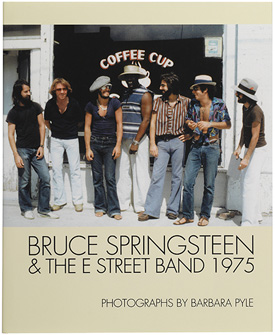

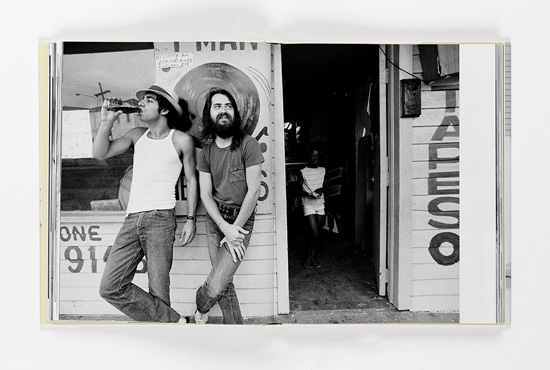

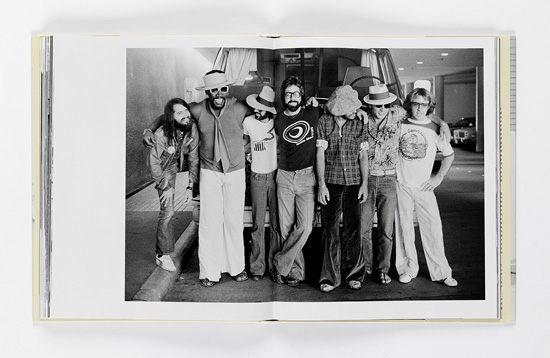

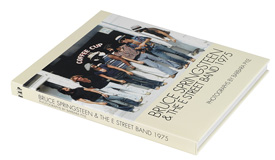

The cover of Barbara Pyle's recent book of photography, Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band 1975 (Reel Art Press), shows Springsteen and the band in September of that year, in front of the Coffee Cup Cafe in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. Pyle describes the locale as "Americana squared." And she ought to know: Pauls Valley is the "postcard-perfect town" where she grew up. In traveling with the band on tour that fall, Pyle was able to corral them into posing for this shot in her hometown, in front of the very coffee shop where she ate with her grandfather as a child.

The cover of Barbara Pyle's recent book of photography, Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band 1975 (Reel Art Press), shows Springsteen and the band in September of that year, in front of the Coffee Cup Cafe in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. Pyle describes the locale as "Americana squared." And she ought to know: Pauls Valley is the "postcard-perfect town" where she grew up. In traveling with the band on tour that fall, Pyle was able to corral them into posing for this shot in her hometown, in front of the very coffee shop where she ate with her grandfather as a child.

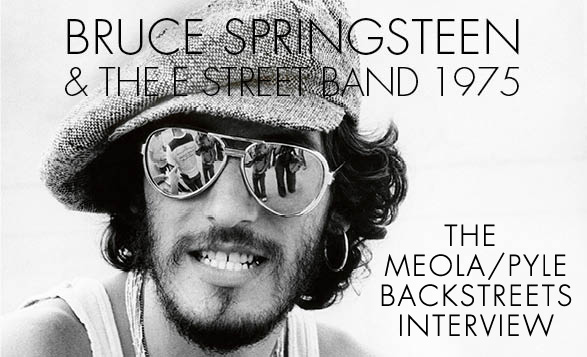

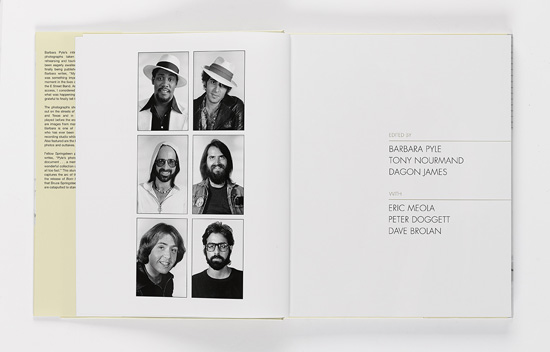

A captivating record of the Born to Run era, Barbara Pyle's images of Springsteen and the band in the mid-'70s are as indelible as her friend Eric Meola's cover shot for the classic 1975 album. So it made perfect sense to sit the two down together. Meola and Pyle met in 1974 as fellow photographers in New York City, but soon they were bonding over the music of Bruce Springsteen, taking in shows together on the Jersey side, and visiting the Record Plant where labor continued on Springsteen's third album.

