The European leg of the 2016 River Tour is now less than a week away. If you've been eyeing a show or two but don't yet have tickets, Steve Van Zandt's Rock and Roll Forever Foundation is continuing to offer ticket packages for shows in Europe, including not only VIP tickets (either prime seating or front-section GA) but also a meet-and-greet with Stevie before the show.

The European leg of the 2016 River Tour is now less than a week away. If you've been eyeing a show or two but don't yet have tickets, Steve Van Zandt's Rock and Roll Forever Foundation is continuing to offer ticket packages for shows in Europe, including not only VIP tickets (either prime seating or front-section GA) but also a meet-and-greet with Stevie before the show.

Click here for more information and to reserve tickets

The work of the Rock and Roll Forever Foundation is to bring the story of rock 'n' roll into classrooms — not just to music departments — in an interdisciplinary way. They provide resources for middle and high school teachers via a free curriculum called Rock and Roll: An American Story, with lessons and activities that engage and empower students in a time when arts education funding is being cut. Steven himself framed out the 40-chapter curriculum — spend a little time with it online at teachrock.org, and you'll quickly see the potential.

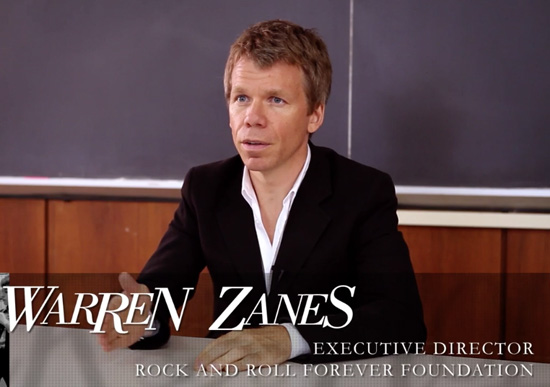

Given that this is one of the big hats Steven wears — along with musician, producer, actor, and disc jockey — we wanted to find out more about the work of the Foundation, and where money goes when a fan buys one of those ticket packages. To that end, Backstreets editor Christopher Phillips spoke with Rock and Roll Forever Foundation executive director Warren Zanes.

Dr. Zanes, like Van Zandt, is a man of many talents. You might know him as the guitarist from the Del Fuegos, or a solo recording artist; as the author of Petty, the recent, much-lauded Tom Petty biography; as an NYU professor; or as former VP of Education and Programs at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Steven lured Zanes away from the last of these, for his current "day job" overseeing the RRFF.

Phillips: As someone who feels like I've learned a lot about the world from rock 'n' roll — Apartheid and Vietnam are just a couple things that come to mind — the idea of bringing music into the classroom is really compelling. To not only teach the story of this artform that we love, but to have the music foster learning in other areas: history, social studies, English departments…

Zanes: Of course in "No Surrender" there's that line, "We learned more from a three-minute record than we ever learned in school." When I took this job with Steven, I said, "What about that line?" Because in a way, rock 'n' roll has always identified itself as apart from the institution. And here we are trying to bring rock 'n' roll in to the institution.

And he, like me, saw no problem with that. The truth of it is, we're trying to keep the story and the experience of rock 'n' roll alive. You run into an increasing number of young people who don't know a lot about its history and have fewer resources than Steven did when he was young, and I had when I was young, to get into music. So we're just trying to enrich the classroom as far as its music content.

It's interesting that you say fewer resources — in some ways there are too many resources: between YouTube and Spotify and everything else, there's so much music that can hit kids today in a wash, without any context.

Well, agreed. I would say young people are swimming in music. There is more content they can access than ever before, and they do access it. But that doesn't hold true for the classroom. Music in schools is generally left on the margins of the experience — in music departments. And not every school has one that is there to cater to every student. You can go K to 12 and not have much more than a couple general music classes.

But when you leave the classroom, you're swimming in music. And I think where we're failing young people, and we're depriving the classroom of some important energy, is in not looking at music from more perspectives than just playing it. So if there is a music department in a school, it's generally about getting an instrument into kids' hands and getting them some lessons.

