|

There's a game we play, music fans like us. Get a few of us together — in a bar, in a car, standing in one of the many lines we stand in — and this sort of thing is bound to start up: if you could go back in time, and see one show....

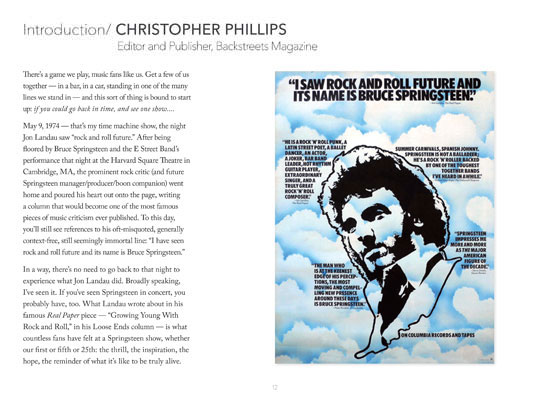

May 9, 1974 — that's my time machine show, the night Jon Landau saw "rock and roll future." After being floored by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band's performance that night at the Harvard Square Theatre in Cambridge, MA, the prominent rock critic (and future Springsteen manager/producer/boon companion) went home and poured his heart out onto the page, writing a column that would become one of the most famous pieces of music criticism ever published. To this day, you'll still see references to his oft-misquoted, generally context-free, still seemingly immortal line: "I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen."

In a way, there's no need to go back to that night to experience what Jon Landau did. Broadly speaking, I've seen it. If you've seen Springsteen in concert, you probably have, too. What Landau wrote about in his famous Real Paper piece — "Growing Young With Rock and Roll," in his Loose Ends column — is what countless fans have felt at a Springsteen show, whether our first or fifth or 25th: the thrill, the inspiration, the hope, the reminder of what it's like to be truly alive.

Still, the power of the May 9, 1974 show in particular has always intrigued me. Not only because of the performance itself — the very thing that gave Landau, as he wrote in his column, "sores on my thighs where I had been pounding my hands in time for the entire concert" — but also because of its towering importance to Springsteen's career. Landau's 2,000-word avowal, written in the wee hours ("as fast as I can for fear I'll chicken out") sparked a true turning point. This night was the proverbial butterfly that flapped its wings and changed everything.

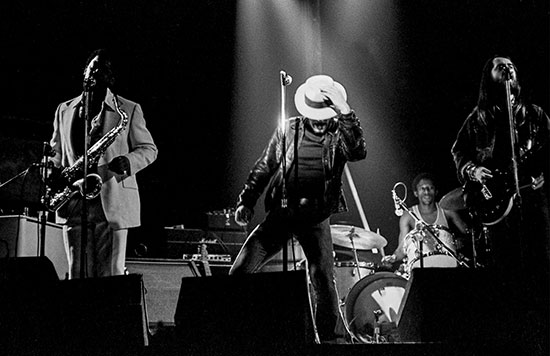

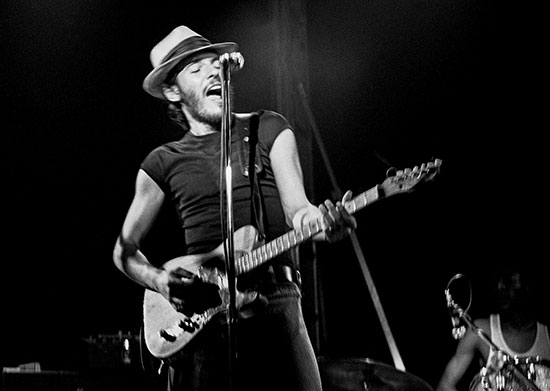

May 9, 1974 - photograph by Barry Schneier, from Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future

Thirty years later in the New York Times, Nick Hornby called "Growing Young With Rock and Roll" a "lovely piece of writing," as well as "influential, exciting, career-changing, and subsequently much derided and parodied." He's right, it's all of these — but let's underline "career-changing."

