Less than 48 hours after the announcement of a 2012 tour, Backstreets had the opportunity to speak with E Street Band guitarist Nils Lofgren, who seems just as excited by the news as the rest of us:

Up until a couple of days ago I could honestly say there were no plans that I knew of. Rumors are just that — I learned that as a kid working with Neil Young. Everyone talks about ideas, but they are just ideas until they are made a reality; until then you have to ignore them and get on with your own life. At the end of every tour, inlcuding two years ago, you think is this the last show I'm ever going to play with this great band.... At least I know by summer I'll be playing with some dear friends and as great a band as has ever been. That is a blessing. The fact that I've got a good record out now, thank God I did it when I did.

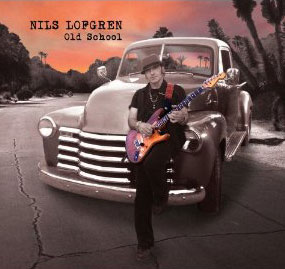

Lou Masur, author of Runaway Dream, spoke with Nils for Backstreets about that new record, Old School, and much more — including his double hip replacement, the loss of his dear friend Clarence, his work on the new Patti Scialfa project, and tap dancing. Photographs by John Cavanaugh.

Backstreets: Old School is the first album of new material since 2006. Was most of it written after the Working on a Dream tour that ended two years ago?

Nils Lofgren: Pretty much all of it was with the exception of "Irish Angel," a beautiful ballad I've been singing in my show by Bruce McCabe for years and I've been meaning to record and just never got it together til now. And then there was this wild old singer Root Boy Slim from Washington DC. We were old friends. Of course, Root Boy passed away a long time ago. He wrote very witty but controversial songs that either made you laugh or cringe. We were one day, decades ago, in my back yard in Bethesda, Maryland, and we wrote this beautiful haunting ballad together, "Let Her Get Away," and one of my goals was to share that on this record.

Nils Lofgren: Pretty much all of it was with the exception of "Irish Angel," a beautiful ballad I've been singing in my show by Bruce McCabe for years and I've been meaning to record and just never got it together til now. And then there was this wild old singer Root Boy Slim from Washington DC. We were old friends. Of course, Root Boy passed away a long time ago. He wrote very witty but controversial songs that either made you laugh or cringe. We were one day, decades ago, in my back yard in Bethesda, Maryland, and we wrote this beautiful haunting ballad together, "Let Her Get Away," and one of my goals was to share that on this record.

Other than that everything was new, and I got off the road and I was pretty sharp musically and excited to get back to my next batch of music. I took my time for a year and a half, wrote and recorded, and went on the road and sang to keep sharp and just to work. And I found time to be at home with my lovely Jersey wife from West Orange and our six dogs and tried to find a balance between touring and playing. Sometimes you make a record and all of a sudden you're just in this cave for months on end. For me, I lose my musical sharpness if I don't sing for people. So I found a nice balance between all of it and I think it reflects in this record.

You decided to produce the album, with the exception of one song. What went into that decision?

I just wanted it to be a homegrown thing. I haven't had a record deal in 16 years. I'm not looking for a record deal. I've got a website that I really feel good about [www.nilslofgren.com]. A lot of free music. Guitar School is there. Videos. And stories about past tours on the Rockality page. The stuff that I am proud of, and for me it's comfortable to have the freedom to do whatever I want musically and be creative. It's served me well. It'ss grass roots and kind of off the grid, but that's fine. I wanted to do [the album] at home so I could be around and be available for my family and help my wife out, because I'm always leaving to play and tour and sing. So I just wanted to keep it real homegrown so I could write the songs — and even after I wrote them, I didn't record them until I could play them and sing them live.

A lot of this album is also recorded live. Talk about old school!

Generally, I put a drum track down and then I actually set up a mic and was ready to sing and play live, and I wouldn't even bother until I could do that. In the past, I'd have a great song but I wouldn't have words for the bridge... and you cut the track, and all these different elements are being written and created as you go. There's nothing wrong with that. But for me, for this record, the whole "old school" concept... I felt like if I can get a live performance with live guitars [as] the core, then when you start coloring in around it you have a feel that never goes away.

