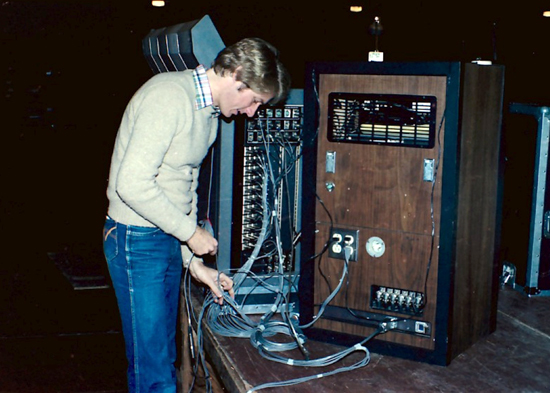

Bruce Jackson on the River tour at Red Rocks, August 17, 1981. Photograph by Watt Casey, Jr.

In Thom Zimny's documentary The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town, Bruce Springsteen noted that more than anything else, he wanted to be great. Of course, Springsteen set that high standard for himself not just in the studio, but on the concert stage as well. The 1978 Darkness tour would pose new and especially difficult challenges for him and his organization. For the first time ever, the majority of his shows would have to be performed in the larger arenas he once swore off (after a brief experience as opening act for the band Chicago in 1973). Clearly, some help was going to be needed in an adventure that must have been more than a bit intimidating.

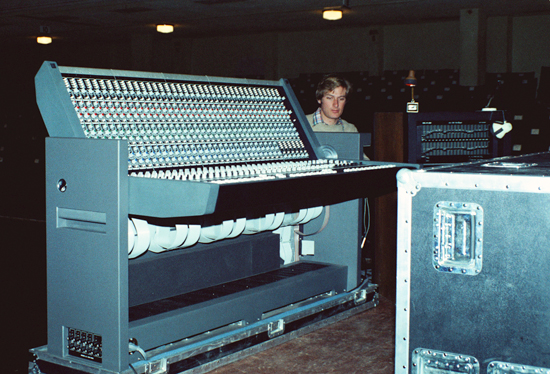

Luckily, Bruce Jackson was available. Jackson entered Springsteen's circle as an already-established "superstar" himself, in terms of his reputation and experience in the world of professional concert audio. On more than one occasion, Jackson was at the center of historic breakthroughs in the industry. For example, he co-invented the foldout mixing console, which became standard sound equipment for many years at virtually every live entertainment event, until its replacement by yet another Jackson innovation. He was so down-to-earth, however, that it was surprising to learn that Jackson was born into a very wealthy family in his native Australia; in fact, the house he grew up in later set an Australian record for the most expensive home ever sold.

Like Phil Spector, one of Springsteen's main musical inspirations, Bruce Jackson began to forge his reputation as a sonic genius while still a teenager. In 1967, he and one of his school chums, a fellow "eager electronics enthusiast" named Phil Storey, founded Jands, the premier Australian concert-audio, lighting and staging company. ("Jands" was an abbreviation of "Jackson and Storey.") Three years later, Jackson sold his interest in Jands to work in the U.S. with Pennsylvania-based Clair Brothers Audio, which quickly was developing its own reputation for excellence and innovation in the rapidly evolving concert-sound industry. When Elvis Presley began supplementing his Las Vegas shows with concert tours of the U.S., Clair Brothers Audio was contracted to do the sound, and Bruce Jackson quickly became Presley's personal concert sound designer, monitor engineer, and occasional house engineer on the road from 1971 until Elvis's death in 1977. Jackson was setting up the sound for Presley's next concert when he got the news.

Just months after Elvis died, Jackson was approached by the Springsteen organization. In short order, he became Bruce Springsteen's concert sound engineer and remained so for the next decade, from the Darkness on the Edge of Town tour through the end of the Tunnel of Love Express Tour. After their professional association ended, Jackson remained a famous and respected innovator in the field of electronic audio and continued to work with many other big names in entertainment, but he always held the time he spent working with "the other Bruce" in very high regard. Jackson's and Springsteen's efforts raised the bar immensely, truly revolutionizing the level of sound quality that audiences could expect to hear at large-scale concerts.

