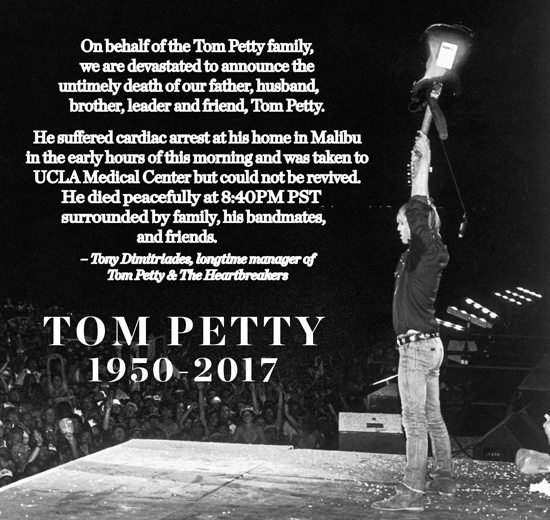

Tom Petty's untimely death at age 66 leaves a great space open, one he filled in a way few musicians, whatever their level of popularity or record sales, can imagine or occupy. Petty aged, but he didn't change much: his showmanship, his setlist, and his band all remained in place. Even when he'd make a record without the Heartbreakers, they'd dutifully assemble to hit the road with him. And when he didn't make a record, they'd play for the hell of it. That was the case with their 40th anniversary tour, which ended a week ago.

Coming from Gainesville, Florida, Petty shared much in common with Bruce Springsteen, his New Jersey kindred spirit. After kicking around and honing their crafts, they both broke out with their third record (Jimmy Iovine had a hand in both, coincidentally). They overcame legal problems that threatened to keep them from moving forward. And of course, they both had father trouble. Still, when they finally met, probably sometime in the mid-'70s, they did the rocker thing, loading up on eight-track tapes and driving through Los Angeles to the water's edge.

Coming from Gainesville, Florida, Petty shared much in common with Bruce Springsteen, his New Jersey kindred spirit. After kicking around and honing their crafts, they both broke out with their third record (Jimmy Iovine had a hand in both, coincidentally). They overcame legal problems that threatened to keep them from moving forward. And of course, they both had father trouble. Still, when they finally met, probably sometime in the mid-'70s, they did the rocker thing, loading up on eight-track tapes and driving through Los Angeles to the water's edge.

They worked together in a loose sense: the No Nukes shows in 1979, and the first Bridge School benefit concert in 1986 (okay, they were both there). But they never really collaborated, and maybe it would have felt gimmicky anyway. Petty was always unguarded: anyone who remembers "Don't Come Around Here No More" will tell you that. And anyone who read Warren Zanes' excellent biography will, too. (To really experience Tom Petty, go to YouTube and watch him with Garry Shandling, probably the most fascinating 20 minutes you'll spend today.)

Their careers took different paths. As a child, Tom Petty met Elvis Presley. As a working musician, he and his band backed Bob Dylan. Petty battled his record company over how much his records would cost; Springsteen built enough credibility with Columbia that putting out Nebraska merely took Walter Yetnikoff one listen. Springsteen and Petty made summational records in 1987, after which Petty made Full Moon Fever without telling all the Heartbreakers. Springsteen dismissed the E Street Band and made Human Touch and Lucky Town.

Another difference was MTV. At the dawn of the '80s, Springsteen spent years making records in New York recording studios. Tom Petty made videos that fed the earliest demands for the new format. That's how most Gen X fans caught on to him, whether it was the stark, black-and-white reading of "A Woman in Love (It's Not Me)" or the post-apocalyptic road trip that played out in "You Got Lucky." Tom Petty reached people with images, and in a big way: he was a quick study with videos, and he rode cable to greater success. (Springsteen did alright himself, just don't you worry about that.)

Another difference was MTV. At the dawn of the '80s, Springsteen spent years making records in New York recording studios. Tom Petty made videos that fed the earliest demands for the new format. That's how most Gen X fans caught on to him, whether it was the stark, black-and-white reading of "A Woman in Love (It's Not Me)" or the post-apocalyptic road trip that played out in "You Got Lucky." Tom Petty reached people with images, and in a big way: he was a quick study with videos, and he rode cable to greater success. (Springsteen did alright himself, just don't you worry about that.)

And Heavens to Murgatroyd, did Tom Petty ever have the songs to back him up: "Louisiana Rain," "Nightwatchman," "Runaway Trains," "The Last DJ," "I Should Have Known It" — and these are just the back-benchers, but great ones nonetheless. Their sole misfortune was coming from the same imaginative soul that produced a 20th-century American songbook that carried over into the next, codified by jukeboxes from Gainesville to Malibu, and a Greatest Hits collection that's sold 12 million copies in the U.S. He made great records, too, long-players in the true sense, none more splendid than Wildflowers, none more passed over than the underrated Let Me Up (I've Had Enough), none more celebrated than Full Moon Fever. Or Damn the Torpedoes. Good work if you can get it, I say.

No, great work.

Godspeed, Tom Petty.

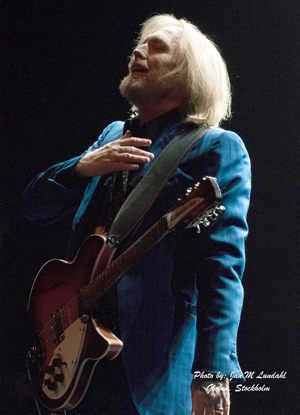

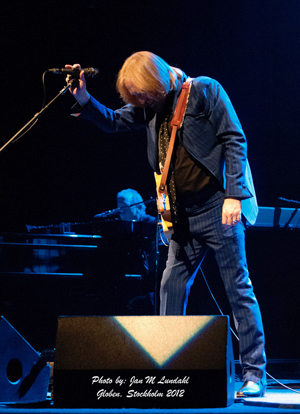

- Jonathan Pont reporting - Stockholm 2012 photographs by Jan Lundahl