But I have to say, there's a caveat there. I don't have patience in the studio. I have none. It's very challenging for me to find the patience, and I have to kind of trick myself and give myself limitations like that. So okay, I've got a live vocal. Well, that is more fun to color in around and the live vocal never gets homogenized. It was live. It retains that feel. There are people like Peter Gabriel who are masters at crafting very powerful emotional records. There is no wrong or right. But for me it would have been wrong to just craft the whole thing as a jigsaw puzzle. I felt like if I got the nucleus of the song and the lyric live, then the rest would come.

Even when I play guitar I kind of trick myself. One day I'd be the amateur engineer and the roadie, and after four hours I'm ready there with the guitar and I'm tired, I don't even want to focus that hard, so I might just play without recording just to get a feel for the guitar and the sound. And when I really felt like I had the right guitar sound, I'd set it down and I'd walk away that day.

Then the next day I'd come in and: today I'm just a guitar player. I didn't need to be the producer. I'd just jam and play hard. Do a whole take or two or three or four. But not nit-pick, not craft line by line. Just play. And then maybe the next day I'd come back and I'd just be the producer. And it helped me not get overwhelmed. It's like, today all I'm doing is listening to four emotional guitar tracks. And I'd go, yeah, this one's great for 40 seconds, and maybe I'll switch over to this one which had a little better feel for the last half of the song. So I came up with this theme of keeping it fun but emotional, and still accomplishing making a record that I was proud of. I took my time, over a year and a half of literally starting to write and continuing to tour and being available for my family. It is probably the most balanced journey I have ever had putting a record together.

Then the next day I'd come in and: today I'm just a guitar player. I didn't need to be the producer. I'd just jam and play hard. Do a whole take or two or three or four. But not nit-pick, not craft line by line. Just play. And then maybe the next day I'd come back and I'd just be the producer. And it helped me not get overwhelmed. It's like, today all I'm doing is listening to four emotional guitar tracks. And I'd go, yeah, this one's great for 40 seconds, and maybe I'll switch over to this one which had a little better feel for the last half of the song. So I came up with this theme of keeping it fun but emotional, and still accomplishing making a record that I was proud of. I took my time, over a year and a half of literally starting to write and continuing to tour and being available for my family. It is probably the most balanced journey I have ever had putting a record together.

Of course the last few months, inevitably there had to be those twelve-hour days plus, when all you are thinking about is the record and running orders. I moved into a Pro Tools studio to mix it with a great local engineer to really give me freedom with what I recorded, because I'm not an engineer. But I get things to tape well and safely, and then I had a real engineer help me.

The album sounds great, and we keep listening over and over again to the songs. The guitar solo on "Why Me," the last song on the album, is especially soulful, piercing and memorable.

It's funny, because "Why Me" is the first song I recorded. I had ten songs written and another eight or nine that were in the works, and I realized I better start recording, though part of me was loathe to do it because it was so much work. So again, a little psychological game I play with myself. Brian Christian, who is a dear old friend, was the engineer for Aerial Ballet and many great projects including Alice Cooper's hits; he worked on The Wall, Peter Gabriel's records. He got out of the music business 20 years ago, but we stayed in touch. One day he said, "Why don't you let me help you out and let's record something?" And I thought why not take this on, "Why Me" that I love. I got a live performance of the vocal, and Brian helped me put to together from scratch. That was the official start of the recording process.

In that song the narrator asks the question, "Is there hope in my catastrophe?" And while it is a mistake to confuse the characters in songs with the songwriter, there seems to be a lot in this album that is autobiographical. For example, the lyrics "metal hips and hard street ball" in "Ain't Too Many of Us Left."

It's a very personal record. It's really a reflection of having had a great 43 years on the road. I'm like anybody else: you live long enough, you start burying friends and family. That's part of life. I'm 24 years clean and sober. I realized either you're just going to have to go out in a blaze of glory or find a way to live without it, which I had no clue how to do. After having a ball — mostly playing basketball and doing backflips off of trampolines and getting up off drum risers of many a great drummer — to my horror, there was zero cartilage in either hip. I just completely destroyed them. And even the doctors wondered, how do you have 90-year-old hips? You're only 57! How did that happen?