Now, that is good. We want to support that. But imagine if we taught literature only to students who we think might become writers? It would be ludicrous. What we're doing instead with literature in schools is we're trying to make better readers. We're trying to teach history through literature; we're trying to give young people a better sense of the world through literature. Why don't we do the same thing with music? Why don't we teach young people to be better "readers" of this cultural phenomenon — popular music? But we don't. Instead they're swimming in it, and we don't have any classroom experience where they can become better at analyzing it and understanding its history, at understanding its power in modern life. Instead we just leave it to them. And I think it's one of American education's biggest missed opportunities that we haven't pulled music over into social studies and into the language arts.

And the richness of language in rock music, in popular music, is something you don't get at all in band class.

We did a dinner where there was a former congressman there. And he said, "Look, we all love what Chuck Berry did, but given the state of education, shouldn't we be focusing on reading and writing?" He said, "When I grew up, kids were memorizing poems." I said, "Make no mistake: kids are memorizing poems. They're called songs. They hear them on the radio, and they are memorizing stanza after stanza — but we're the ones not talking to them about that experience." There is a literary event taking place, when a young person finds a song, falls in love with it, knows every word, begins to analyze it on their own. The missed opportunity is that we don't engage with that experience as educators.

So Steven's project is really focused on all of the areas in the educational environment where we can be bringing music in. Not as a kind of break from academic study, but as a very integral part of academic study.

I guess for me, it's an easy sell — looking through the curriculum that's online, I immediately want to take this class. But has it been a hard sell for other people who see music as something more tangential?

You put your finger on an interesting part of what we face, in bringing this into schools. And that is: we don't face resistance. I remember working at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I saw the last administrator who was reluctant to take rock 'n' roll seriously. I watched him retire, and I've never seen one of those again. We are at the point where everybody has grown up with this stuff, and formed their identities in relation to it. So we have that kind of spiritual support.

The problem is, to effect change in education is very, very difficult. So the problem now isn't administrators who say "Rock 'n' roll shouldn't be in the classroom!" The problem now is getting teachers to teach their material in a slightly different way — one that folds music into their course of study.

One of the reasons it's hard to effect that change is that teachers have too much on their plate, and they have very little time to modify what they've been doing for ten or 15 years. They're not resistant to the idea, but they're overtaxed. So part of what we do is not just to develop materials to help teachers bring music into the various disciplines, we need to do professional development events where we can show teachers how to do it. So if you are doing a unit on civil rights, here are some inroads for you. If you are looking at the growth of the suburbs in post-war America, here are some inroads. If you're looking at the '90s or shifts in the economy around the time of Reagan, here are some inroads. But they definitely need to be shown the connections between what they'd be teaching already and what we have that's music-based.

How much of the curriculum is envisioned as a stand-alone class, and how much of is a pool of resources, materials to bring into what's already being taught?

We see it as a situation in which both should be happening simultaneously. We have the ideal, which would be the teacher who can take a semester and go beginning-to-end through this curriculum. But we also recognize that very few teachers have that semester where they're looking for an open elective and can do it. So more often than not, it's as I described: they're looking at post-war America, what happened in the time of the Baby Boom, and they're looking for additional materials and new ways to look at a subject that they've been teaching already. And so they go to our site, and they pull some activities out, they pull some resources out, and we begin to get them in that way. What we've seen is that teachers who become users by pulling facets out come back and start doing whole lessons. And they build. So our job is to convert them — and the conversions have been successful.

So you see that happening? Teachers adding one thing as a resource, finding that it connects with the kids and helps the discussion, and they come back for more? That's a system that works?

Yes. And the most persuasive piece for them is increased student interest. When you bring popular music into the classroom — even if it's something that predates them, even if it's something that their parents grew up on — there's a kind of empowerment effect where young people feel, "Oh! This is as much mine as it is the teacher's." And with that heightened feeling of ownership over the material, you have increased engagement. And that's what teachers are after.

I teach at NYU — we do a class each fall that uses materials from Steven's curriculum. And it's the same problem there: you know, you see students in the back row drifting off. But the closer you get to something that they feel they've got an investment in, the more they perk up. When you're teaching Jane Eyre, or Chaucer, they know it's not theirs.

How did you initially connect with Steven to work on this?

He hired me away from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Here's a guy who I knew from the music he'd made, but just as much I knew his radio show. And on the radio show, what I heard was really an organic educator. I think that's what makes his radio show special: he's always teaching. That really appealed to me. He's not an educator born of the classroom; he's an educator born of the fact that music, and its related cultural products, changed his life, and he's passing that along. So when he approached me, that's what I saw. That's the right guy to do the project he's describing to me. Because he's always doing it anyway. In his personal life, you can see him — he really doesn't stop. I've interviewed lots of artists in various contexts; not all of them fit that description.

