|

My friends at Backstreets have asked me to write a little something about my hero and friend, Charlie Watts, who died last week at the age of 80.

My heart is heavy with the loss yet full because of the talent, grace, humility, charm, wit, strength, and kindness CW spread throughout his life to his family, his fans, his friends, and his band. I am humbled and uplifted for the fact that I knew him.

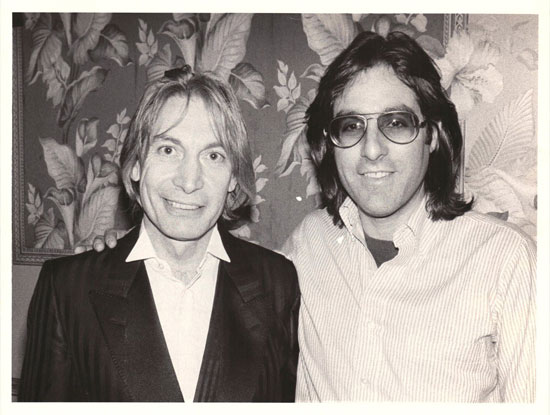

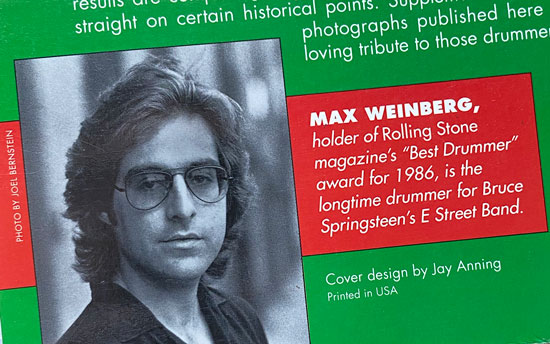

Charlie & Me. The long hair and my glasses (ugh) would suggest late ’80’s! He was not only a hero to me for his art, he was a real mensch!

I've talked a lot this past week about Charlie. I recalled that when I was a kid drummer in the '60s, a teen trying to find my way into the mysterious world of rock 'n' roll with a band — we didn't call them "garage bands," they were simply "bands" — we strivers would find ads for bands seeking musicians. And whether on the bulletin board of Rondo Music on Route 22 in Union, New Jersey (in my particular case), or in the Public Notice Music section of New York City’s The Village Voice (as pointed out to me some years ago by the great Modern Drummer interviewer Robyn Flans), those ads invariably included bands looking for a "Charlie Watts-type drummer."

Charlie Watts had become a genre unto himself!

The Rolling Stones back then were perfect for us somewhat-inept-but-hungry emulators. Beatles music was too hard; no one even attempted to play anything other than The Beatles' cover tunes. But, the Rolling Stones — blues-based — their songs you could pound out on the drums, and your excitement with the beat would cover up any of your insufficiencies.

I first saw The Rolling Stones on November 7, 1965 at what was then the Mosque Theater (now Symphony Hall) on Broad Street in Newark, New Jersey. My friend and I took the #77 bus down South Orange Avenue practically to the theater for the first show. We somehow paid three dollars for two second-row seats. When they were introduced, the girls' screams from the audience were loud—not as loud, perhaps, as The Beatles, but loud enough to send your heart into overdrive.

They opened with Solomon Burke's "Everybody Needs Somebody to Love," and a half-hour later Charlie Watts became indelibly etched in my heart and soul as the coolest cat I'd ever seen.

Nonchalant, seeming to throw it all away, Charlie held the drum chair with the aplomb of a hip jazz drummer who happened to find himself a founding member of what would become the self-proclaimed "World's Greatest Rock and Roll Band."

Why were they great? And still are? Of course, the songs, but even more than that, through the ups-and-downs, the angst, the absolute unique setup of a "democratic" rock 'n' roll band… they stayed together.

In many ways Charlie was not only the bedrock drummer of the Stones, as the New York Times put it last week, Charlie was the soul of the band. Proud to be there but somehow detached, as if looking in from the outside—in the way he referred to them as "them" — Charlie kept them grounded when the rock 'n' roll demons might have reached up through the quicksand and pulled them down.