I was in denial for a long time. I walked around in terrible pain for years. I finally begrudgingly did the research and had a great surgeon at the Hospital for Special Surgery, had both done at the same time, and my wife Amy moved into the hospital. It was a big deal for me. I don't like hospitals. It was scary. And I was coming up on my sixtieth birthday. And when you're a kid, you look at people that old and they are in the recliner watching their favorite football game and the kids are bringing their slippers and their drinks — and you realize that none of that is true in this day and age. You feel like a Rodney Dangerfield character. Nobody pays attention to you. Certainly nobody gives you the respect you thought you had coming. And yet, you have to have a sense of humor about it, because the world is a very different place.

In addition to no longer being this mythical revered character that you thought 60-year-old men were as a teenager, you also look around at the planet we are on and realize we are in deep trouble. There's a lot of bad stuff going on. You have to start focusing on the life around you, and all of those elements were something I wanted to write about. The fears and anxieties I have as a 60-year-old person on this planet I took great liberties with. The character in the song "60 is the New 18" is struggling with a lot deeper problems than I have. My wife calls our problems champagne problems. For the most part they are. But 13 years ago I had to go off and bury my dad, he was my hero. That's not a champagne problem. I just wanted this record to be authentic. The beauty of being a writer is you can take liberties and have the characters experience greater joy or greater tragedy as they navigate autobiographical feelings.

The song "Miss You Ray" on the album is not only about Ray Charles but all the artists and friends we've lost. In concert you've been singing it as "Miss You C," and Old School is dedicated to Clarence Clemons who you not only stood next to on stage for 27 years but you were close friends with. When you joined the band in 1984, what kind of welcome did he give you?

Everyone was sympathetic. Also it was a big deal that it happened five weeks before opening night, which is not the ideal time you want to prep for a band with hundreds of songs.

And a bandleader who likes to call audibles.

Yeah, Bruce will never follow a setlist, because he gets better ideas as a work in progress, and that's one of the beauties of the great band that it is with Bruce out front. Nevertheless, I think just naturally Clarence wound up being someone I spoke with off the road most frequently. We talked every week or more. I played gigs with his band once in a while. We had a very deep friendship off stage as well as on. So it made it that much more brutal when we got the bad news.

I was on tour in England and had high hopes after my last show, because Clarence survived the initial surgery, that I would fly to Florida and visit him at the start of a long but hopefully positive recovery. Out of the blue, two hours after I got off stage, to my horror, I got the call that he had passed away. Instead, I flew right to Phoenix, grabbed my wife Amy, went back to the airport and flew to Florida. June 21, on my sixtieth birthday, I had to bury my friend Clarence. I tried to ignore the day and the fact that it was my birthday. To her credit, Amy insisted on a dinner with a handful of the band and very close friends. And it turned out to be a kind of healing evening. I was prepared to just be miserable at a hotel and get ready to go back home. But that was kind of a blessing and kind of what I talk about in the song "Miss You Ray." Life is still grand, but you really have to pay a bit more attention as you take these losses — which everyone does.

There is also the sense of honoring the memory of the departed. I imagine that the announcement that Bruce just made that the band will be going back out on tour in part comes out of a decision that, difficult as it is, we must go on.

Up until a couple of days ago I could honestly say there were no plans that I knew of. Rumors are just that — I learned that as a kid working with Neil Young. Everyone talks about ideas, but they are just ideas until they are made a reality; until then you have to ignore them and get on with your own life. At the end of every tour, inlcuding two years ago, you think is this the last show I'm ever going to play with this great band. And meanwhile, what's the next great live thing I'm going to put together, how am I going to do it? I've had the blessing of that focus. It's all the same thing, making music. But after every chapter Bruce made the decision what to do next, including a great album and a tour that didn't involve the E Street Band. At least I know by summer I'll be playing with some dear friends and as great a band as has ever been. That is a blessing. The fact that I've got a good record out now, thank God I did it when I did.

Do you think between now and next summer you'll do a bit of touring behind Old School?