Backstreets contributor Shawn Poole tracked down Bruce Jackson in late 2010 at the Australian offices of Dolby Laboratories, where he served as Dolby's Vice President of Professional Live Sound Products. Shortly thereafter, while on vacation in the U.S. at his California home, Bruce granted his first-ever interview with Backstreets. The interview is extensive and constitutes Jackson's first published interview to cover his work with Bruce Springsteen in such detail. Tragically, just a day after this interview was concluded, Bruce Jackson was killed when the single-engine plane that he loved to pilot crashed during a solo evening flight near Death Valley National Park. Backstreets is honored to publish this interview as a lasting tribute to a man whose amazing life story became a very important part of the history of Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band.

Let's start with how and when you began working with Bruce Springsteen.

I had been working with Elvis Presley, and he had died. Bruce had plans to come out on tour [in 1978]; he was getting going again. They were having some problems [with sound] out on the road… and so I was asked if I would go out there and basically just lend a hand, just to kind of get things sorted out. There was no intention to stay on, but just to go and help.

How much did you know about Springsteen's music at that point?

Very little. In fact, I was pretty much a neophyte. I'd heard a little bit about Time and Newsweek and the "new Dylan" kind of stuff, but I wasn't really that familiar at all, so it was fun to go out there and discover him. And so I went out there, and it turns out I was able to offer a lot of help in a lot of different areas. Bruce and I got along really well, because we're just about the same age. So it extended: I ended up staying, and that became my career, as his concert engineer, for the next ten years. And then later I came and gave some advice when he was touring Europe. I took my daughter Alex along; we went to Switzerland and some other places, just to add some help.

This was after you had finished your official stint?

Yeah, with the new band [on the 1992-93 Human Touch/Lucky Town Tour.] It was just like, "Hey, would you mind coming out and just helping us sort some things out?" But I wasn't mixing then. I was purely out there to say, "Hey, you know, you can do a bit of this" and "How about that?" and that sort of thing.

Did you stay on through the six-week Amnesty International Human Rights Now! Tour, which directly followed the Tunnel Tour in '88?

No, actually, I didn't do that. My son was born when we were in Germany [shortly before the end of the Tunnel tour], so I said to Bruce, "I'm going to go home and be with my newborn." He was very generous — gave me a jeep for Christmas one year.

Bruce Jackson on the Darkness tour: December 15, 1978, at the Winterland Ballroom, San Francisco, CA. Photograph by Michael Murashko

Jumping back to your first full tour with Springsteen, the Darkness tour, are there any particular shows, venues, or behind-the-scenes anecdotes that stand out for you personally?

The Capital Centre [August 15, 1978]. That was an amazing show. I liked the Darkness album, but I really preferred the way things came across live. I think the studio stuff was a little bit stiff and structured at times, whereas the live show was thick with atmosphere and energy. I think those shows like the Capital were all very memorable because it was all very free-form. Later, once we started playing stadiums and stuff, it became much more structured, and the setlists were much more predictable. Back then, however, you may as well have just torn up the setlist and thrown it away. It would just go to all these different, cool places.

What I found particularly interesting were the dynamics: he would bring it up, and then he'd bring it down. Later on, it seemed at times that it'd stay down too long, but back then it would just ride wild. He played with those sequences a lot, like he'd follow this song with that one and that would work, and sometimes he'd try turning it around the other way, and it might not work. The songs, too, were highly variable as far as how they'd sound each night... really great textures.

And Bruce was playing more with the guitar. He was doing sustains and playing solos, whereas I think he kind of backed off on that later on — his guitar became more of a texture, and he relied more on Nils to play those lead parts. But back in '78 there was heavy sustain going on. We would go through sustain pedals — the same brand, the same manufacturer of the distortion box that you'd play through — and they'd each sound a little different. So we'd go through and select the best-sounding ones. That was typical of almost anything we did: we did our best to get the best.

I also think it was the energy and the way the audiences would respond. The emotion of those shows was just fantastic.

How about what was happening behind the scenes?

Well, I had always been spoiled on the road. I hadn't done a tour on a bus before, which was pretty wild after having toured for so long. That was good — there was camaraderie amongst all of the different band members and crew that was different. I think that usually doesn't exist today; everyone's very separate, and they travel differently.