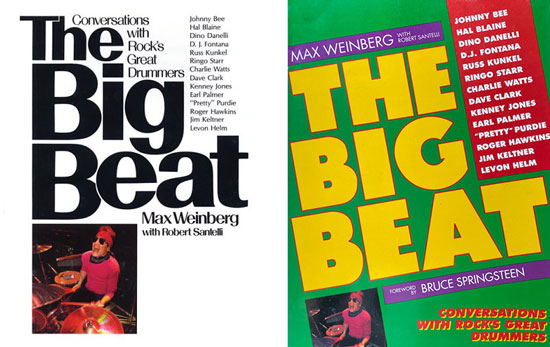

Backstreets has pulled the Charlie chapter from The Big Beat as a way to look back at a snapshot from some 39 years ago, when Bob Santelli (well known to readers of Backstreets) and I set out to ask the question why, not how, you play the drums. It was Dave Marsh's original idea after a friend of mine, author Harvey Kubernik, asked me if I wanted to meet Hal Blaine, the truly legendary L.A. session man. We met, and that conversation was the genesis of the idea of setting down their stories.

The first and second editions of The Big Beat, from 1984 (L) and 1991 (R)

As I said, Dave said I should do it. Now, you've got to know something about me — I was the guy who'd stay up all night to write the essay due in the morning. Mr. Procrastinator! But with a lot of encouragement from Dave, and the helpful writing tutorials from Bob, I set out to write a book.

Crazy, right?

I have to admit, it was a daunting proposition to sit across from the drummers I had so long admired, to be prepared to ask pointed, in-depth questions about their histories, and not come off as Chris Farley on SNL when he asked Paul McCartney, "…remember when you were in the Beatles?"

Fanboy that I was, I think back to sitting with Charlie, in the lovely tea room of his town house by the Thames River in London, as we talked drums and drummer history, mostly. It was my first one-on-one with him, and he couldn't have been more gracious and accommodating.

Throughout my life and career I've had so many of my childhood dreams and fantasies become real. One of those was getting to meet Charlie Watts. To become a casual friend, being invited to a Stones show when he was in town, seeing his Orchestra or Quintet or — how do you say it in -et? — ten-piece band was always a treat.

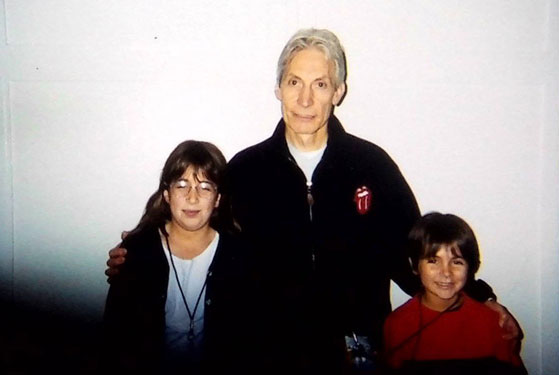

A wonderful moment for me a dad/drummer, my kids Ali and Jay, and my hero, Charlie Watts before his show.

Once he invited Becky, my wife, and me to see his five-piece at the Blue Note in New York. Small jazz club. You could tell he was having the time of his life playing the music, in his imitable style, that he loved so much. We were sitting stageside, and when the set was over, Charlie swept down from the drums, handed his sticks to me (which I still have), and fingered the lapels of my suit.

Oh, yeah, I always dressed up to see Charlie play. Respect. For me, it was like going to temple. As he inspected the material, he appraised, "Nice — worsted wool." But then Charlie bowed, took Becky's hand to lightly brush with a kiss, and in his oh-so-suave British accent said, "…and milady's in silk." Which she was.

What a moment!

Charlie Watts was royalty. Not in the monarchy sense, of course, but in the sublime manner with which he strolled through life, dapper as a dandy, with enough artistic talent — both on the drums and in visual arts — to not only become a genre unto himself but to truly earn the sobriquet of icon.

As I seem to have mentioned many times this past week, a New Jersey songwriter of some repute has on occasion observed, "There have been pretenders, there have been contenders, but there is only one (you fill in the blank)."