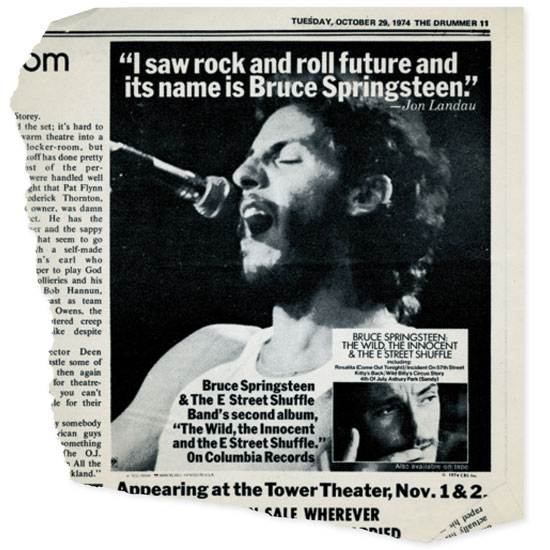

Until this night in Cambridge, by all accounts, Columbia Records was near giving up on Springsteen. In 1973, they had released his debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J., as well as its follow-up, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. By May 1974, after disappointing initial sales, they were letting these albums languish with little promotion, even advising radio stations not to play them.

Springsteen sets the scene well in his memoir, Born to Run: "We had no money and were receiving no record company support…. Our fortunes at the record company had fallen. Our fathers there" — i.e., John Hammond and Clive Davis — "were gone… and if we were a success, we would be a feather in no one's cap. The men who would've taken the credit had vanished. We'd been orphaned." Bruce was "frustrated by our record company's lack of promotion."

As the old saying goes, be careful what you wish for. Because thanks to Landau's column, Bruce's label would have a PR dream for a hook: "rock and roll future"!

Suddenly, a $50,000 publicity campaign (more than a quarter-million, in 2018 dollars) kicked into gear. In Rolling Stone, in local papers advertising upcoming gigs, the quote was seemingly everywhere. Ron McCarrell, at the time a marketing executive at the label, told Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin: "I remember turning the quote into a poster for record shops. And that was kind of the beginning of what led into the massive campaign for [the 1975 album] Born to Run." As Springsteen wrote in his autobiography, "There were ads for The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle in the newspapers and in major music publications; they all shouted, 'I have seen the future…,' and there I was, looking good. What a difference a day makes."

If this night and that review are crucial links that connect a young, struggling artist to the uber-successful, global superstar he would become, Jon Landau himself is a fundamental part of the chain. The rock critic and record producer (at that point he'd produced albums for Livingston Taylor and the MC5) would soon help Springsteen realize his breakthrough third record and go on to become his manager, a position he still holds more than 40 years later. More than that, he became, as Springsteen wrote in his autobiography, "the Clark to my Lewis." And that relationship was cemented on this pivotal night.

It's worth noting that May 9, 1974, was neither the pair's first meeting nor was it Landau's first Springsteen show. They'd met in Cambridge a month prior, in a moment of striking serendipity. If this scene were in a movie (and surely this moment will make the eventual biopic), you wouldn't believe it. It was before Springsteen's April 11, 1974 performance at another local venue — Bruce has alternately remembered it as Charlie's Place and as Joe's Place, and there's a reason he conflates the two: originally scheduled for Joe's, the gig was moved to Charlie's as a benefit show after Joe's Place burned down.

"I remember I was standing outside," Springsteen recalled in a 1978 King Biscuit Flower Hour interview. "I think it was in the wintertime, I was standing out there freezing cold. And [Landau] had written a review of The Wild, the Innocent, and they had it in the window — I guess to get people to come [to the show] or something. And I read it. He walked up to me as I was reading it, and said, 'I wrote that.'''