During that tour, Bruce came over to my house in Santa Monica with Jimmy Iovine. Bruce and Jimmy came out in... I think it was a Corvette or something, only two seats. So Jimmy stayed at my house while Bruce and I drove off. We left Jimmy for the day. He was just lost — didn't know what to do.

Was the house still standing when you got back?

It was, but I was a bachelor at the time, so it was pretty much a "bachelor house," if you can imagine that. I took Bruce down to Coast Music [in Costa Mesa, CA], who at the time were the Takamine distributors in the U.S. The Takamine guitars don't necessarily sound that great acoustically, but they actually did an amazing job on the pick-ups they put inside. And so to improve his sound, Bruce then bought about fifteen of these Takamine guitars, and that's when he started playing them. The rest of the band was mad at me, because I was not being very "American," and I should be getting Martin guitars, that sort of stuff. And here we were getting Japanese guitars that were kinda like mid-level. But they were great from a pick-up point of view.

And at least some of those Takamine guitars have since been displayed in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's Springsteen exhibit.

Oh, I didn't know that. So that's fun, after I was considered a traitor [laughs]! There also was this guy from back then, his name is Watt Casey. He was basically a fan who came up to me from the audience one night, and he had taken these great black-and-white pictures. I showed them to Bruce and next thing I know, they start using his pictures over the years. I kinda gave this unknown guy his start as a professional photographer.

Yeah, he has some beautiful photos featured in The Promise [The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story] box set, as well as the Backstreets book and Dave Marsh's book Bruce Springsteen On Tour [1968-2005], too.

He's contacted me a few times over the years just to thank me... a nice guy from Texas; he's a rancher, I think. Dave Marsh, by the way, used to talk to me a lot about Elvis, and he credits me in his coffee-table book [Elvis] for the conversations we had.

Winterland, December 15, 1978. Photograph by Michael Murashko

Back in '76, Bruce began playing his first arena shows as a headliner, and the Darkness tour that followed consisted mostly of dates at larger arenas. The move to larger arenas was one that Springsteen was very reluctant to make at first. What was done in your area of work to help in alleviating Bruce's concerns?

At the time, Bruce had a 100-foot guitar cord, because he'd get passed 'round the audience, run around the stage, and all that. Back in those days, the wireless stuff was really pretty crappy. I'd still choose a cord today if people wouldn't mind being tethered close enough; obviously with Bruce, that's pretty difficult.

Basically, you can't have what's called a high-impedance pick-up running along a long cord, so I built this little circuit that sat inside his guitar — you know, his famous guitar on the Born to Run cover. I was digging into that and burying electronics in there that boosted the signal so that when it went along the long cord, the high frequencies wouldn't get absorbed and basically rolled off.

He also used to have a lot of problems because he'd sweat like crazy, and all that sweat would go inside the guitar. Salt and electronic switches don't go together well, so the connector for his guitar used to give us all sorts of problems. So I made a special switch that used what's called reed relays. You can switch them with a magnet so they make the connection. We were able to bury all of this inside a block of rubber in the guitar. That also made a big difference.

From an audio point of view, what you need to do is isolate things and get the cleanest sound that you can possibly get out of each of them. At the time, that wasn't the situation up on stage; everything was bleeding into everything else: bass guitars and lead guitars would bleed into the drum mics, and all of that sort of stuff. So I set about working on each individual member's instruments to get the very best sound out of it.

For instance, Danny Federici played the B3 organ and had a Leslie. The Leslie is that rotating speaker that you hear, and it was picking up all sorts of noise. So we built this great big box that the Leslie went inside, along with the microphones, so we'd get a very isolated, clean sound.

Bruce used to have his [onstage monitor] so loud, and the stage used to pick up lots of noise — footsteps and everything else, up through the stage. So I instigated where we'd actually run Bruce's microphone stand all the way down [through the stage floor] to the ground, resting on real solid ground, even though the stage floor might be twelve feet up. Then all that stage noise doesn't come up through the mic.

There were lots of different things to improve the sound quality, that extended from choice of microphones, choice of monitors, the actual people doing those jobs... changing everything, basically. We made big strides and went from kind of a really pretty ratty sound, I think, to winning all sorts of awards for the sound quality.