Well, in this case, I write in the name of Charlie Watts, who truly was a singular sensation.

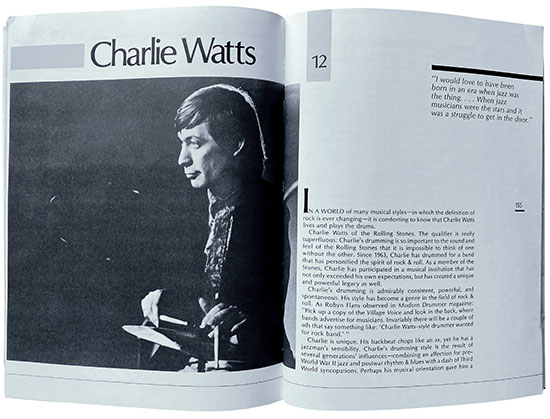

THE BIG BEAT CHAPTER 12: CHARLIE WATTS

IN A WORLD of many musical styles — in which the definition of rock is ever-changing — it is comforting to know that Charlie Watts lives and plays the drums.

Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones. The qualifier is really superfluous: Charlie's drumming is so important to the sound and feel of the Rolling Stones that it is impossible to think of one without the other. Since 1963, Charlie has drummed for a band that has personified the spirit of rock & roll. As a member of the Stones, Charlie has participated in a musical institution that has not only exceeded his own expectations, but has created a unique and powerful legacy as well.

Charlie's drumming is admirably consistent, powerful, and spontaneous. His style has become a genre in the field of rock & roll. As Robyn Flans observed in Modern Drummer magazine: "Pick up a copy of the Village Voice and look in the back, where bands advertise for musicians. Invariably there will be a couple of ads that say something like: 'Charlie Watts-style drummer wanted for rock band.'"

Charlie is unique. His backbeat chops like an ax, yet he has a jazzman's sensibility. Charlie's drumming style is the result of several generations' influences — combining an affection for preWorld War II jazz and postwar rhythm & blues with a dash of Third World syncopations. Perhaps his musical orientation gave him a super-defined sense of playing on the edge. His style is amazing, for he can hold the beat tight yet at the same time appear on the verge of losing it. But — he stays with it.

As musicians and personalities, the Rolling Stones have always been entertaining. Still, nothing was ever more important than their music. The songs have survived the test of time, and Charlie's contributions stand as examples of solid, expressive drumming. Consider the barrelhouse funk of "Honky Tonk Women," the galloping tom-toms of "Paint It, Black," the classic drive of "Satisfaction," his New Orleans-style drumming in "Rocks Off," the toughness of "Street Fighting Man" and "Gimme Shelter," on up to the more contemporary "Miss You" and "Start Me Up." Lifted by Charlie's drumming, Keith Richards's guitar playing and Mick Jagger's vocals, the Rolling Stones have consistently shown an ability to rock or roll in a variety of styles and have it all wash as Stones music.

I first met Charlie during the Stones' 1981 American tour. We talked a while when he and the band were in New York City, and we made tentative plans to meet again.

On September 8, 1983, I received a phone call from Charlie's London office informing me that he would be in London from September fourteenth through the twenty-first: Would I be available to come to England then? What a question! I flew to England to talk with Charlie.

He was in London to perform in two concerts for the benefit of England's Action Research into Multiple Sclerosis. At the suggestion of Ronnie Lane, the ex-Small Faces bassist stricken with this disease, Eric Clapton had organized this supersession. With Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and sessionman Andy Fairweather-Low on guitars, Steve Winwood on vocals and keyboards, Bill Wyman on bass, and Charlie, Kenney Jones, and Ray Cooper on percussion, it promised to be an incredible show.

Charlie invited me to the rehearsal the day before the concert, and even that was a remarkable event. Out from under the pressure of center stage, each musician seemed to enjoy a relaxation that drew out some very special performances. Seeing Eric, Jimmy, and Jeff together, on the same stage during that first concert was especially thrilling. Each a former member of the legendary sixties group, the Yardbirds, their passionate, soaring version of Eric's "Layla" was more than an encore — it was history in the making.