Four decades later, to mark the arrival of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band 1975, we asked Eric to interview Barbara and reminisce. Out of their conversation comes a portrait of a woman "driven," as she puts it, to pull out of Pauls Valley and follow her dreams. While in college at Tulane she met Allen Toussaint and immersed herself in the New Orleans music scene. She worked as an undercover photographer for NBC News, a marine photographer shooting the America's Cup, and a documentary filmmaker at Turner Broadcasting. She was there for the founding of CNN and went on to co-create Captain Planet, a defining achievement in her ongoing environmentalism.

In the grand scheme of her fascinating life and career, Pyle's time shooting Springsteen and the E Street Band — what might be the pinnacle of another life — is just one of many stops along the way. But the work itself stands tall, and the impact Springsteen's music had on her in the mid-'70s is still apparent today. As she tells Meola: "I was born to run, and I'm still running."

With the anniversary of Born to Run upon us this week — as well as Springsteen's autobiography by the same name due next month, and the historical marker just erected at the site of 914 Sound Studios — we take you back to the Born to Run era with The Meola/Pyle Backstreets Interview.

Eric Meola: Let's start back in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. What was it like growing up there?

Barbara Pyle: If you've ever seen Happy Days, that was Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. Take Happy Days and put them in the country! It couldn't have been more fun. We were dragging Main, going to the drive-in, hanging out at the Dairy Queen, just like in the movies.

What was your hometown like?

Pauls Valley is a postcard-perfect town. It's been historically preserved with two original, wide brick main streets. We had one movie theater, the Royal, and Bob's Pig Shop, our local hangout. Both are still there. Have you ever seen The Last Picture Show?

Of course.

Well, that's Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. Population 6,000. High school class of 125. I missed my high school reunion, which is a darn shame because I love those people.

We had dance parties all the time. I was a very good dancer with a great dance partner, Mickey Warren — we won contests together. We were so lucky to have grown up with that rock 'n' roll music. We danced to all those songs when they first came out. Roy Orbison was and still is one of my favorites — when he sang "Only the Lonely," he was talking to all of us. We had hayrides, where we got in a big old wagon behind a tractor; I learned to drive on a tractor. We'd go down by the river for campfires and cookouts. It was idyllic.

What about your parents?

My parents were exceptional. They deserve the credit, my mom in particular, for giving me the ability to see a future for myself. They both had IQs off the charts. Dad was very funny, a brilliant man. My mother was a creative. We had a simple life.

What did he do?

My dad was a farmer/rancher. They scratched out a living. It was really hard. My grandfather had a little shop called The Produce House. He bought and sold chickens and eggs, broomcorn and pecans. They called it The Pecan Barn, too. It's a spectacular little building. Now I've moved to Saint Lucia in the southern Caribbean, and I'm here for good. But I've always dreamed of going back, setting up a funky little studio in The Pecan Barn, and just photographing the wonderful people and things in Pauls Valley — I wouldn't have wanted to be born in any other place or to have any other background.

And there was your sister, Kitty.

Unfortunately, she died of a very rare disease about ten years ago. Kitty was my sister, she was my best friend and business partner. At Turner Broadcasting, I hired Kitty to be my production road manager. We travelled together. Whenever we went on a film shoot, Kitty took care of all the logistics: travel, money, hotels, all that stuff. Kitty was the person that kept me together; she kept me together on every level. I miss her more than words can describe.

Growing up in Pauls Valley, did you have any sense of what you wanted to be or what you wanted to do at that point?

Oh, Eric, I'm one of those crazy people that was born with a mission! I told my mother early on that I wanted to document the diversity of humanity before everybody was in blue jeans. Not exactly in those words, at that age, but [laughs]... that was my mission statement, and that is exactly what I did.

I was always going to be a filmmaker — that was my vision, my goal — but I never dreamed that it would happen as fast as it did. Since I wanted to make films, I decided to start off as a still photographer. I got all kinds of little jobs, like shooting hotel brochures, which took me to remote locations. Peru, Ghana, Brazil, you name it. They would give me three weeks free in the hotel, I would shoot the job in a week, then spend two weeks photographing the place and especially the people.

So when did you start taking pictures?

At Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans, the women's school that was housed within Tulane, until Tulane closed it after Katrina. I couldn't remotely afford a real camera then. I had a little Brownie that my parents gave me, and I'd been snapping away in Europe, but my first published work was a portfolio of jazz funeral photographs by Michael P. Smith, which I edited and laid out for the Tulane yearbook.