EARLY AUDIO ADVENTURES OF B.J., BIG MAN, FUNKY, AND G-O-D

An addendum in Dave Marsh's February 1981 Musician magazine cover story on Bruce Springsteen ran down the technical details of Bruce and the E Street Band's musical equipment at the time. Among other things, it revealed that Clarence "Big Man" Clemons' horns were each "miked with a device invented by Clemons and Bruce Jackson." Garry Tallent ("Funky" to his friends, of course) also related all of the specs of "my own personal Funky setup, which I've thought about long and hard... The rest is up to God and Bruce Jackson."

|

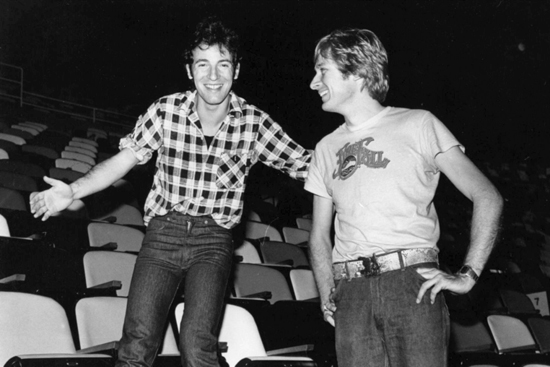

How about those legendary soundchecks?

Yeah, that was with me... wandering with Bruce around the arena. It was interesting, because he would come out with me every day, and we would go through all of the different instruments and we would work on the sound to where he was comfortable. But I think it also was just getting comfortable with the arena, and just getting comfortable with the whole concept, more than the very specifics.

We would walk around while the band played whatever the appropriate song was. Either Bruce or I would be tapping the top of our head — meaning "from the top" — and they'd start again. He'd say something like, "I'm kinda hearing this back here; why is that?" For example, when you'd get a long way away from the sound system, the high frequencies roll off — because the sound is absorbed in the air, and it absorbs the higher frequencies before it absorbs the lower frequencies. So Bruce would say, "Well, look, these people in the back, they haven't paid as much as the people in the front, but I want them to get an equal show." And I'd say, "Well, we can certainly do stuff about that."

One way was to add what we called the "afterburners." We could add these delayed super-high [-frequency speaker] cabinets [towards the back of the arena], kick back up the high frequencies that are lost in distance, and give the people in the back an experience very similar to the people in the front. I'd say, "It's gonna cost money," and he'd say, "Fine. Just do it."

We'd run into places that were acoustically "less-than-perfect" — just horrible-sounding. He'd say, "Hey, B.J., what can we do about this?" And I'd say, "Well, we can hang curtains, do this, do that." There was a whole bunch of little bits and pieces we could change. We could change the way the P.A. was set up and actually get around a lot of issues that way. We did that in quite a few different venues, back when people really weren't conscious of that sort of stuff at all.

It was all because of our success in the arenas. For example, we played The Forum in Los Angeles [on the Darkness tour], and they were not very nice to us. They turned the lights on during the last songs, etc. So come the next tour, Bruce said he's never gonna play The Forum again. [NOTE: Springsteen didn't return to The Forum as a headliner until 2002, for one show on The Rising tour, and he has yet to play there again.] So he asked what other options were available. The only one was the L.A. Sports Arena, which had a horrible reputation for sound. So he met [Tour Director] George Travis and me there and said to me, "Well, this is where we're gonna play. What can we do?" So I ordered up all of these custom-made drapes and we put them all over the room. It was a major, major change in this venue, and the differences were night and day. People were just astounded. In fact, they kept using it. The Sports Arena became a popular venue, after not having done many shows at all, because of our success, and they actually kept a lot of that acoustic treatment.

I think that's what distinguished what we were doing. Bruce would go around [the arenas] and ask questions. Being a very smart guy with a great memory, when we'd run into a situation he'd start saying, "Well, you said we could do this, right?" and I'd say, "Yep, we can do that, and that'll do that, etc." So he actually became quite attuned to acoustics, the stuff that you can do and the stuff that you can't do.

That whole process, however, was very much about his "getting in the comfort zone," so we'd circle the entire arena, and it could take a long time. The band had to just get up there and almost play like a jukebox while we walked around.

The legend is that some of the soundchecks lasted longer than the shows themselves. Is that so?