The next day, as we sat in his sunny parlor overlooking the Thames, Charlie served tea. As he had to be on stage three hours later, we had to be brief. With the television on in the background, Charlie leaned over to me and softly said, "I never do interviews. Can't stand them — bloody waste of time "

MAX: In that case, I'd like to jump right into this, Charlie, and ask you this: If there were any other time in history in which you could have lived and played your drums, when would that have been?

CHARLIE: Well, when I think of it, I would love to have been born in an era when jazz was the thing. I wish I could have been around when it was a struggle to get in the door, when jazz musicians were the stars. It must have been incredible. Not like today, when they can hardly fill a club. I mean, I would love to have seen Gene Krupa in 1941 when he had "Let Me Off Uptown" with Roy Eldridge on trumpet. God, that must have been something else. For two years every song was great. Though it was probably no different than it is today, with what they call rock & roll. You know, nowadays it's the singers and the guitar players. It must have been incredible to have had the trumpet player the star.

With the Rocket '88 band, you had the experience of playing with horns —

Well, there's one thing that happened the other day during the rehearsals for this benefit. I had a gig with [Stones aide and piano player] Ian Stewart's band. He has four horns and a guitar player. It's not like playing with the Stones, where you're following the guitar player and, obviously, the singer. Here you're following the horns, and when horn players play slow, they can play so slow — it’s all air. Unlike the guitar. It's unbelievable, really.

Did you find yourself having to change your playing to fit a horn band?

Yeah, sort of. I try to play with them. That's the art of a good drummer. Not that I'm a good drummer. A good drummer can play with anyone.

One element that helps make a drummer good is an ability to play in a variety of styles. With the Stones, you've certainly had to adapt to many different feels and styles.

The Stones are a good band to play with if you like that sort of thing. I mean, one minute you're trying to be D. J. Fontana, then you're Earl Palmer.

What was it like when you first hit the States?

Well, when the Stones actually got to tour America, I got to go to New York, and that was it. I never really wanted any more. In those days, the only way to get to New York was in a band on a cruise ship. I was lucky to get there right before Birdland closed. We first went to New York in nineteen sixty-whatever-it-was, and I think it closed about two years later. I saw Charles Mingus there with a thirteenpiece band. I also saw a marvelous Sonny Rollins period, where the band would stop and Sonny would just go on for hours. That was America. After that, I met Hal Blaine, but that was a whole other scene. He was a lovely man. He had the first remote-controlled garage door opener I'd ever seen.

I remember reading in a fan magazine in 1965 where you said your goal was to look like a black American jazz drummer.

I always wanted to be a black New Yorker. You know, the sharpest one on the street.

Did you have any one particular drummer in mind for a model?

No. It must have been a mixture of everyone, really. I suppose Tony Williams would have been one. His action looks so good; whether the notes are better than anyone else's, I don't know. I did see Gene Krupa at the Metropole, however. I never really liked his style. Everything he did was exaggerated. His cymbal would be level with his arms and his head would be level with his cymbal. It was very funny, I mean, instead of just throwing it away, every move was a big deal. But he was one of the best. Actually, I'd prefer to look at Buddy Rich rather than Gene Krupa. Buddy looks like he's giving it all away. I mean, how does he do it? When they talk about god-given talents, well, there you are. For fifty years Buddy Rich has staggered the drum world. He's played with every great musician, from Ravi Shankar to Charlie Parker.

You mention Charlie Parker; I know he's one of your great inspirations. You wrote a book about him, right?

Yeah. It was the story of a little bird. It was a kid's book. I just strung all the pieces together — the dates and things like that. It was just a bird instead of Charlie Parker. I was about twenty when I did it. The guy who published it used to do magazines called Beatles Monthly and Rolling Stones Monthly and Beat Monthly. It was when John Lennon brought out his book, In His Own Write. Well, this chap saw my book and said, "Ah, there's a few bob in this!" But of course John Lennon had a far greater appeal than me and Charlie Parker.

What is it about Charlie Parker that appealed to you then?

He sort of epitomized an era of my life. If I could have played an instrument, that's what it would have been. Even now, although I may only play him once a month, maybe six times a month, or not once in six months, every time I get to a good record of his, I still get that good feeling. Parker was just unbelievable — and dead at thirtyfive.