Who else does?

I would say Elvis Costello fits that description. Robert Plant fits that description. There are guys out there who are so soaked in the cultural stories around popular music that they are naturals to carry the message forward. With Steven, I think he feels compelled to do it. He does it in the radio show, but he also does it in a conversation on the street.

This may be more of a question for Steve, but I'm interested in your perspective: Do you know what sparked this idea in him? Was it doing the radio show and having the sense that, yeah, these are things that people need to know?

I don't know the exact answer to that. I think it relates to what I was saying: that this is just how he thinks. My sense about him was that if you don't know this story in a deep way, your quality of life isn't what it could be. There's so much good in this, whether it's young people feeling empowered after the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan, or the way that the music connected up with civil rights. Like, if you don't know that's possible? Your life is diminished because of it.

So when the guy who did Sun City is himself a product of what he saw in popular music — its capacities, what it could do, the change it could effect — he really took it and did something with it. More than just an intellectual idea, he turned it into a practice.

And I think that's what he's doing here: looking at education and saying, it doesn't have to be this way. It can be better. And here's a strategy for making it better. This will help students, this will help teachers, this will increase engagement and show people that in the classroom, people can undergo these positive changes.

Who develops the curriculum?

He framed out that 40-chapter history. And he's involved every step of the way. You know, behind every idea he has are three more — I'm sure you know this about him just from your years of covering the Bruce "family." He's always got something.

Then what we're doing is sculpting. We need to think about, okay, these are all good ideas, these are all viable ideas, these are all important ideas. But we need to package them for the classroom, knowing that not every teacher is going to have the same grip on the history of popular music, and not every classroom is going to be the same. Some are inner-city urban, some are rural. So we need to take the ideas and give them shape so that we can maximize the possible users. And we know the practicalities of the classroom — what's possible, what isn't — and we can also shape the lessons in relation to national standards, Common Core standards. There are some practicalities that you only learn by knowing the world of education. That's where his team comes in. It's definitely a team project.

Warren Zanes (front row, third from left) with Steven Van Zandt, RRFF staffer Adam Rubin (front row, far left), and a group of pilot teachers from around the country

How big is the team?

Right now we're in something of a transitional phase, but small — going between four, five, six…. Small. And then a lot of our strength comes from partnerships. We have a partnership with NYU, we have a partnership with Scholastic, ABC News. And then archival partners, like David Peck's Reelin' in the Years, which is one of the biggest in music film and video; Barney Hoskyns' Rock's Backpages is a partner.

When we create a lesson, we want students to see primary and secondary sources. When they look at the Beatles lesson, if from Rock's Backpages they can see one of the very early reviews of the Beatles, before they became the chart-topping sensations, they can begin to see the music in context. To look at images of Hendrix or read reviews of Hendrix before he came and played Monterey, it helps you see: Wow, when Hendrix first arrived, people didn't know what he was. He wasn't behaving like Otis Redding. Or even Little Richard. This was some new hybrid that had not yet been witnessed. And then to go back into the historical resources, you can see they didn't know what it was.

Which is also a very interesting lesson in journalism.

A lesson in journalism, a lesson in history. These kids are reading history books where everything is taken as an objective fact that seems as obvious as the day is long. And it's like, that's not how histories come into formation. The chaos that becomes shaped into a history… if you can get students to begin to have a critical relationship to their history books, that's a pretty heavy moment.

Hopefully when they see enough primary sources and enough historical resources, they can begin to get a little more sophisticated and even question their history books. Which is a moment of empowerment, where they can raise their hand and say, Isn't there another way we could understand this? And then, next thing you know, they're going to be in graduate school.

So as a non-profit — I heard Steve stress that there's no government funding here, so I'm curious how this works, and how crucial individual donors are. When fans buy one of Steven's ticket packages for the River Tour, where does their money go?

First of all, one place their money is going, they're going to invest in this Teach Rock curriculum, ensuring that it's free to teachers. No money changes hands: students don't have to pay for it, teachers don't have to pay for it, schools don't have to pay for it. Given the caliber of the resources, that's a fairly unusual situation. But in order to create it all, money is required. In some cases there are licensing issues, there are definitely staffing issues, there's the website, the work through partners like Scholastic — it all costs money.