You know what, I probably don't want to remember those days in that much detail [laughs]. The shows were pretty long, so I doubt it. On the other hand... the part where he'd be out with me listening to instruments, then walking around the arena, and then I'd be calling in adjustments to whoever my assistant was in the mix position that day... that was just a part of the soundcheck. Then he'd go up on stage and they'd play with different songs; he'd test the band and see if they could remember all of these old rock 'n' roll songs that he'd drag up. Amazingly, the band would generally know them pretty well. So that was all part of the process. And probably, if you add all that together, it did go on for hours.

The Two Bruces — "B.J." and "The Boss" — sharing a laugh and a quick break from one of their legendary soundcheck walks at Madison Square Garden in August 1978. Photograph courtesy of Bruce Jackson

Do you have any specific memories about the European leg of The River Tour in 1981? The band played with incredible urgency on that leg, but Bruce also started experimenting with cover songs that had a different sonic palette than the work that preceded it: songs like "Trapped," "Run Through the Jungle" and "Follow That Dream." Do you believe that the sound of the band evolved significantly in Europe?

Yeah. I think it was an emotional time, and I think Bruce must have been going through something, because it did get very experimental — you know, playing with different bits and pieces of the show. That [European leg] also was great because he hadn't really hit the big, big time at that point, and so people were discovering him, and the whole energy was just getting bigger and bigger and bigger.

Generally, the band had kept on getting very, very tight. There had been issues with tempo. You never really would know where a song would end sometimes; you know, you'd start at one tempo and be ending at some other tempo. And a lot of those things got better and better as time went by. The band just tightened up and tightened up. I remember the band just evolving generally over time, and I don't think I was all that conscious of the "big spurts."

One of the innovations you first developed during your tenure with Elvis Presley, and that continued with Springsteen in the arenas, is the elevation of speaker cabinets and other sound equipment at live concerts. Audiences benefit from this in two ways: it helps to improve the projection of the sound throughout the venue and it creates better sight lines towards the stage. Can you tell us how this innovation came about?

Elvis was selling out large sports arenas, and the way things worked back then was that the speakers were all stacked on each side of the stage. This was a horrible thing from a sound-coverage point of view. When everything's down on the ground, you kill the people in the front rows and the people in the back can't hear, whereas if you hang it up high, you get much more even coverage between the front and the back. Today, it's become super-sophisticated, with these new line-array systems that let you very carefully control the sound much better.

But the biggest issue then, from "Colonel" Tom Parker's point of view, was that it blocked lots and lots of seats that he couldn't sell. So he told us we needed to get the sound up, which the ice shows [Ice Capades, Ice Follies, etc.] were doing already with a very basic rig, much smaller than ours.

At the time, generally things weren't done on a national or international basis. One sound company didn't usually set up sound equipment for the same band all around the world. Acts usually had their own mixer, and they'd come into a region and use whatever sound company was available in that region. Showco did the Texas-area shows, McCune did Northern California, etc. And so all of these companies were being forced to try and hang the sound, and there were all of these very questionable, dangerous kinds of rigs that they had.

For example, at Madison Square Garden, they had a block-and-fall [hand-held pulley system] where the crew was pulling up these platforms with the sound on it, and they were tilting and going up and down; the whole thing was very, very scary.

So I led the innovation of using a chain motor to hang this stuff. At the time, we had just one chain motor for hanging our custom sound rig from the center above the stage; that was the first use of a chain motor in rock 'n' roll. Now, a typical show will have 150 or so chain motors, all rigged for usage on a daily basis. So we pioneered that hanging, but it wasn't for sound quality, originally. It was to sell more seats and make more money.

I also understand that because of your connections to Elvis Presley, you once were able to take Bruce Springsteen on his first official visit to Graceland, shortly after Elvis's death.

Yeah. It was on the Darkness tour; I don't recall the exact date. [NOTE: The Darkness tour had a stop in Memphis, Tennessee on July 19, 1978, followed by a show in Nashville on July 21, so the visit most likely occurred on July 20.] I took him there, and he was shown all around the place. We spent some time with Vernon [Presley, Elvis's father, who still was living at Graceland at the time], chatting. I did the introductions. I think Bruce got a real big kick out of, you know, going around, seeing the Jungle Room and all of the stuff you'd hear about. Here he was, after jumping the wall and all of that previously, finally having an official visit, with the help of Elvis's sound guy.