Charlie, how did you actually get started on drums?

Well, I had a banjo first. I tried to learn that, but I couldn't quite get the dots on the frets right. It drove me up a wall. So I took the thing apart. Luckily, it wasn't a really good banjo. I made a stand for it out of wood and played on the round skin part. It was like a drum, anyway. I played it with brushes. I got my first kit when I was about fourteen. Had a lot of fun with that. But I really taught myself by listening to other people and watching.

What were your early gigs like?

Well, I played jazz on weekends when I was working in the art studio. But I've done other things as well, you know, Jewish weddings, and that sort of thing. I never knew what the hell was going on. I'm not Jewish, you see. What you really need on those jobs is a good piano player. If the piano player's daft, you've got no chance. I don't care if you're Max Roach — you’ll only last a half-hour.

You really got your start in the burgeoning London blues scene during the early sixties. Can you tell me about that?

I used to play in a coffee bar two days a week, and it was there at the Marquee that I met Alexis Korner, who was really responsible for the start of R&B music in England. I remember I told him to turn his amp down! Ginger Baker used to sit in as well.

Ginger was such a powerful drummer with Cream. What did he sound like in the early days?

Ginger was an incredible jazz drummer; always in the best bands. He had a homemade kit; the first perspex [plastic] set I'd even seen. This was in 1960. He'd put his own fittings on, which were probably Ajax. And he used to have calfskin heads. They felt a quarter of an inch thick. He also had this really big ride cymbal with lots of rivets that he kept tightly buttoned down; it would not move an inch. One night when he was playing with Graham Bond, the organ player, I borrowed his kit. Ginger had been playing with Alexis, but that band folded. Anyway, this one night the Stones split the bill with Graham's band at a church in Harrow, and Ginger loaned me his set. But I couldn't play it, nothing would happen. I broke three pairs of sticks in one set! He had them set up so the angle was all wrong for me. It was total work. But Ginger could play them because his chops were so great. His wrists were amazing too.

How did you come to meet Mick and Keith in the first place?

Through Alexis, really. I'd been playing with Alexis before I met them. See, Alexis and Cyril Davies were the only ones really playing blues in London at that time. Cyril was a great harmonica player; he made a couple of very good records — "Country Line Special" was one. He and Alexis got together while Alexis was playing with Chris Barber, who had one of the biggest trad bands.

Can you define the term "trad"?

Trad is white revivalist traditional jazz. It was sort of like our Dixieland music. Very popular in the fifties. Anyway, Alexis would play the interval between sets and got the idea to form his own group. He teamed up with Squirrel, which was Cyril's nickname. Then Alexis asked me to join. I was away working in Denmark, but he waited for me to come back. After I'd joined up, we got the opportunity through Chris Barber, who owned the Marquee, to do the offnights. This was the old Marquee on Oxford Street, not the one now on Wardour. We played there on Thursday nights. After two weeks, Alexis held the record for people in attendance. Lots of musicians who were interested in that sort of music used to come. You'd get people playing bottleneck guitar, but if it wasn't a saxophone, I wasn't interested.

To get back to your original question, one night Mick and Keith came to one of our sessions. Mick did a few gigs with the band. It was quite hard to get singers; actually, it still is. We did a few things without really knowing one another. Mick never really liked the music we were doing. So they decided to get a band together on their own — or it might have been before I met them. Mick was at school then; I'm not sure whether Keith was at school or college. He might have been just roaming around. Brian Jones I met through Alexis as well. Brian loved the blues; he loved Elmore James. That scene became the only chance you had to play that music. It was a chance to talk about those records. Alexis was very knowledgeable. A lot of guys who played the Marquee went away and made their own bands up. At least, the next time I saw them they had their own bands.

You mean Mick and Keith?

Yeah, them and Paul Jones, who was with Manfred Mann. I'd seen Manfred Mann in clubs, not as an R&B band, but as a jazz band. You know, I used to play with Alexis and didn't really know what to play. He taught me to listen to blues records.

Whose records did you listen to?