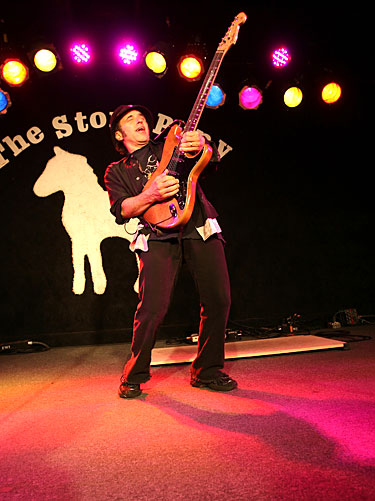

I do. I just did three weeks back east. I've got a couple of shows booked in February that I'm pretty sure I'll be able to honor. Right now there is no schedule. I've got an acoustic duo show with Greg Varlotta [left] that's really, really good.

I do. I just did three weeks back east. I've got a couple of shows booked in February that I'm pretty sure I'll be able to honor. Right now there is no schedule. I've got an acoustic duo show with Greg Varlotta [left] that's really, really good.

We understand it includes some tap dancing.

About a year after my surgery I flew that idea by my surgeon, and he said my hips were strong enough, and that, as long as I'm not jumping off tables, tap dancing is actually good because it challenges everything and surprises everything from the waist down. He thought that would not have been appropriate until about ten months into my recovery. I'm trying to be careful, because I don't want to go through that again if I live long enough. Tap dancing is considered low impact as long as you are not jumping off pianos. I'm just trying to be smart about it. The whole Working on a Dream tour, the last two years I've done quite a number of gigs, and I'm still just jumping around stage, flailing around, and saying "Oh my God, I'm not in pain." It had become part of my landscape for the last 15 years. Slowly but surely it went from just an annoyance to significant pain 24/7, and it's gone.

That's wonderful news. On Old School you also feature the vocals of a few guests: Lou Gramm of Foreigner, Paul Rodgers of Free and Bad Company, and Sam Moore, who needs no introduction. How did you come to work with them?

At the end of the record, when I realized I had 14 or 15 things in the works and I started to hone down to the top 12 or 11, whatever I decided the record should be, I started evaluating, since I have live vocals, whether I have any friends who might harmonize. It wouldn't be a forced thing but natural and kind of a musical earthy transition into something soulful as a harmony. I came up with those three, called them directly, and asked if they would listen to a track with the idea of considering singing harmonies for me. All three of them stepped up, loved what they heard, and made a commitment to help me. In fact Sam Moore, who lives in town [Phoenix] and did the Hall of Fame show with us recently, we met at a vocal studio we are both familiar with and my engineer came over and next thing I know I'm standing in a studio with Sam singing live with him on one of my songs. It was pretty intimidating. And a beautiful experience. Sam is a very kind, soulful man who made me feel very comfortable. I had ideas. He had ideas. He'd go places I never thought of, and I tried to follow him. It was a very cool thing.

The second verse of "Ain't Too Many of Us Left" that I sing with him is very autobiographical. I was completely and appropriately doped up because I just had two metal hips put in. It's a very violent surgery. Forty-eight hours into that I was really out of it. I was just about to start my rehab. And the phone rang — I was getting calls through the day and well wishes — and it was Neil Young. Amy put the phone up to my head,and I had a great pep talk from Neil I'll never forget. He finished up by saying, "Get well, there ain't too many of us left." I filed that away and knew someday it would be a song.

Sam Moore is a legend, but so is Paul Rodgers in our book, and his performance on "Amy Joan Blues" is fantastic.

I don't know if people know it, but Paul to me is as great a singer as there has ever been. One of my heroes from a very young age with the band Free. Free had even deeper album cuts than Bad Company. Both great bands, but Free was spectacular. On the fourth Grin album there's artwork on the front and back, and if you turn it on the back there's a little stairwell into another dimension; there is seemingly graffiti down into the dimension, and if you hold it up to a mirror it says "Number 1 Paul Rodgers." That was way back in '73 on the back of the Gone Crazy record. I've been a big fan and friend for a long time, and I was very honored that he was willing to help me out.

Let's move from vocals back to guitar. Since Steve rejoined the band you've been honing your skills at dobro, bottleneck, lap steel and other instruments. How has this shaped your songwriting?

Right off the bat I recognized by Bruce's own description it's a two-keyboard band. And certainly you do not need four guitar players. And you've always got Patti on rhythm. So it was an obvious time to challenge myself to become a swing man and play lap steel, dobro, pedal steel, six string banjo — all these other tools in your toolbox for Bruce to draw on. And it is based in songs and the stories that Bruce is telling. He is very authentic in his songwriting. Simulating a pedal steel in a Bruce Springsteen song is not going to work. I became a decent beginner — I doubt I'm going to be a virtuoso on any of those instruments, but Bruce doesn't need that.

