. In the years that were to come, he would realize that "practical social use" in a plethora of ways. Over time he would lend his voice and his talents to countless causes, from numerous local New Jersey non-profits to Presidential campaigns; from Freehold's 3M Plant to a world tour for Amnesty International; Artists United Against Apartheid; schools including Neil and Pegi Young's Bridge School; benefits for homeless children, pandemic relief, wounded veterans and their families via the Bob Woodruff Foundation, 9/11 families and first responders, fellow musicians' families, flood victims, victims of the 2010 Haiti earthquake and Hurricane Sandy; the Come Together benefit for Sgt. Patrick King, the American Red Cross, the Robin Hood Relief Fund, USA for Africa, the Christic Institute, the Kristen Ann Carr Fund, the Rainforest Foundation, the John Steinbeck Research Center, the Count Basie Theatre, Doubletake Magazine, MusiCares, TeachRock; benefits to fight AIDS, Parkinson's Disease, ALS, and more.

Flashing back to 1984: Stevie Van Zandt is with Bruce Springsteen, each playing their own records to each other following Van Zandt's departure for a solo career. As he recounts in his autobiography Unrequited Infatuations, Van Zandt tries to dissuade Springsteen from releasing "Dancing in the Dark" but posits a big idea.

"You know how people do big events…. what if you made every single show in every single city a fundraiser? Donate… I don't know… some percentage, something. Not once in a while. Every single show.

"Just like you used to sign every autograph while we waited for hours on the fucking bus," Van Zandt went on, "this would connect you to every town."

This could be the start of something big: Springsteen takes in the No Nukes crowd from higher ground - photograph by Bill Webber

Harry Chapin had planted a similar seed with Springsteen the year before No Nukes, as Springsteen recalled at a 1987 tribute to the late singer/songwriter/activist: Chapin "said one thing that I'll always remember. He said, 'I play one night for me, one night for the other guy.' And later on, I was trying to put my music to some pragmatic use, I remembered what he said. Not being bent to extremism, I wasn't as generous as he was… but he's probably laughing right now."

Bill Ayres, the co-founder of World Hunger Year (now Why Hunger) with Chapin, first interviewed Springsteen back in 1974 on the ABC radio network. As Ayres told Backstreets, a seminal moment came when Chapin leaned out of a Los Angeles hotel room, seeing Springsteen walking in a courtyard below, and shouted, "What are you going to do about hunger, Bruce?" That direct appeal to Springsteen, along with follow-ups from Ayres and the prompting from Van Zandt, led to the singer hosting local community food banks at his shows and exposing millions to the widespread problem in their own communities. Springsteen's anti-hunger work has continued for four decades.

That weekend in September 1979, as he turned 30 in the Garden, Springsteen was stepping out of his own skin, circling around seasoned activists and daring to let himself be filmed for the big screen. Time might have made the performances themselves legendary, but they're even more significant in the context of his own journey that followed.

Steve Wosahla attended the September 22, 1979 concert; more recently, he writes the column "My Back Pages" for Americana Highways

|