Well, Jimmy Reed, for one. I think Earl Phillips, who used to play with Jimmy Reed, is a marvelous player. His drumming is the subtlest playing of that particular style. I mean, if you listen to Jimmy Reed, Phillips has everything, really. He has terrific dynamics and quite a bit of technique. Yet, he's not sitting there doing paradiddles all over the place. He does some marvelous triplet things. And his cymbal work is beautiful. Another guy was Francis Clay, who plays on Muddy Waters — Live at Newport. He is incredible. He plays Chicago style; the pickups are marvelous. He had this cymbal that curled up like a Texas hat. He played it around and around.

What you're doing looks like an old-fashioned dinner triangle — like "come and get it!"

It was a beautiful concept. Clay is a brilliant drummer. By anybody else, I suppose, it would be sloppy, but because it’s him, it's right on. He's whacking all over the place — sort of mad playing. Oh, it’s perfect, but I used to play more Muddy Waters than Jimmy Reed when I was with Alexis. In those days, Muddy Waters's tunes were like standards.

Did you leave Alexis at that point to join the Stones?

When I left Alexis, Ginger took over, and I went around with a few different bands. I was sort of between jobs, as they say. I used to play with three bands at once. You'd play with people you knew because they knew that you knew what song they were talking about. But Keith and Mick were looking for a drummer and asked me if I'd do it. So I said yeah. I had nothing better to do. Getting with them was just luck, really. I didn't expect it to go on; bands usually don't. So I kicked in with them. I was young, and you never see the end of the year, do you? I guess they became rather important, didn't they?

I've heard that the Beatles helped the Stones a bit in the beginning. Is that true?

I tell you what they might have done. I think John, because he knew Mick and Keith, or Mick and Keith knew him; I personally didn't know them that well. Obviously, Ringo I knew because drummers tend to gravitate toward each other [laughs]. John let them have "I Wanna Be Your Man." I think that was where the help came in. We used to see them about when they first moved to London. And we played with them at the Royal Albert Hall. That was the first time we played with them; the second time was at Wembley Stadium. It was incredible, man. Both times were for a New Musical Express poll. We went on first at Wembley because they had invented a "new" category called R&B for us, and the Beatles closed the show. We were so popular in London; we were like the "in" thing, really. We won the Wembley. I remember that you couldn't hear anything — it was just screaming girls. We went through that as well. I actually stood at the side and watched them. You couldn't really hear; the amps were so small and there were no mikes on Ringo's drums. Everyone was screaming.

Coming from a jazz purist background, how did you react to the audience screaming over your band?

I never understood it, actually, but I loved the adulation when we were on stage. After that I hated it. The days when you couldn't walk down the road without people running after you — literally. That was the most awful period of my life. I mean, it didn't happen to me that much, fortunately. I always kept away from that. I really couldn't stand it. It's quite incredible to go on stage and have that happen to you. Jellybeans getting thrown is really amazing. But that's part of youth, isn't it?

Having spent half your life performing with the same band, can you point to any changes that have had a significant impact on the Stones?

I think one of the biggest changes this band has faced was in terms of performing. We did this one particular tour of America during the mid-sixties. We returned three years later, and during those three years — because of groups like Led Zeppelin — everything changed. Suddenly it was that period where shows were incredibly long and there would be no audience reaction until after the number; then everyone went mad. It was really a concert. We'd always done shows for twenty minutes; now we had to play for two hours. We used to play a lot of times — when we were with other stars, if you like — on shows that were like revues. You only had twenty minutes because there were eight or nine other acts on the bill. Here we were coming from playing two to three hours nonstop in the clubs, to playing for twenty minutes a night. Then the kids would start shouting. We had a period where I never played more than ten minutes a night. It was every single night, but only for ten minutes — twenty minutes maximum. We never finished a show for about a year because someone would get hurt in the front row and we'd have to stop, or it would be chaos and people would run all over the stage. I can tell you — it didn't help my drumming much, but, you know, it was just part of being with the Rolling Stones.

Over the last twenty years, the Stones have recorded a vast amount of material. When you work that closely with people over such a long period of time, work patterns become quite established. When Mick or Keith present a song, how do you develop your ideas?