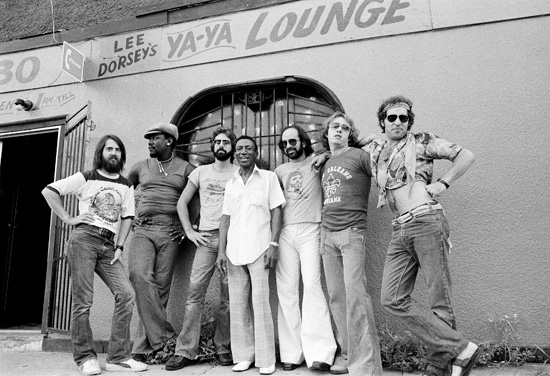

Luckily, my roommate was one of the first African-American women to be admitted to Tulane. And boy, what a break that was for me, because Allen Toussaint was her boyfriend. In the blink of an eye, there I was in Cosimo Matassa's recording studio with Allen, watching him work with Lee Dorsey. As a scholarship student, having a job in college was a part of the package. I was hired by the New Orleans Jazz Archive, because I had already established a solid base in New Orleans music. It was my job to take snapshots and interview veteran New Orleans jazz musicians from Preservation Hall, like Kid Thomas and Kid Sheik.

- Barbara Pyle returned to New Orleans in 1975, where she photographed the E Street Band with her friend Lee Dorsey

So this is all way before meeting Bruce? Photographing Bruce?

I was active in the New Orleans music scene years before meeting Bruce, in the studio for albums Allen Toussaint produced with Doctor John, Professor Longhair, Earl King, The Nevilles, James Booker, Ernie K. Doe… pretty much all the New Orleans jazz and R&B greats, even Chief Jolly and the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indians. I spent more time in a recording studio than out. I designed and shot some of those guys' album covers.

Amazing.

And guess who hauled Patti Labelle and Nona Hendrix around New Orleans's finest dives in her '69 white Cougar convertible after they recorded "Lady Marmalade"? Remember that one, Eric? "Voulez vous couchez avec moi, ce soir?"

I was a studio rat. I learned a lot about mixing and music — though certainly not Bruce's music, not yet. My background of Pauls Valley and New Orleans was a combination that could not be beat. Very solid country, jazz and R&B roots! My nickname in Oklahoma was "The Rhinestone Cowgirl," because I always wore rhinestones. I still do. "Rhyme-stone" is what they called me in New Orleans.

Despite how much New Orleans means to you, soon after that, you were moving to New York and opening the Women's Services clinic. How did that come about?

I went abroad in my junior year to Kings College, London — originally a math major going to Glasgow, but switched to Philosophy to get to London. Racking up forty-two hours of straight 'A' grades at Kings landed me in grad school for my senior year since I'd exceeded the undergrad program. After being chosen as the Outstanding Student in Philosophy for all of Tulane, I got a Woodrow Wilson fellowship. Then NYU offered me a full scholarship, and it was another dream come true. I loved New York City.

Graduating with highest honors had a hitch. As a senior, I now had to write a dissertation. Dr. Hale Harvey was also writing a dissertation. We had the same supervisor who couldn't read my paper because he was so stuck on Harvey's. I went to meet Harvey and asked, "Can you just cut me some kind of break here? I'm trying to graduate with honors so I can get a scholarship to grad school. You've been doing your PhD for years. Give me a week so I can get my thing done?" He agreed.

When we started talking, he actually hired me. I was going back to London that summer. He wanted research on existing sex education and healthcare modalities in Europe. Based on that research, we created the Community Sex Information and Education Service together. When I went to NYU as a grad student, he asked me to continue the research. With sex education comes the study of STDs and abortion, so these subjects were added to the scope of the work.

In researching who was doing what and where with abortion, I met Howard Moody, who had founded the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS). It was a network of clergymen, priests and rabbis all over the U.S.A. that referred women out of the country for abortions. At the time, the CCS was referring patients to Japan and Puerto Rico. It was either very expensive or dangerous.

Harvey had set up a clinic in New Orleans. He actually had me buy the first suction apparatus machine ever imported to the United States. I bought it on Bond Street in London — it was sitting right in the window — and brought it back on the plane. An introduction to Howard, and the CCS started to send clients to New Orleans.

Then, abracadabra, the law was changed in New York and abortion became legal overnight. It was obvious I should talk Harvey into coming to New York — because legal abortion is a much smarter place to be than illegal abortion. Together we created a clinic called Women's Services.

Just after starting grad school at NYU, the clinic opened. If you don't know anything about anything, you can do anything — that's my motto in life. Have no fear; follow your dream with a red hot passion. That's a bit of advice. I rented a furnished medical facility on East 73rd, and Dr. Harvey arrived with a truck full of equipment. I operated the clinic for three years.