And this actually was before Graceland was turned into a museum.

Oh, yeah — it was nothing like what it is now. And now the Lisa Marie plane, complete with my [sound system] installation, is right across the street from Graceland.

What happened was, I got a call at, like, two o'clock in the morning. "The boss wants to see you." So I put my jeans and T-shirt on, go up to Graceland, and there's Elvis sitting in bed with his karate jacket on and his gold-plated gun beside him. He said, "Bruce, the goddamned sound system on the goddamned plane is all fucked up! I don't care what it costs — fix it, or I'm gonna shoot the goddamned thing out!"

Everyone was nervous, because they knew that if he didn't like anyone on TV, he'd actually shoot the TV. The consequences of shooting in a plane, obviously, can be more dire than shooting at a TV set.

It's funny, because Elvis was kind of threatened, I think, by a lot of the more recent artists at the time. People think he'd be listening to other people's music, but he'd often be watching Monty Python or stuff that people just wouldn't expect.

When I was working at Clair Brothers Audio, I lived out in Lititz, PA, where I got into flying at Lancaster Airport. So with my girlfriend at the time, I flew the Lisa Marie from Memphis down to Miami and put in ten big JBL speakers, and SA power amplifiers, and put this big sound-system on it. Until I'd done that, everyone stayed a little nervous.

A MAN OF HIS WORD WHO KNEW GOOD WORK WHEN HE SAW IT

"Having eight of my images appear in The River songbook is due to the efforts of the late Bruce Jackson, who at the time was mixing sound for Springsteen's tours… I'll never forget walking up to him, standing near the semis that would soon take the tour's sound equipment to the next show, once they had finished their [November 8, 1980] date at Reunion Arena in Dallas. Carrying my Ilford box of 11 X 14 black-and-white prints I had made in my tiny bathroom darkroom in Austin, I handed it to him and asked if he would show the photos to Springsteen. He glanced through them and said, 'These are good. I'll make sure Bruce sees them.' The next day I got a phone call from Jimmy Wachtel, who was designing The River songbook, telling me they wanted to use eight of my photographs!"

— music photographer Watt Casey, Jr. in his newly published book My Guitar is a Camera

|

Was it a challenge to find the "new" sound of the E Street Band back in 1984, with Nils Lofgren's tone in the place of Steve Van Zandt's and a female voice, that of Patti Scialfa, added to the mix?

I think Nils played a much more complementary guitar, whereas Steve played against the music at times, if that makes sense.

I've heard others make that observation, too.

Yeah... Nils made a much better guitar bed. Bruce's guitar-playing kind of creates a texture that doesn't really belong way up front unless he's playing a solo, which he wound up doing less as time went by and relied more on Nils for a lot of those parts.

Bruce actually has gone on record as saying that he thinks that Nils is the best guitarist in the band.

I definitely agree. Patti's voice also made mixing a bit more challenging. She was up in the same register as a lot of the other stuff that was kind of competing. It's usually nice when you're mixing to have space and put things in certain registers, and the better you can maintain the area in that register, the more room you've got for mixing in, say, the vocals. It depended on what the song was or what the style of singing was, but sometimes it was kind of pushed, and there was a lot of energy, and sometimes I had to really concentrate on settling back and getting the fullness of the vocal. Choice of microphones and all of those things can make a big difference, however.

Speaking of the Born in the U.S.A. period, your former wife Ruth [Jackson, now Ruth Davis] sang beautifully on the studio version of "My Hometown." Prior to the addition of Patti Scialfa to the E Street Band, this was one of the few officially released recordings to feature female background vocals. Can you tell us how that came about?

We visited Bruce in the studio when he was working on that record. The guys in the E Street Band were trying to sing these parts, and they were having problems getting what they were looking for. I knew that Ruth could sing; she wasn't a professional singer, but she could sing. So I said to her, "You could sing that." Bruce overheard me and said, "Oh, can you?"

So he took her out into the studio and coached her. She came back the next day and maybe a couple of more times, and he continued coaching her, and she sang on "My Hometown" and, I think, a few more songs that didn't make it to the album. [NOTE: Though she has yet to be credited officially, it is believed that Ruth also performed the beautiful closing vocals on Springsteen's 1983 recording of "County Fair," first released officially in 2003 as a bonus track on The Essential Bruce Springsteen.]