But the end goal is to deliver something that has a kind of academic rigor to it, that has a high level of energy to it, that connects to young people's lives, and does not cost anyone anything to use. So if there's an underserved inner-city school, and there's a private school, neither of them pay.

Does any funding come from Scholastic or other partners like that?

No — in fact, Scholastic is a for-profit, so when they do something for us, it is a service that we pay for. Their expenses have to be covered. They give us a very fair but appropriate deal. So the way this gets paid for, so far, is all through private individuals. It's the person buying that ticket doing the meet-and-greet, or it's high net-worth individuals giving substantial gifts. But thus far there's not any government funding behind it, and there's not any corporate sponsorship. Not that corporate sponsorship is out of the question, but thus far it's just been individuals seeing the worth of this endeavor and putting their money where their mouth is. You don't see a lot of this. A lot of non-profits hire people to do grant writing full time. That hasn't been our case. The idea behind this, and the quality of the materials — once people get to know those two things, we find a lot of support.

Can you tell me a little more about your initial connection with Steven, and what led you to make that jump from the Rock Hall?

I did a live interview with Steven when I was there. One thing I've learned in doing interviews was, you can often find everything you need for interview content in the early part of an artist's career. Often times, before they become famous is a world of riches. And so with Steven, we talked a lot about how he got into music in the first place, talked about playing in what were then considered "oldies acts," and what he learned there, bands before he joined the E Street Band, and it was, for me, a really fun and informative interview. I think every artist likes to talk about stuff they're not accustomed to being asked about. The topic really wound up being "The Education of Steven Van Zandt."

At the end of this, he just said, "If you're ever thinking about leaving the Hall of Fame, just let me know." And I considered that a great compliment, coming from a guy who knows his history like he does.

Then he called six months later. And at that moment, I had sitting on my desk a contract from the Hall of Fame. You know, I love the Hall of Fame as a museum in Cleveland. But I often felt like the induction process was a distraction. For the work I was doing — I understand where it fits into other people's lives, but for me, I was an educator based at a museum, trying to do educational programs, trying to do live-in-the-museum programming, and the inductions would often get in my way.

Like when I reached out to Leon Russell and said, "I want to bring you into the museum to do a live interview, talk about when you were a member of the Wrecking Crew, talk about when you had Shelter Records with Denny Cordell..." What he was seeing was that he hadn't been inducted yet. And he wouldn't come. In cases like that, it's a shame — more people should know how heavy a guy like Leon Russell is. But he was just seeing the induction process. That could get in the way.

With Steven, I was like, wow, here, instead of people seeing an institution, they're going to see this guy. And he's got a reputation, and it's positive. And where the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction process could get in my way sometimes, I thought Steven's presence and how people viewed him would actually open doors. So I made the choice to leave the Hall of Fame and go with him, and I think I was right.

Right: Steven Van Zandt visits a 12th grade seminar called Rock and Roll History of Postwar America," structured around the Rock and Roll: An American Story online curriculum, at NYC's East Side Community High School

Right: Steven Van Zandt visits a 12th grade seminar called Rock and Roll History of Postwar America," structured around the Rock and Roll: An American Story online curriculum, at NYC's East Side Community High School

What appealed to you about what Steven was doing, the Foundation itself?

The most important thing to me was that he was looking at teaching music not as a means to get instruments into kids' hands — he wanted that to be an effect of the approach he had in mind, but he was seeing that this should be taught in an interdisciplinary way, that it should be in social studies, in should be in language arts. That's a very good intuition; I think that's exactly what needs to be done. His educational model was the one I already believed, in my experience up to that point, was the crucial move to make.

And that does seem like an important distinction to make — there are groups working to help music departments, with instruments and support, and there's a great need for that. Little Kids Rock is a prime example. But the Rock and Roll Forever Foundation has a different mission.

If you bring instruments into a school but the belief in what music means and what it can do in a young person's life is not there, it's a malnourished situation. They might have those instruments, but they might not have the kind of philosophy that will help them to make the best use of those instruments.

If, however, you've got young people in a classroom looking at American history, and they go into the 20th Century, and the radio is introduced, and recording culture is introduced, and you start to see the entrance of the jukebox, and the wars happen…. characters like Hank Williams, and Elvis Presley, and James Brown are tied into this story…. You're going to be showing young people something very real about American life: music has always been a part of it, at a particularly high level in this country. And if you teach that way, they are going to get to a point where the idea of making music is going to come to them.