Springsteen biographer Dave Marsh was there, too; as he tells it in 1979's Born to Run: "Somehow, the fans standing in line didn't recognize him, but Landau did. Walking over, Jon asked Springsteen if he liked the piece. 'It's good,' Bruce replied. 'I've read better, you know.' Then Landau introduced himself. Laughing, they entered the bar."

The album review posted in the window called Bruce's second record "the most under-rated album so far this year, an impassioned and inspired street fantasy that's as much fun as it is deep." Foreshadowing their work together, Landau also wrote that Springsteen "ought to work a little harder on matching the production to the material."

Both Marsh and Landau first saw Springsteen in concert that night at Charlie's. Marsh wrote that Landau "left raving, not only to his Boston colleagues but to his fellow editors at Rolling Stone, where he made certain that The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle was named one of the seven best albums of 1973." Landau later told biographer Peter Ames Carlin, "The next day I got a call from Bruce, and we talked for several hours…. That was the beginning."

So a month later, "Growing Young With Rock and Roll" was no mere epiphany — it was, rather, a potent testament to a growing affinity. And when the Real Paper printed Landau's accolades, they wound up to be more important than any year-end list ever could be.

Detail of The Real Paper, May 22, 1974, as reprinted in Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future

"Springsteen does it all," Landau raved in his column. "He is a rock 'n' roll punk, a Latin street poet, a ballet dancer, an actor, a joker, bar band leader, hot-shit rhythm guitar player, extraordinary singer, and a truly great rock 'n' roll composer. He leads a band like he has been doing it forever.… Every gesture, every syllable adds something to his ultimate goal — to liberate our spirit while he liberates his by baring his soul through his music. Many try, few succeed, none more than he today."

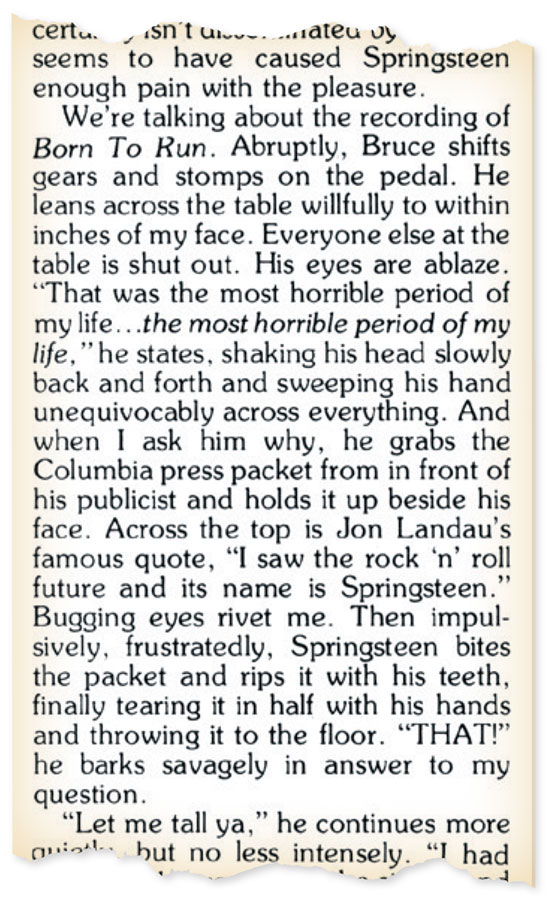

And Bruce was thrilled, right? Well… no. A resounding no.

"A bunch of jive."

"A kiss of death."

"The future ain't any damned thing.… Who the hell wants to read stuff like that?"

To be fair, Springsteen was responding to the marketing of the review, which occurred almost immediately, not the review itself — two very different things, as he would take pains to point out. As he said to Melody Maker's Ray Coleman in 1975, "Jon Landau wrote a great article — with his heart — and on that level it was very, very encouraging to me. At the time we weren't doing so good, and it helped me out with the record company."

Then the flipside: "But what they did with it was, like, a cheap publicity trick, and I resent it very much, that they used that quote. I guess good intentions were intended, but… the whole episode was a big drag for me, and still is. I mean, who wants to come out on stage and be the future every night? Not me."

