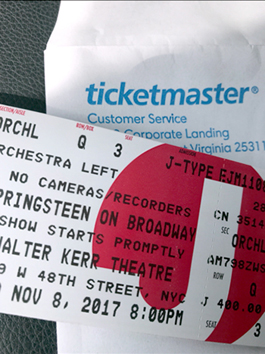

In this brief lull between ticket sales and the curtain rising on Springsteen on Broadway, it's a good time to take a closer look at Ticketmaster's Verified Fan system, the method used to sell tickets for 79 performances at New York's Walter Kerr Theatre.

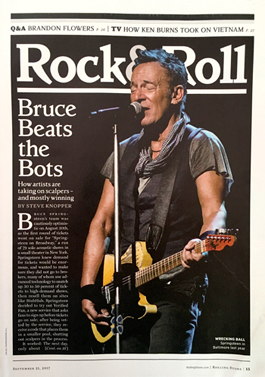

Beating the scalpers is what Ticketmaster's Verified Fan system is purportedly all about. After years of fans calling for action to combat scalping, the spawn of bots, and system failures, Ticketmaster tried something different. And it had an effect. Is everyone happy? Of course not. Considering the supply and demand for these shows — one source tells Backstreets that as many as 300,000 people may have signed up for verification — it was a given that many dedicated fans would get frozen out.

Whether 1998's Come Together benefit for the late Sgt. Patrick King or numerous nights at Madison Square Garden, a tough ticket is familiar to Bruce Springsteen fans. Performances like those have sold out within minutes of going on sale, a story that has been told and retold all over the world (a tip o' the cap to our friends in Ireland). But that was not the case with Springsteen on Broadway, probably the hardest ticket to come by in recent times. So let's consider what the new system did and did not do to give Springsteen fans a fighting chance.

Episode II: Attack of the Bots

Since the mid-'70s, scalping has consistently posed an obstacle for any prospective Springsteen concert-goer. Once online sales became the norm, that obstacle grew exponentially. It's one thing to find a few non-fans paid to stand (or sleep) in line in front of you; it's quite another to have automated bots snap up thousands of tickets faster than human fingers can type.

Since the mid-'70s, scalping has consistently posed an obstacle for any prospective Springsteen concert-goer. Once online sales became the norm, that obstacle grew exponentially. It's one thing to find a few non-fans paid to stand (or sleep) in line in front of you; it's quite another to have automated bots snap up thousands of tickets faster than human fingers can type.

According to a recent Rolling Stone article, "many [brokers] use advanced technology to snatch up to 30 to 50 percent of tickets to high-demand shows."

"It's been a cat-and-mouse game for 20 years," a 25-year ticketing executive (T.E., who requested anonymity) tells Backstreets, "since they flipped the switch on Ticketmaster.com." Now, he says, "it seems they might have finally figured it out. At the end of the day, the [new] system was set up to put tickets in the hands of fans, and it looks like that's what it did."

Both Verified Fan onsales took more than an hour to sell their respective allotments. In both cases, around the one-hour mark, some prospective buyers who'd been on "standby" were given the opportunity to enter the queue. Had Ticketmaster's Verified Fan system not been in place, scalping bots would have ended the onsale within minutes: huge blocks of tickets would be in scalpers' hands. Unless you've only bought stadium tickets, you've surely had that experience of a ticket sale ending so quickly it made your head spin.

Though Verified Fan has a dubious name, it means to weed out resellers and scalpers (automated or not), not to anoint fans. As Ticketmaster's David Marcus noted on E Street Radio recently, the only thing that Ticketmaster sought to verify throughout this process was the group of registered individuals who were likely to use whatever tickets they bought. Meeting that criteria, and that criteria alone, got you into the code lottery. This wasn't an attempt to identify or rank the "biggest," "best," oldest, or most loyal Springsteen fans. Though that may not have been made clear by the name, it was, at least, clearly stated online:

Ticketmaster #VerifiedFan was designed to separate actual, human fans from bots and scalpers. The system aims to thwart bad actors who are in the business of taking away tickets from fans just so they can resell them. Our technology analyzes every registrant to make sure they are real people interested in going to the show.

In onsales (August 30, for October-November performances; and September 7 for the December-February run), algorithmically lucky fans holding codes purchased approximately 77,025 Springsteen on Broadway tickets (a figure derived by multiplying the Walter Kerr Theatre's 975-seat capacity by 79 scheduled performances; bear in mind, however, that a small number of tickets may have been held back for drops, Tony voters, etc.).

While sky-high secondary prices have merited plenty of outrage and ink, to date no more than about four percent of that approximate total has appeared for resale on legal-scalping sites such as StubHub (owned by eBay), Ticket Liquidator, Vivid Seats, et al. Moreover, it's impossible to determine how much of this "inventory" is real; does a ticket exist behind this listing or that one, or is it a so-called "speculative" offer? With no significant external regulation in sight, these empty offers continue to tarnish the ticket-reselling industry.

Furthermore, even the exorbitant, hyper-inflated resale prices for Springsteen on Broadway are likely to fall. Typically, the supply-and-demand factors that work in the scalpers' favor begin to reverse rapidly as an event draws closer. Sometimes, if the timing is right, one can beat the scalpers at their own game, and for a song. (On the Rising tour, one of us paid a scalper five bucks.) That serendipity may not occur as frequently on Broadway as it does on the road, and you'd be ill advised to buy tickets on the street for this one in particular (caveat emptor any time you're not buying from the primary source). But the recently announced Springsteen on Broadway SiriusXM Sweepstakes is a good reminder that opportunity doesn't end when the onsale finishes. Whether it's a contest, ticket drop, or fan-to-fan exchange, hope remains alive that at least a few more dogged fans still can get in the door.