I try to help them get what they want. I mean, you do it a few times and you realize all your messing about ain't getting you nowhere, so you play it straight. Then, if they want something else, they'll tell you. It's very easy working with them, actually.

Do you find yourself referring to other recordings you've made?

Oh yeah, sure. You try not to when you're playing, but there are things I do automatically that are just part of me. You know, maybe a certain fill or a hi-hat thing. It all comes from playing with the same people, doesn't it? You just get used to them.

I've always found it interesting to hear what fellow members of your band — or any band, for that matter — think about the role another member of the band plays. Keith, for example, always refers to your unique feel — that you are the heart of the Stones.

Lovely! I've heard him say that about the feel. But I get the feel off of him, really. You know, when we play in those ridiculous places — stadiums and that lot — all I really hear is him. When I talk to Kenney Jones, he tells me about the Who's amps. Now that's equipment. Kenney has a monitor bigger than him for those gigs. I never worked like that. All I hear is Keith's amp, which is not that big. And I really listen to him all the time. If I wasn't able to hear Keith, I would get completely lost. It all comes from him.

Your drum sound seems to stay remarkably consistent from track to track and album to album, particularly your snare. How do you achieve that tuning?

For me, it's really how it feels more than how it sounds, somehow. I play the military-style grip, and the hard thing about that, when you're playing rock & roll, is to get the volume. The nicest sound is not to hit a rim shot like Krupa used to — you know, the high, ringy one that you hit with the narrow part of the stick — but to take the fat part of the stick and hit across the drum onto the rim. You'll get a thick sound, especially if the top head ain't too tight. Also, I don't play very loudly; the sound doesn't really come from the volume. It's getting the thing to hit right all the time. That's when I feel comfortable; when it's on and you don't even think about it.

One aspect of your playing and recording with the Stones was that you went from playing a boom-ba-boom bass drum pattern to a straight-four beat. Did you just fall into that or was it a conscious thing?

Yeah, that was conscious. I think the reason for that was, well, the old beat became unhip, didn't it? Unhip — I’m a bit too old for that. But the straight-four thing worked really well. It's funny you should mention that. I found playing that straight-four way very hard for me to do. I used to play the one and the three. To go straight through — I found that very hard to do. Keith and Mick would say, "Keep it going at the same volume," and you'd think, "Yeah, that's easy," and you'd start tapping your foot. But I found when I was going like that, the two and the four would be softer because of my left hand playing the backbeat.

It seemed Mick and Keith started writing songs that lent themselves to that feel, like "Miss You."

That was a very popular song, and it became sort of the "in" thing. I mean, there's a load of "Miss You"s, aren't there?

I'd like to try something, which is for me to throw out some song titles and have you —

— sing them [laughter].

Sure, if you like, but first tell me what comes to mind when I say "Satisfaction."

Oh, blimey! Jack Nitzsche, I suppose. He was standing in the corner of RCA's studio in Hollywood playing the tambourine. Phil Spector was there as well.

"Street Fighting Man."

God, it's Mick and Keith, really, that one.

One of my favorite songs is "Rocks Off."

Keith — that's all Keith.

How about "Beast of Burden"?

That's Keith too, really. That one came easy. It sounds odd but we just did it.

One or two takes?

Yes, it was as easy as that. It sounded so good; it's fun to play on stage. It's a lovely track.

"Paint It, Black."

That just fell, that tom-tom part. I mean that's a good example of what I mean when Keith plays a song — it was just the right thing to do. If I could have played a tabla, I might have put it on that track. Actually we ruined a marvelous pair of tablas trying to be Indians. You're not supposed to use sticks on them!

One of your funkiest tracks is "Honky Tonk Women."

I can see Jimmy Miller, the producer, playing the cowbell. One take, I think it was.

"Tumbling Dice."

Me and Jimmy Miller played it. Jimmy played drums on "You Can't Always Get What You Want." Did you know that? Jimmy Miller was the person in the studio who helped me an awful lot; he showed me how to do it. By that I mean he didn't stand over you, but he showed me certain things that would work and things that wouldn't, like fills and things. He didn't actually sit down and show them to me, but he used to love playing drums, so he'd play. Sometimes I couldn't play what he wanted, so he'd do it.