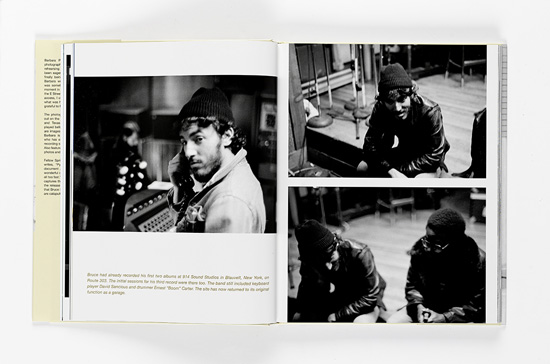

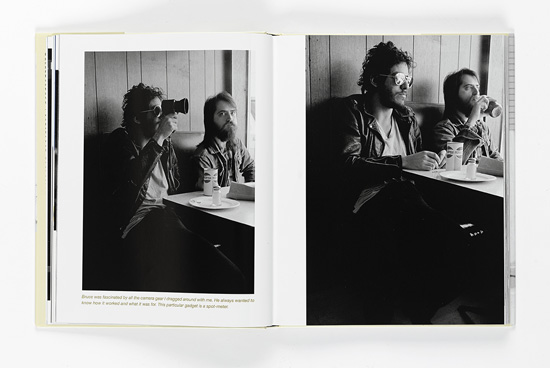

- One of Barbara Pyle's first offstage photographs of Bruce Springsteen, in 1974 at 914 Sound Studios in Blauvelt, NY.

Tell me about starting to photograph Bruce, how did that happen?

I was a minor celebrity, because for a young person to have created something like the clinic was unique. TV and radio channels frequently asked me to debate the abortion issue, and since my fields of study were philosophy, logic and ethics, that came easily. Exponential population growth and its impact on the environment was another area of expertise that helped me out-perform the opposition in the debates.

By this time, I had my first camera and was running around taking pictures. Breaking into photography happened very quickly. My first job as a photographer came from Earl Ubell at NBC News, who had interviewed me a number of times at the clinic. When I left, I breezed into his office and asked for a job. And he gave me one, starting off with really simple assignments, like perp walks, when a suspect makes the long walk from jail to cop car. All these huge cameramen with their film cameras were like a wall of flesh, shoving each other aside to get the shot. I'd be there with my Leica, so at least NBC News could be guaranteed a headshot. I became kind of a jinx to all these cameramen, because if I was there on the perp walk something would go wrong for them — but I would always get the shot.

So I was promoted to doing my own stories at NBC News. Anything that was too dangerous or conspicuous for a film crew. If I was shooting homeless people, I had to be in disguise as a homeless person. I was an undercover photographer for NBC News for quite some time. Then I started getting other clients: Playboy Magazine, shooting nudes for our friend Sean Callahan, and Schaefer Beer.

So that must bring us to the Schaefer Music Festival. [In the summer of '74, The Schaefer Music Festival in Central Park hosted numerous musical acts over 24 nights in New York, from July to September; Springsteen and the E Street Band famously opened for Anne Murray on August 3.]

Yes. I was doing tabletops for Schaefer Beer. There's nothing more boring than that. As sort of a perk, they gave me the Schaefer Music Festival in the summer of 1974. I covered all of it, shooting every concert. Then there was one performance that just dropped me. When I heard Springsteen's music, it just blew me away.

So that was the moment for you.

When I listened to the first two albums in your studio, that sealed the deal. I really heard the lyrics and the hook was deeply imbedded in my mouth. The very first concert we went to, we went backstage and there was Roy Bittan. I had known Roy for years. His best friend, Bud Brimberg, and me were in college together. Bud introduced me to his great friend Roy, and now Roy is my great friend too.

And soon enough you were a studio rat again, with Bruce and the band. They were still recording at 914, is that correct? [914 Sound Studios, in Blauvelt, NY, is where Springsteen and the E Street Band recorded their first two albums, along with Born to Run's title track in 1974, before moving to the Record Plant in NYC.]

Yes, initially, they were recording at 914.

How did you end up there?

Clarence invited me. But I only took a couple of frames, of Bruce with David Sancious and of Bruce walking out the door. Then we went to a little greasy spoon restaurant; I remember riding with Clarence in his little Volkswagen. I took one my favorite pictures of Clarence there. He was eating chicken and looking straight to camera with his twinkling, soulful eyes.

And then after they moved to the Record Plant, you were around a lot more.

Yes, I was.

So tell me about the last day of Born to Run being recorded. The shots that Bruce said should have been the cover.

I was at the Record Plant every night. It was bizarre, and I don't have any idea why Bruce wanted me there. It was going on and on, and we were all caught in the twilight zone. It was nerve-racking for everybody, even for me with nothing at stake. They had everything to lose, and with rumors that CBS was about to drop them, they were fighting for their lives.

At the very end, during that whole infamous marathon three-or-four-day recording session, everybody was a zombie. Bruce was recording Clarence's "Jungleland" solo for about… I don't know how many hours. If I say 12 hours, it might have been 24, it might have been 36, I have no idea — it was endless. And with each take, Bruce would hum it, Clarence would play it. Clarence would say, "That's it, Boss," and Bruce would say, "One more time, Big Man."