Wishful thinking aside, we can't recommend StubHub, Vivid Seats, and the like. We're allergic to their hallmarks, namely jacked-up prices and the questionable reliability of those who traffic there. But while scalping is anathema to us and to many fans, we admit that a secondary market for tickets isn't inherently evil. BTX, after all, is a secondary market, though one where we insist on face-value exchanges only. And other than profit, there are legitimate reasons to move tickets from one's hands to another's.

The right to a chance

Given the relatively low number of tickets available for a run of special performances in a theater as small as the Walter Kerr, it was inevitable that most fans wouldn't get to buy tickets. Fans frustrated that they didn't receive a code or even standby status may take solace that they did have a chance (chance being the operative word); it's just that their chance didn't come at 10 a.m. on the day of the sale, as we're accustomed to.

Given the relatively low number of tickets available for a run of special performances in a theater as small as the Walter Kerr, it was inevitable that most fans wouldn't get to buy tickets. Fans frustrated that they didn't receive a code or even standby status may take solace that they did have a chance (chance being the operative word); it's just that their chance didn't come at 10 a.m. on the day of the sale, as we're accustomed to.

The Verified Fan system not only weeded out bots, but also effectively served as a lottery, randomizing onsale access to create smaller pools of qualified individuals. We've been here before; mail-order lotteries for Springsteen ticket sales occurred as far back as the original River tour. (Even as late as 1988, there was at least one mail-based lottery.) And in this age of internet sales, narrowing the on-ramp in advance and throttling the sale surely helped Ticketmaster stay up and running; previous onsales for high-demand events have wreaked havoc and brought the site to a crawl, vexing consumers each time. The Verified Fan system succeeded in keeping the overwhelming majority of tickets available for purchase by individual Springsteen fans, without overwhelming the system.

Which is still not to say it was entirely fair.

One flaw of Verified Fan revealed itself in the second onsale. That pitted ticketless fans not necessarily against scalpers, but against fellow fans who had already scored tickets for the first run. Sales of tickets in the second round were limited to two, regardless of whether someone had already purchased tickets in the first.

"My biggest issue with this is," says T.E., "given the high, high demand and the relatively low supply, they should have allowed two tickets per person, period. They should have said to everyone in the first round, 'Okay, you're in — you're not eligible for round two.'"

"Objectively," he continues, "if this is about fans over brokers, they hit their objective. But I also think the goal should be to get tickets in the hands of as many fans as possible."

Anecdotally, it appears that previously unsuccessful accounts may have been prioritized in the second onsale's code lottery, but we don't know that for a fact.

What's in the box?

We also don't know exactly how the Verified Fan algorithm works. We can be relatively assured that that there are no Taylor Swift upsells here; again, from Rolling Stone: "While Springsteen's ticket-buyers are picked purely by algorithm, Swift's fans can increase their chances of scoring tickets. Their place in line is determined by 'boosts.' Those boosts can be earned by tweeting and streaming — and also by buying merchandise."

We also don't know exactly how the Verified Fan algorithm works. We can be relatively assured that that there are no Taylor Swift upsells here; again, from Rolling Stone: "While Springsteen's ticket-buyers are picked purely by algorithm, Swift's fans can increase their chances of scoring tickets. Their place in line is determined by 'boosts.' Those boosts can be earned by tweeting and streaming — and also by buying merchandise."

Nonetheless, this "pure" algorithm remains a black box. That it's effective in stiff-arming the brokers is a tremendous accomplishment, but when it comes to giving thumbs up or down to individual fans, we don't know exactly what it takes into account.

"If you live in Philadelphia and have mainly bought tickets for Springsteen's Philly arena shows — that isn't a Ticketmaster venue," T.E. points out. "Buffalo is Tickets.com. How did that affect verification?" We may never know, especially if it means publishing information that scalpers could incorporate to make their own profiles more conforming. Maybe that's okay.

As it stands, however, Verified Fan only encompasses the initial purchase of tickets; it's not an end-to-end solution. Once tickets are in hand, nothing in the system prevents them from being resold. With prices so high on the secondary market, even diehard fans find themselves enticed to sell. Make no mistake: not every resale listing is from a professional scalper. It has become more tempting than ever to weigh the opportunity cost of witnessing a show.

Several entry systems pointed to as alternatives would likely be unworkable when it comes to Springsteen on Broadway. When Springsteen played St. Rose of Lima in 1996, tickets were limited to Freehold residents only; they had to show a credit card and driver's license to prove it. But on Broadway, an additional hoop like that could be a non-starter. "Most of the employees are union in these theaters," says T.E., "and that likely limits what they can do."

Paperless ticketing (also known as Credit Card Entry — essentially, an electronic ticket stored on the purchaser's credit card) might seem like an obvious solution to deter scalping. Sadly, because of New York's anti-paperless laws, it's off the table.

So shut-out fans are inevitably disappointed, questions remain about the algorithm, and further steps could be taken to counter the scalping epidemic. Nevertheless, Verified Fan has moved the ball forward considerably in getting tickets directly to fans. And to date, Ticketmaster has put its money where its mouth is, keeping Springsteen on Broadway tickets off its own secondary market, Ticketsnow.com (part of the Ticketmaster/Live Nation network).

"If they allow resale on Ticketsnow," says T.E., "that's when shit would hit the fan." In other words, it's been a long time comin', Ticketmaster, and now, apparently, it's here. So, please listen to what the man says, and don't fuck it up this time.

- Christopher Phillips and Shawn Poole reporting - ticket photo by Nancy Calaway - special thanks to Jeff Calaway, Erik Flannigan, and Jonathan Pont