Hopefully at that point, there is a music department that has instruments, and has people capable of helping young people learn how to play them. Then all the pieces come together. But if you're only doing music in music departments, to me it is an environment suffering from a kind of spiritual malnutrition. The teaching environment does not reflect what American life is really like. American life is really a musical life.

And that's really reflected in what I've seen of the curriculum, and its breadth. I was glad to see that you go up through hip-hop. I imagine that music's connection with earlier portions of American history might be easier to incorporate into what's already being taught, but I think of the inspirational aspects of what you might learn from a hip-hop segment. People who don't have instruments, what have they got? They've got turntables, and records. And what you can do with what you've got: this explosive new art form comes out of that. There's something very inspiring and very American about that, not to mention direct relevance to current events and the music that gets radio play.

If you look at the last couple years in this country, there's been a lot more for teachers to look at in terms of race relations. If they want to start to look at that hot issue — which is a hard one, because it's so close to the present, and the closer it is to the present the harder it is to bring into the classroom — but if a teacher wants to start to look at race relations in this country, hip-hop, post-soul, black music, these are going to give teachers a number of angles from which to approach questions of contemporary race relations.

Too often the story that gets told is, there was this guy Martin Luther King, and he was a part of this civil rights movement. And it happened, and change took place. And thank God it happened. But there's not a lot of looking at post-civil rights America. And that's really what's needed. For any teacher who wants to explore contemporary race relations, they're going to have to look at both the successes and — I wouldn't say the failures of the civil rights movement, but all that civil rights could not do. So many facets of black life didn't change.

So when we look at Curtis Mayfield and Superfly, and Marvin Gaye's What's Goin' On, and the first Stevie Wonder records where he's working outside of the production model that Berry Gordy established, they're all looking at black life post-civil rights. Through the music you can begin to look in a very frontal way at this stuff. We share things like graphs that show you how the population changed in the inner cities in the early '70s — there's a very physical way of seeing what the "white flight" was. It's not just a term; here are the numbers.

Now let's go back and listen to the music. Kids will begin to put it together, and then okay, you begin to see where hip-hop comes from. The message was not without roots in early-'70s funk. It comes from that, then the technology shifts in part because, as you say, in those eroded inner cities, you didn't have music programs and instruments. And so there's a making-do. What do they have? Turntables. What's their dance floor? Cardboard on the street. What's their canvas? A subway car, and a can of spray paint. And this full-blown artform emerges.

When you mentioned What's Goin' On, I was reminded of a book by Nathan McCall called Makes Me Wanna Holler — it's a memoir, I read it probably 15 years ago, but it really stuck with me. The author came of age in the '60s, committed some terrible crimes and went to prison, but wound up turning his life around and went on to be a newspaper journalist. And the turning point for him was hearing What's Goin' On one night — he describes it as an epiphany, the way that record clicked with him and opened up his horizons.

It's interesting, like when you've described being hit by Born to Run, these kinds of epiphanies that take place for us as listeners are really common in music. I think everybody has these moments of awakening, particularly around adolescence. When you think how many people have had that experience — it's common.

How many people have had that experience through paintings? Even through literature, it's more rare. This cultural form that does this to us, and it's the thing that throughout our lives we cherish, that we're not studying it — the more you think about it, the more it seems like an egregious mistake.

From the outside, what you're doing seems like a wonderful thing to be a part of. I wonder if sometimes it feels like pushing a rock up a hill.

Well, it does, for the very reason that I told you — not because people think this is a wrong-headed idea, but because it's very hard to effect change in education. Look at the disciplinary models, just the way they set things up: here's music and art on the outside, here's English…. We've been doing this for not decades, but centuries, without a lot of critical thinking around the validity of that model. But it's very hard to make change. Same at universities. There's so much work to be done that it's hard to step back for a moment and say, maybe we should change the structure and the educational approach.

There are a lot of radical, good ideas out there — but to effect change and bring those ideas into actions, that's tough. Anyone doing the kind of thing where you're trying to heighten the arts experience and bring the popular arts into the educational sphere? Yes, you're moving a rock up a hill.

But you've got kids in school, right? I'm sure from your perspective it looks one-hundred-percent worth it. I've got two boys, 11 and 13 — I know I want this in their history books.

Click here for River Tour ticket pages that support the work

of the Rock and Roll Forever Foundation