How did he help you?

He could hear songs better than I could. There's a whole period where Jimmy helped me out a lot without saying or doing anything. The result was that I began to realize I should work harder on my drumming, so I started to practice. Not on the drums, mind you, I practiced on my legs to keep my chops together. I can't stand practicing on the drums.

Keith said that if he doesn't see you or play with you for six months, suddenly you come back five times better.

Dunno 'bout that.

He actually said that.

Did he really? He is an incredible guy. Marvelous.

Would you say all you guys are close?

Yeah, I think we are, but we never see one another. You know how it is. At times you see them every bloody day, and then, when you're doing nothing, you might never see or hear from 'em. I suppose I speak to Mick more than any of the others because we talk about album covers or cricket or things like that. But sometimes I don't see Mick for weeks. There's a reason for that. I'll tell you — our band never would have stayed together. The Beatles seemed to be together all the time. I wonder if that had a bit to do with their breaking up.

I've been very fortunate in being able to get together with so many of the drummers I admire, but of course there are going to be some missing chapters. You knew both Keith Moon and John Bonham. Could you talk about them?

I was talking to Kenney Jones and I asked him what it was like going on the road with the Who and taking over Keith's seat. Of all the drum chairs to assume, to me that certainly would have been one of the most difficult. Keith's style was so flamboyant, I could not have gotten into that for a start. When we were working on Some Girls in Paris, Keith came over. It was an hilarious three days. He played with me in the studio, sort of stood behind me with all his tom-toms. I'd hired a couple of drums to make like I knew what was going on — you know, make the kit bigger. I never used them. But there was Moonie, a maniac really, always very charming, yet completely mad. I went out with him one day — the whole day — and it was the most hilarious thing. I always thought there was a limit, but he'd go on and on. You know, when the champagne's finished, let's go on to the brandy. There aren't many personalities around that were bigger than him. As far as his drumming, he was an innovator; he played with such style. He said Krupa was his big influence; well, you can see Krupa in him. It's a coincidence, really, that Keith and Ginger and myself are from the same area of Wembley. But I'll tell you what Keith Moon is — Keith Moon is what legends are made of.

Did you know John Bonham very well?

No. I met John a couple of times, that was all. He was an incredible player too, a wonderful player. His foot was the thing, for me, anyway. His foot was so strong. "Kashmir" and those lovely songs. I know Jimmy [Page] misses him. You can tell that even at the rehearsal yesterday. Me and Kenney — or, really, Ray Cooper and Kenney — were playing with him: we just knew that if Bonham had been there, he would have done what had to be done. You know, you need a drum about that big and be able to hit it so hard. Bonham — you won't get another one of him.

We've talked before about our mutual respect for Al Jackson. What would you say was his greatest talent?

Al Jackson was the best drummer of a slow tempo I've ever heard. It is very difficult to play that slowly. Also, I don't know anyone who could play as strongly as him. I've seen him play, and he could do everything.

The Stones' music goes on and on. As a band, you've faced many musical trends and created a large niche for yourselves in each. What do you think the Rolling Stones' greatest influence has been?

Well, I think what the band has done is helped put rhythm & blues in the place it should be.

Simple enough. Charlie, I have one more question; it's about something you mentioned before, that the art of a good drummer is the ability to play with anyone. But you also said that you don't think you are a good drummer. Why?

Well, I don't think what I do is particularly difficult. What is good, though, is that people look at me and say, "Well, I can do that." I like that. The drumming I do ain't hard, but drumming is hard when you take it a step beyond me, which is where you should be if you really want to be good. I ain't that good, and it's taken me twenty years — though I think the band I'm in is pretty sensational.

Max Weinberg’s September 1983 interview with Charlie Watts is excerpted from the book The Big Beat: Conversations with Rock’s Great Drummers, written by Max Weinberg with Robert Santelli, copyright 1984 Max Weinberg. Reprinted here with his permission. Additional thanks to Shawn Poole for his help with the OCR conversion

|