They finally quit because they had to go into rehearsal at five in the morning. I went with them with my Leica in my purse.

The rehearsal hall was a real dump. I'm sitting on a little staircase right in front of them, trying to disappear into the woodwork. But it wasn't a matter of breaking code and interfering with Bruce's headspace. The album was done, they were rehearsing, and they were leaving in just a few hours for the Born to Run tour.

- "Dawn Rehearsal," July 20, 1975.

So those last pictures were taken on the same day that they were headed up to Providence to start the tour.

Yes, on that very day at 6:30 in the morning, right when the sun came blazing through the ragged curtains, creating that very dramatic light.

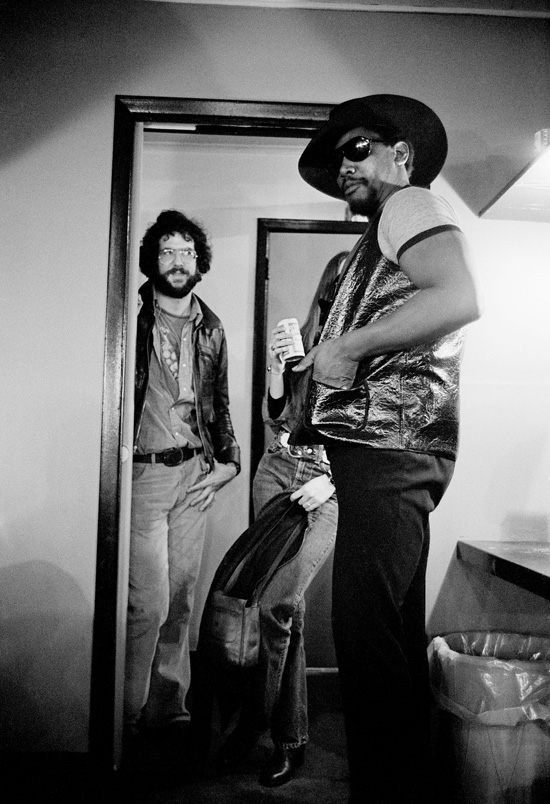

- Eric Meola and Clarence Clemons backstage at NYC's The Bottom Line, August 1975.

After Born to Run came out, you were with Bruce and the band in New Orleans and, of all places, Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. Tell me about September.

They played the Bottom Line in August and were all still pretty tense, even though they took NYC by storm. If I met them in New Orleans and showed them around, the very least it would do was put a smile back on their faces. So I did — I showed them my New Orleans, the New Orleans that I love, that's been my heart, soul and inspiration for most of my life.

And from there, were you on the tour bus?

They had such a good time in New Orleans, they said, "Meet us in Houston." I said, "Why not!" Then we did the same thing, running around, having a blast doing all these off-the-wall things in Houston: pawn shops, weird festivals, all kinds of stuff. Most bands, when they go on the road, they do their show, eat late, go to bed late, sleep until soundcheck, then go to the venue. By coaxing the band out of the hotel rooms, we had a fantastic time in Houston.

This time they said, "Just get on the bus!" And again, I said, "Why not! You're going to Dallas, and Oklahoma… that's my home territory."

How did that iconic Coffee Cup Cafe photograph happen?

I got my parents to cook up a barbecue, because after we left Dallas in the morning, we'd be hitting Pauls Valley, Oklahoma at about hungry time. So I asked, "You guys want some legitimate, real deal, home-cooked barbecue?" What is anyone going to say to that? And our family home was only five minutes off the highway.

We hung out with my parents for a while. Everything was lovely. My parents loved them. They loved my parents. They loved my dog. Then it was time for us to go to soundcheck in Oklahoma City.

The Coffee Cup Cafe shot was not an accident. I planned it. Growing up, I used to eat there with my grandfather. It was one block from the Pecan Barn. It was iconic. Americana squared.

So Pauls Valley was a bit of a trick. You know what it's like, Eric. You find a great background, put someone in front of it, and boom, you've got a great picture. So I wanted to put the band in front of that background. And that's where the Coffee Cup Cafe shot came from. I planned it, we did it, and it's a cool picture. Any photographer would have done the same thing.

That was the only time I got them out of the bus to take a picture. All the other photographs were in the natural scheme of things. The only shot Bruce ever asked me to take was a portrait of the band later that night in Oklahoma City. It was almost Bruce's birthday, and Born to Run had just hit the charts. A birthday cake shows up with the news about the record, which is why he's grinning like a Cheshire cat in those photos.

There are so many different versions of how Bruce came to be on the covers of both Time and Newsweek. I actually invited [Time photo editor], John Durniak to come down to the studio in '74 and I played him The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. I was like this gushing kid, jumping up and down saying, "You gotta put this guy on the cover!"