It's been a great journey. And one of the great moments from that journey: five years ago I wrote a Christmas song, my first bottleneck dobro piece called "In Your Hands," for my wife Amy. And that led to a duet with Willie Nelson, which never would have happened if I hadn't started tackling these other instruments. The first song I ever wrote on pedal steel was called "Trouble" and was on that same album, Sacred Weapon. Having these other instruments, besides your stock guitar and piano, is a huge growing experience and gives me more tools, not just in the band.

Does it also help in the work you've been doing with Patti Scialfa on her next album?

A couple of months ago Patti and Steve Jordan, who has kind of overseen her last two records, they've got a great studio at home and we started recording some new songs. I don't think there is any timetable at all. I just think Patti finally has started her next record, and I've been deeply involved in her last two. We did some TV shows, took a band on the road. And she is a brilliant songwriter. Her last album Play It As It Lays in particular is so funky and earthy and soulful.

We have this little cool band called The Wack Brothers, which is Chris Carter and Charlie Giordano on keyboards, Willie Weeks or Bruce on bass, Steve Jordan and Patti on the guitar or piano and singing, and me jumping around, the swing guy on different instruments. It's really a beautiful band to work in. As usual she has great songs and a great sensibility about how to present them.

How does Bruce handle being on bass and not being the bandleader?

It's refreshing for him. He's a master musician. The focus is so much on his songs that I think he is underappreciated as a musician. He is a much better musician than people imagine. It's kind of ridiculous that he wasn't in the top 100 guitar players, if you listen to the 3,000 guitar parts he has recorded over the last forty years... but that's Rolling Stone, and it's just a popularity contest and nothing to get too uppity about. He is a very talented musician whether he is playing the bass, or tambourine, or organ, or whatever. It's nice for him to be in the studio and not have to be the leader. Just like myself, one of the gifts for me to be in the E Street Band is I'm not the bandleader. I'm used to being the bandleader — for 43 years, far more than not —and I'm comfortable, but it is really refreshing just to be in a great band. You have a different perspective musically that you don't get to bring to a musical challenge if you are the bandleader. It's nice to take a break from that, including for Bruce.

You've both had very long runs and intersected long before you joined the E Street Band in 1984. In fact, your debut solo album in 1975 had a big influence on Springsteen as he was finishing Born to Run. Indeed, it was Jon Landau who gave it a rave review in Rolling Stone. Did you know that at the time?

It wasn't until the Born in the U.S.A. tour in some backstage scenario that I first heard Bruce say that he and Jon really listened to that record and studied it from an arrangement and clarity point of view and it was useful for that. That kind of blew my mind. More recently, last tour, Bruce and Roy and I went off and did the Spectacle show with Elvis Costello, and Elvis asked me to warm up the crowd with my song "Like Rain," which I did, which is an old favorite of his. And somewhere in that early interview I heard Bruce talking about me and again he brought it up. And it really surprised me. Obviously, it was a great honor to hear that. We all look to get ideas and inspiration and learn. In a way that was a special record. Me and David Briggs had a theme for that and we worked hard but also to keep it live. I'm grateful as hell that that was useful to Bruce and Jon, as god knows they pulled in ideas from many sources including the classic body of work we all grew up with.

In preparing for this interview, we found a quote you gave to Lester Bangs in 1977. You said, "I am 25, and I intend to keep playing my ass off when I'm 30 and way past that, too." Care to update?

[Laughing] That's hilarious. The classic naïveté of youth. Here I am at 60 with two fake metal hips thinking I'm going to go out and kick some rock 'n' roll ass in my own shows and apparently in the summer with one of the great bands in rock 'n' roll history. And what a blessing after 43 years on the road to be able to consider any of those things. Thanks for letting people know about my new record.

Old School is available on CD from Backstreet Records. For more about Nils and his new album, visit nilslofgren.com. Lou Masur is the author of Runaway Dream: Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen's American Vision, available in hardcover and softcover.

Back to the main News page