Normally, you'd just call up a professional singer and they'd sing the parts, but it was interesting that we just happened to be there, I noted that she could probably do a better job than what they were doing, and they ended up using it. I also remember when we were getting ready for the Born in the U.S.A. Tour, I went down and stayed at [Springsteen's] house, and I remember hearing him dancing upstairs, practicing his dance steps [laughs].

My next question jumps forward again to the period after you officially left the Springsteen organization. In 1992, on his first tour after the Tunnel of Love Express Tour and Human Rights Now!, Bruce Springsteen began his ongoing association with Audio Analysts, co-owned and operated by Albert Leccese, a great innovator in his own right who died of lung cancer this past summer. Did you know Albert at all?

Oh, yeah. I knew Albert for years. What happened was... George [Travis] didn't like Clair Brothers Audio so much. So when I left, that was the end of the relationship with Clair Brothers. It went on for a little bit longer with the Amnesty International tour, and then that was the end of that, because I was the one that was responsible for working with Clair.

George was good friends with Albert, as was I over the years. Audio Analysts actually started off licensing Clair Brothers' technology for the Olympics, and the agreement was they were never supposed to compete with Clair Brothers in the [audio equipment] rental business. But they did. So that became the beginning of a competition between the companies. It was always a friendly competition, though, at least at the lower levels. Albert was a really nice guy. I actually e-mailed him and communicated with him just a day or so before he passed and got to catch up and say goodbye. Albert's brother Mario is a really nice guy, too. I kinda feel sorry for Audio Analysts. We used to get awards for the sound, but I don't think they ever did [for their work with Springsteen]. With all of those guitars up on stage and the whole style of things now, it's pretty tough to get good sound, and they do.

Wembley Stadium, London, England, June 25, 1988. Photograph courtesy of Bruce Jackson

A lot of technological changes in the presentation of live popular music occurred during the ten-year period that you worked with Bruce Springsteen. Bruce also began playing outdoor stadiums in many of his concerts from 1985 onward. How did those changes affect your work on Springsteen's tours?

Well, we led the way in making a lot of those changes. For instance, those "afterburner" delays we used. When we played the stadiums, we actually put these "delay towers" up, which were those [super-high-frequency] speakers on poles. There was one set about 200 feet back and another set about 350 feet back, and they were there to improve that stadium sound quality. The Rolling Stones were touring Europe around the same time as we did, and we went around and made a great big difference with these delays. And the Stones weren't doing it until the promoters all started saying, "Hey, you guys have gotta start thinking about doing the stuff that Springsteen's doing, because his sound is way, way better than yours." So we certainly influenced things and changed things.

We had a lot of trouble getting a consistent drum sound in the stadiums; it would just be highly variable. A combination of the live sound and drum triggers helped to get that powerful sound that we were going for. The P.A. that we were using in some of those stadium shows, where we actually had 360-degree seating, was just massive... a couple hundred of Clair Brothers' signature S4 [speaker] cabinets at the time.

It was good to have the support to do that sort of stuff, too, because Bruce would hear the difference. And, as I mentioned, he got smart from asking questions. "I'm standing here and I'm listening to this; why?" I'd explain it to him, and next thing, that was in his "memory bank." So later he would say, "Well, you did this back there; why don't we do that here?" It was interesting to see. And George Travis... he was full of piss and vinegar and lots of energy, and we took it as a challenge each day: what can we do to really improve the sound quality in this facility? We went the extra mile, and it probably cost extra money and a lot of extra time and energy, but it sure paid off as far as the end results go.

Indeed it did. On behalf of all Springsteen fans who were fortunate enough to experience them, thank you, Bruce Jackson, for all of those great-sounding shows over the years.

- interview by Shawn Poole - special thanks to Terri Jackson and Lawrence Kirsch

Bruce Springsteen's Message to Bruce Jackson's Family from Bruce Jackson Memories on Vimeo. This message was played at the public memorial for Bruce Jackson held in Australia's famous Sydney Opera House Concert Hall on February 25, 2011. Jackson served as a key advisor for the Concert Hall's 21st-century sonic upgrade.