I played a small part in those covers myself, after shooting in Red Bank [Springsteen and the E Street Band played the Monmouth Arts Center on October 11, 1975].The gig was swarming with Newsweek people, and you know you can't do both. If you work for Playboy, you can't work for Penthouse; if you work for Time, you can't work for Newsweek. You pick your client and you stick with them. Even if you're not employed, if you're a stringer for one, don't string for the other.

So that Saturday night, Newsweek was all over me about my file cabinets of negatives. Nodding and smiling, I said, "Oh sure, no problem. I'll bring them to you on Monday."

I went to your studio and got all your stuff, then got all Richard Barnes' stuff, and I went to John at Time and said, "This is what's happening, John. Newsweek is doing a cover."

I know what you're saying, and I agree to some extent, but I think ultimately it had to do with one thing. Ultimately it had to do, as Jon Landau would say, with Bruce. It was a series of events.

Yeah, it was a series of events. But that Monday, it was now or never. Newsweek was doing the cover. Period. And Time was just hoping and praying that some disaster would happen, because the last thing they wanted was a double cover. John Durniak didn't want to do it, and [Time director of photography Arnold] Drapkin didn't want to do it. But it was either do it or get scooped by Newsweek.

All I did was walk in there and say, "Okay, here is all the stuff Newsweek wants, but I'm not going to give it to them. Here it is — it's up to you guys now."

I have to say, I kind of regret it, because perhaps Bruce wasn't ready for that level of fame. He wasn't happy about the two covers. He had a different plan for growing his fan base.

It's one of those things that entered the whole mythology of all things Bruce. Let's talk about Ted Turner and yacht racing and all that stuff.

I left the States in 1979 to move to Jost van Dyke in the British Virgin Islands. I'd had it with New York. I found myself in the islands with no money, but with a camera.

So I took up marine photography, which is a very competitive field, but photographing boats was second nature for me. Shooting nudes for Playboy Magazine taught me every woman has at least one beautiful angle, just like every boat, so instinctively I photographed boats as if they were women. Shooting portraits of 200-foot luxury yachts was a very lucrative career, as was advertising photography for Rolex and international yacht charter companies.

I started photographing boat races, and I was successful at it, going all up and down the islands. In 1980, I heard about a big boat race in Newport, the pinnacle of yacht racing. I had never heard of the America's Cup, but I covered it for Time Magazine that year and in 1983. By this time, I was a published and accomplished marine photographer. I now had Rolex, as a client and I'd worked for Time Magazine for years.

My first day in Newport, Rhode Island, I met Ted Turner. To make a long story short, within 48 hours, he started offering me jobs; he must have offered a dozen. I said, "Ted, I'm being paid a fortune to go sailing. Do you really think I to want quit my lucrative photography career and live in Atlanta, Georgia? In your dreams!"

Then a report came out called "The Global 2000 Report to the President." This report took all the current trends of environmental degradation and projected them into the next 20 years. It was a horror. Ted said, "This is your job description. Get this information out to the widest possible audience. I'll give you editorial freedom." That was the Ted hook in my mouth, so I moved to Atlanta to be a founding member of CNN with those global issues as my mandate.

So your title was…?

I was the documentary division for critical global issues, but there was no title, no staff, no budget. I had to figure out how to use smoke and mirrors to get things done. Ultimately, I became Corporate Vice President of Environmental Policy, which was the first corporate job title in the world with environmental in it, but that took about nine years.

At least it didn't take long to find sponsors. The first funding came from UNFPA [United Nations Population Fund]. They wanted me to film a population conference in Beijing. The ticket cost five grand. For that same five grand you could buy a round-the-world ticket. So I went to ten countries and filmed various solutions to the population issue, because even now we're dealing with massive, exponential population growth.

This was with a crew from CNN?

Ha! I traveled alone with an old, broken down CP-16 [16mm motion picture camera] that I found jammed in the closet at Turner. No crew, no budget. UNFPA bought the plane ticket, provided a car, a driver and a place to stay wherever I went.

Astonishingly, I came back with moving pictures! Most looked more like moving stills, because I didn't know about panning and tilting. It was hard to edit, but we did cut it into an award-winning film. I'm a self-taught filmmaker, not the best in the world, but prolific, with 65 documentaries winning hundreds of industry awards.

I financed the films outside Turner Broadcasting, but Ted gave me a roof. Being in the company and having an office came with begging rights for air time. I could guarantee my films were going to air. Other filmmakers had no guarantee of distribution or outlet. I had guaranteed distribution, so I was much more fundable.

Tell me about Captain Planet.

My job description was to disseminate the information about the dire future of our planet in the Global 2000 report. To date it's still the most comprehensive study of our planet's future. The closing sentence of the summary makes your hair stand on end — it went something like: "Based upon the available evidence... we have no doubt that the world, including this nation, faces enormous, urgent, complex, irreversible problems in the decades ahead, unless immediate action is taken."