So that was part of it — being called the future of anything is a lot to live up to. Then there's the fact that he had already been saddled with impossible expectations, proclaimed by his label and others as a "new Bob Dylan."

"I was in this big shadow, man, right from the start," Bruce told NME's Andrew Tyler in 1975. "And I'm just getting over this Dylan thing — 'Oh, thank God that seems to be fading away' — and I'm sitting home thinking, thank God people seem to be letting that lie, and phwooooeee 'I have seen… No, it can't be.… So like I'm always ten points down, 'cause not only have you got to play but you got to blow this bullshit out of people's minds first."

From Creem magazine, January 1976, as reprinted in Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future

One irony, in the couple of years that followed, is Springsteen decrying publicity in so many publicity interviews. But not only did he have to deal with the Future of Rock and Roll tag hanging around his neck, he also had to contend with those wondering if he wore it proudly — if he believed his own hype. In the Melody Maker interview, Coleman asked Bruce whether he considered himself "the future of rock and roll, as you have been described."

Hey, gimme a break with that stuff, will you? It's nuts, it's crazy. Who could take that seriously? The guy was sorta saying I wasn't just like a mixture of past influences, that I was like doing my own thing. CBS took this, promoted it real heavy, and I was like "SENSATIONAL!" Cheap thrill time!

You know, it was a big mistake on their part. They probably don't realize it, they probably think they're right and I'm nuts, you know. But it was a very big mistake, and I would like to strangle the guy who thought that up if I ever get a hold of him.

As Bruce described it to Tyler in NME, the quote and its use in advertising was suffocating — and he tried to stop it:

All the time, man, it's like… trying to find some room, man. Gimme some damn room. Give me a break, I was trying to tell these guys at the record company, wait a second you guys. Are you trying to kill me? It was like a suicide attempt on their part. It was like somebody didn't want to make no money.…

So immediately I call up the company and I say, get that quote out. And it was like, Landau's article… was really a nice piece and it meant a lot to me, but it was like they took it all out of context and blew it up and who's gonna swallow that? Who's gonna believe that? It's going to piss people off, man. It pisses me off.… It's like you want to kill these guys for doin' stuff like that. They sneak it in on you. They sneak it in and they don't tell you nuttin'.

Art vs. Commerce is not a new battle, and it's difficult to see it ever going away, but that's what Bruce found himself smack in the middle of: "All of a sudden you're something that money can be made with, you know?"

But figuring out how to deal with all this hype would serve the artist well, given how many later periods in his career would find him courting it, avoiding it, or riding it like a wave. Remember, the hype from the Landau piece came well before the Time/Newsweek cover doubleshot (October 1975) and posters declaring "Finally, London is Ready for Bruce Springsteen!" (November 1975), to say nothing of later omnipresent superlatives from "Blue Collar Hero" to "Poet Laureate of 9/11."

May 9, 1974 - photograph by Barry Schneier, from Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future

By his fourth record, 1978's Darkness on the Edge of Town, Springsteen had a change of heart and a "different attitude," as he told King Biscuit Flower Hour that year, calling his earlier reluctance to promote his records "silly." He described a more realistic outlook: "I mean, the records aren't going to like sprout legs and walk out stores and jump on the people's record players and say 'listen to me.'" But he still bristled about "rock and roll future":

The funny thing about that line… I don't know, I guess most people didn't read the article that it came from. And if they did, if they had read the article, it was not saying exactly what it seemed to say when it was used in the ad.… the article he wrote at the time, that means a lot to me…I think what he was actually saying was that the music that we were playing, me and the band, was a compilation of a lot of things, not just past influences and present, but also… future. Yeah, I think that was the intention of the line but… I guess somebody at the ad department was like, this is it!

Speaking with Elvis Costello in 2009 for Spectacle, Springsteen summed up the dual nature of Jon Landau's proclamation: "When that first hits you, you sort of half-agree… you go, hmmm, future of rock and roll, I kind of like the way that sounds! But then you go, but it also sounds like a shitload of trouble, man."