Guess how much action was taken? None. This was a Carter-commissioned report at the end of his presidency, so Reagan did nothing. He buried the report. I spent nine years making documentary films and distributing them to the worldwide network of television stations that belonged to CNN's World Report, which I co-founded. They would rebroadcast the programs in their own languages. I was transferring technology, finding replicable solutions to real problems, looking at eradicating poverty, creating jobs for women, literacy, health, environmental issues, sustainable jobs, capacity building, all that stuff.

How did that lead to a children's show?

The documentaries were working to a point, but we were reaching the converted. People who watch documentaries already care about the subject, otherwise they wouldn't be watching. Ted and I agreed on a new strategy — simply, get them young, train them right. Over a period of time, we started talking about a children's show. Then in 1989 he said, "Captain Planet." I said, "What else?" He said, "That's your problem, kid!"

So here I was again doing something I didn't have a clue how to do — which is, in my opinion, the best way to take on something huge. The less you know about what can't be done, the more likely you are to be able to do it. And what we did was Captain Planet.

Captain Planet and the Planeteers was designed specifically for people who were born in 1985. We began broadcasting in September 1990, more than 25 years ago.

It's a cartoon show about five children from five regions of the planet, each endowed with a magic ring to control an element of nature: Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water, and the missing element is heart. Heart is actually the most important element, because without heart and compassion, we are not going to save the planet. Typically, some eco-emergency happens and Mother Earth calls them together and says. "Okay your next assignment is…" Kind of James Bond-ish. And they fly off in the eco-copter.

Most of the eco-adventures and environmental emergencies were based on our documentaries. Although we tweaked and exaggerated them to what we thought was impossible. The most sickening thing is that we made episodes about absurd things we thought could never happen, and in the past 25 years it has pretty much all happened.

So let me ask you this question. Three words: optimist, pessimist, and realist — where are you right now?

I'm a realist. We are in trouble.

I read this recent op-ed piece in the New York Times that said (and I'm paraphrasing), "It is time we recognized all the world's forums on climate change are having few results. And we have to accept that the economic reality for most nations is that we just won't accept the environmental quotas needed to modestly reverse carbon dioxide emissions."

That's actually true.

Right. But the article went on to say, "Therefore we should accept what will likely be a scenario in which we do battle with nature and should concentrate on infrastructure defenses." Spending money… in other words, let's go to defense instead of offense.

I agree completely. We should be doing both. If I were king of the world, I'd say, let's do a double track. Let's keep working towards all the things that must be done — creating jobs for women, literacy for everyone, literacy is key to saving the world — but let's cover our backs. Instead of spending money on projects like dams, why don't we start thinking about large-scale infrastructure to protect the edges of our planet? The edges of our planet are in danger. The Maldives are going underwater. We are going to lose Bangladesh — why doesn't anybody care about that? Instead of building a dam in Brazil, shouldn't we be building defenses, like in Holland, around Bangladesh? Around New Orleans? Around Manhattan? Around the Florida Keys?

Why do we need more power? Why do we need more, more, more? When are we going to learn that enough is enough? Why are we doing the crazy shit that we're doing on this planet? I love what Ghandi said and I have lived by it: "There is enough for every man's need, but not for every man's greed."

I think as a species, we failed. Climate change is inevitable at this point. We really need to start making emergency provisions. It's going to happen in a domino effect. It's not just going to creep up on us; we are going to hit a tipping point. One of these glaciers is going to calve, or something else unthinkable will happen, and the consequences will be unimaginable.

But at the same time, despite the fact that you are a realist, you are still going on with Captain Planet.

Captain Planet is our best shot. We had a fantasy that we could create an eco-literate generation of youth. Well, we did it. There are 600,000 active Captain Planet fans on Facebook from every corner of the world — they even call themselves Planeteers.

We have the power within us to make the world a better place. We endowed a generation of young people with the knowledge that they have that power. If they were an older child watching Captain Planet in 1990, they are now 35 or 40. Planeteers are elected officials. Planeteers are doctors, lawyers. Planeteers are sons and daughters of the heads of multinational corporations around the world. We are everywhere.

If, in fact, the world gives us another ten years, these young people are going to be running the show, and it's going to be a different show. They believe in sustainability, they believe in equity, in justice, in nature, in not destroying nature, they believe in all the values of Captain Planet. So I believe in the Planeteers.

There is a Springsteen song called "Growin' Up," and to some degree, Bruce has grown up. He went and did something we never thought he would: he got married and had kids. He has become not only successful but much more introspective, I think. He has donated money to charities. You've grown up, you've gone on to become an environmentalist. You've won the [United Nations] Sasakawa Award, and on and on. As we get older, I think we start to really measure ourselves a lot by what we haven't done. Do you have any sense of accomplishment, or more importantly, some inner peace, some satisfaction?