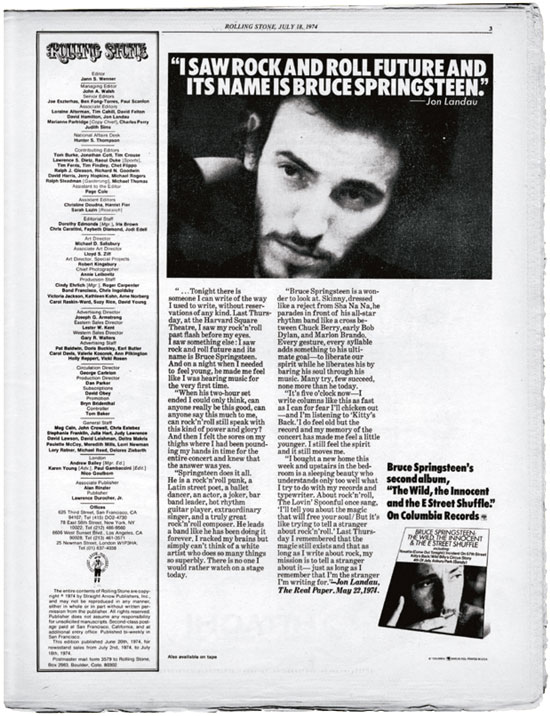

Columbia advertisement in Rolling Stone magazine, July 18, 1974, as reprinted in Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future

For all the troubles — and blessings — "rock and roll future" brought, it's particularly astounding that Landau was actually right. Not only would Springsteen become a superstar, he would impact the genre like few others and go on to become both a lifelong practitioner and elder statesman. Beyond the article's predictive powers, it led to the solidification of Landau's relationship with Bruce. Which may have been part of the writer's motivation, anyway. As Landau told Peter Ames Carlin in 2012's Bruce, "I was writing to myself, writing to the reader, and I was writing to him."

Marsh wrote in his 1979 biography, "The column did bring Springsteen and Landau together as friends. Shortly after the article appeared, Springsteen phoned Landau to thank him, and they became embroiled in a lengthy discussion. CBS still felt that Bruce had serious production problems that were preventing him from being successful. What, Springsteen wanted to know, did a producer do, anyway?"

Landau answered that question emphatically and in a very real way soon enough, as he came aboard to co-produce Born to Run (1975). From saving the day on that third record to co-producing numerous future albums, with practically a lifetime of management — to say nothing of books read, movies watched, and songs dissected together — it's simply impossible to overstate the influence of Jon Landau on the work of Bruce Springsteen.

If Bruce was dogged by the quote, don't think its author got off much easier. Decades after the fact, Springsteen's manager was still answering for it. Around the release of Human Touch and Lucky Town in 1992, Boston Herald journalist Steve Harris asked him, "What if somebody cynically came to you with this comment: 'I have seen rock and roll's past, and its name was Bruce?'"

Landau laughed. "I would hope that they're wrong! I still believe what I wrote all those years ago. My belief is that Bruce is so talented, so resourceful, so creative, that many, many years from now people will look back and they'll perceive that Human Touch and Lucky Town were albums that Bruce put out in the first half of his career. I think we're still in the first half of his career. That's how I see it."

From the vantage point of 2018, we can say: right again.

Soundcheck, May 9, 1974 - photograph by Barry Schneier, from Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future

Springsteen has had his own laughs with the "quote heard 'round the world," even decades on. At his 1999 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the artist had a chance in his acceptance speech to "return the favor" and took it: "I have seen the future of rock and roll management and its name is Jon Landau!" And ten years after that, in concert: "I have seen the future of the whole fuckin' thing, and it's Big Man Clarence Clemons!"

Most recently, in his 2016 autobiography, Springsteen revisited the Harvard Square Theatre events with a balanced perspective that has come with age and success. He recalls, "A man from Boston had seen the future of rock 'n' roll and it was… me." Writing that his manager-to-be "flipped his critical lid and wrote one of the greatest lifesaving raves of all time," Bruce describes its true thrust as well as anyone ever has:

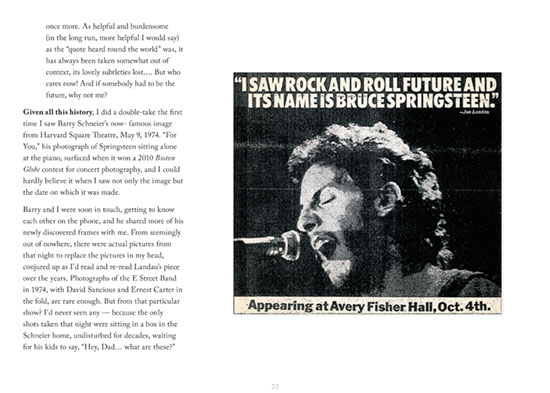

It was a beautifully written music fan's appreciation of the power and meaning of rock 'n' roll, the sense of place and continuity it brings to our lives, the community it can't help but strengthen and the loneliness it assuages. That night in Boston our band led with our hearts, and that's what Jon did. The famous quote came in reference to Jon's thoughts on the past, present and future of the music he loved, on the power it once held over him and on its ability to renew itself and exert that power in his life once more. As helpful and burdensome (in the long run, more helpful I would say) as the "quote heard round the world" was, it has always been taken somewhat out of context, its lovely subtleties lost…. But who cares now! And if somebody had to be the future, why not me?

Given all this history, I did a double-take the first time I saw Barry Schneier's now- famous image from Harvard Square Theatre, May 9, 1974. "For You," his photograph of Springsteen sitting alone at the piano, surfaced when it won a 2010 Boston Globe contest for concert photography, and I could hardly believe it when I saw not only the image but the date on which it was made.

Barry and I were soon in touch, getting to know each other on the phone, and he shared more of his newly discovered frames with me. From seemingly out of nowhere, there were actual pictures from that night to replace the pictures in my head, conjured up as I'd read and re-read Landau's piece over the years. Photographs of the E Street Band in 1974, with David Sancious and Ernest Carter in the fold, are rare enough. But from that particular show? I'd never seen any — because the only shots taken that night were sitting in a box in the Schneier home, undisturbed for decades, waiting for his kids to say, "Hey, Dad… what are these?"

I love that story, just as I love the story that these photographs tell, and the one Barry tells as he looks back on this time of his life, his discovery of Springsteen, his part in making the Harvard Square Theatre show happen, and his love of rock 'n' roll.

Not only do Barry's photographs get us closer to being a fly on that wall, but also they're simply beautiful photographs. He was creating them as a wide-eyed kid — a condition he remembers well and captures here — and he still creates them today, both selves bound by his enduring love of rock 'n' roll. Barry's eye and his voice, his perspective on that era and this singularly important night, I've found enthralling and invaluable. If I ever get that time machine, I'll look for Barry making these images in the wings. Until I do, his book feels like the next best thing.

- Christopher Phillips

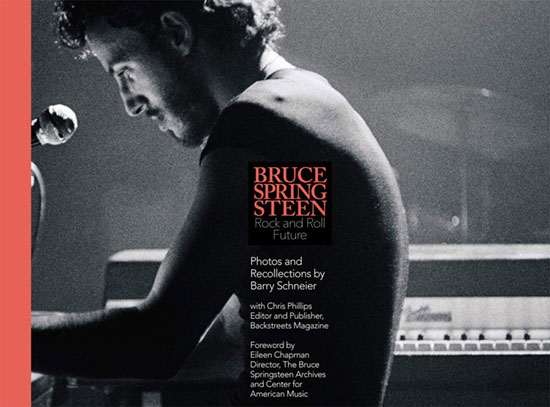

Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future is available in First Edition hardcover from Backstreet Records.

|