Absolutely. If I die tomorrow, I have delivered a television program with my colleagues that already changed the world and will continue to change the world for the better, forever. That gives me a massive sense of accomplishment. I am so proud of these Planeteers. I count them among my best friends. I respect them, admire them, they are my equals, they are going to make the difference. They are the tipping point for good.

These young people have the vision, the ability, skills, talent, and knowledge to change course on this planet. What we might not have is time.

What's next for you?

At the same time as the book was launched, I opened a gallery at 59 Carmine Street called, appropriately enough, Carmine Galleries. It's chock-a-block with photos of Bruce and the band right now, but for our 'Hump Day' party between the two Jersey concerts [on Wednesday, August 24], we're hanging one wall with some of my historic photographs from New Orleans, the America's Cup, even some old nudes from Playboy Magazine.

Over the past two years, I've been moving my life to Saint Lucia, the crown jewel of the Caribbean. Sailing is my passion, and last year, the Barbara Pyle Foundation started a competition called the Saint Lucia Hobie Cat Challenge, pitting the tourism industry's unsung water sports heroes against each other to win sponsorship towards professional sailing credentials. BPF also sponsors a young winning J24 crew, who have their sights on the J24 Worlds next year. I travel back to the U.S. to compete in summer regattas and last year won the Vineyard Cup and the Hereschoff Regatta. I've returned to my life as a marine photographer — the difference now is I photograph the boat races while winning them!

Of course, Saint Lucia has its very own Captain Planet — Wynel Desir — and Planeteers are joining the movement through school projects and an essay competition. Plans are in the pipeline to start after-school environmental and gardening clubs for students.

I'm fixing my house. I'm getting a boat. I'm exploring opportunities that will create jobs for the wonderful people of Saint Lucia. They are why I'm here. I love how they're always laughing. I'm happy here.

I want to end on one thing, which is to come back to the E Street Band in 1975 for a moment. I know that in the big picture we've gotten older, and we have different agendas from when we were younger . . .

No, Eric, that's where you and I are very different. I was born with an agenda! I've always had the same agenda.

Well, there are very few people who have that. I think your book is terrific, and it not only brings back a lot of memories, it really immerses me back in that time. And of course it was a very romantic time, when we didn't know what was going to happen with Bruce. Now that we do, it's very hard to reconcile the Bruce Springsteen of 1975 with the Bruce Springsteen of now. We can see how it happened, I suppose.…

Let me explain something to you. If you listen to Bruce's lyrics on his first three albums, they were my anthems. "We gotta make it real. We gotta get outta here to win." I related very strongly to Bruce's lyrics, because that is what I was doing. I had to "get outta" Oklahoma to follow my dreams. I was born to run, and I'm still running. Bruce put words to my internal feelings that I never would have been able to express myself. That is why I adored that album so much — because I was driven. I have always been driven.

I said to Dave Marsh once, there are times when I'd swear that I wrote these lyrics. And what I meant by that was, of course I didn't have the talent to write those lyrics, but Bruce's talent was that he made me feel that what was inside of me, in my mind, was what he was saying. And I think that is what you are expressing.

Exactly. There is something for everyone in Bruce's lyrics. That's what explains his universality and immense popularity. His music is the greatest. The lyrics are the most powerful, in my opinion, ever written. He was talking to you, and he was talking to me, and he was talking to everyone. Because everyone, deep down, believes that there is something better. That we have got to strive for that something better, that we have to get out of here to win, that…

We've got one last chance to make it real.

We've got one last chance to make it real.

Edited by Dee Lundy-Charles (Saint Lucia) and Christopher Phillips, with thanks to Eric Meola and Barbara Pyle as well as Tony Nourmand and Rory Bruton at Reel Art Press.

If you're in town this week for Springsteen and the E Street Band's New Jersey shows at MetLife Stadium, come meet Barbara Pyle on the day in between the two concerts, at Carmine Galleries in NYC. Barbara will be there for a special "Hump Day" print and book signing on Wednesday, August 24, from 7-9pm. Carmine Galleries is at 59 Carmine Street in the West Village.

If you're in town this week for Springsteen and the E Street Band's New Jersey shows at MetLife Stadium, come meet Barbara Pyle on the day in between the two concerts, at Carmine Galleries in NYC. Barbara will be there for a special "Hump Day" print and book signing on Wednesday, August 24, from 7-9pm. Carmine Galleries is at 59 Carmine Street in the West Village.

If you can't meet her in person, Barbara has signed custom bookplates especially for our readers, affixed to the title page of each copy we send out. Order this signed edition of the Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band 1975 hardcover, in stock now, from Backstreet Records.