How to find something fresh to say about Bruce Springsteen's body of work? You could start with a whopping 60 hours of new interviews with key players — musicians, producers, and engineers — which is just one element in the mix for Brian Hiatt's new Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs. How to find something fresh to say about Bruce Springsteen's body of work? You could start with a whopping 60 hours of new interviews with key players — musicians, producers, and engineers — which is just one element in the mix for Brian Hiatt's new Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs.

Just published by Abrams Books in the U.S. and Carlton Books in the U.K., the book is a soup-to-nuts, Greetings-to-High Hopes survey of Springsteen's entire recorded catalog of original songs. More than 300 of them, taken on chronologically and one-by-one.

From early associates to latter-day collaborators, with many that span the years, Hiatt's Who's Who list of interviewees is worth once again typing out: Larry Alexander, Ron Aniello, Mike Appel, Roy Bittan, Bob Clearmountain, Danny Clinch, Cameron Crowe, Neil Dorfsman, Jimmy Iovine, Randy Jackson — and the names keep coming, dawg — Rob Jaczko, Louis Lahav, Nils Lofgren, Gary Mallaber, Tom Morello, Brendan O'Brien, Thom Panunzio, Chuck Plotkin, Bary Rebo, Marty Rifkin, Sebastian Rotella, David Sancious, Toby Scott, Soozie Tyrell, Max Weinberg, and Thom Zimny.

That's on top of interviews the author had already done with Springsteen (five times), Steven Van Zandt, Jon Landau, and more in his 15 years at Rolling Stone, plus transcripts shared by his colleagues. Combined with his own extensive research and insights as a longtime fan, Hiatt has created a rich survey of the Springsteen songbook that is, even for major fans, as enlightening as it is entertaining.

With his book hot off the presses, Brian will be heading to his publisher's office in New York for us shortly, to sign The Stories Behind the Songs especially for Backstreet Records customers. Order now to guarantee a signed copy.

In the meantime, a longread.

In late March, Backstreets editor Chris Phillips spoke at length with Brian Hiatt, delving into the thought process, detective work, close listens, and conversations that informed The Stories Behind the Songs. After a Greetings listening session with David Sancious and a chat with Chuck Plotkin that left him limping, Brian kindly took time for an epic conversation with Backstreets — nowhere near 60 hours, but long enough to dig into Springsteen's 1977 "Star Wars tape" and how Barry White inspired Max Weinberg.

We had a much briefer Q&A with Hiatt in December, but after receiving an advance copy and devouring it cover-to-cover… just like the book, we wanted to go deep.

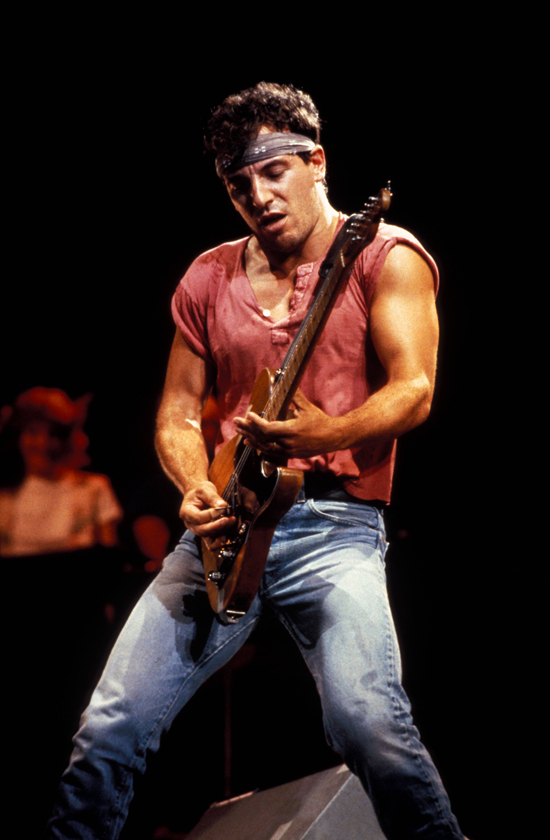

Getty Images / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

Backstreets: I have to say, I love this book. No bones about it. This thing scratches every itch I have — the basic concept of it, as well as the execution. So first of all, congratulations.

Brian Hiatt: That means a lot, coming from the source. Thanks.

We want to talk mainly about the text, obviously, but it's a beautiful book, too — were you involved at all with photo selection?

All credit to the British publisher, Carlton, who put it together. I made some initial suggestions about photos, but that's largely on them, and they did a great job with it.

It's refreshing — they did a good job of finding images that haven't been used over and over.

Yeah, I was very relieved to see that. It helps that Bruce Springsteen is someone who has been photographed a lot, and back when photographers actually owned their pictures. So many artists now are cracking down and trying to own all pictures taken of them — god help the person who tries to do an Ariana Grande book in 20 years.

But clearly the big draw is the in-depth, song-by-song tracking of Springsteen in the studio over, what, more than 40 years. When you were approached by an editor with the idea, was it a no-brainer for you?

I agreed to do it because I didn't want someone else to do it and do a worse job [laughs]. It seemed like an opportunity to do something real. And it could have been something less real and much less revelatory. So that was why I took it on.

Backstreets put together a song-by-song for Tracks, when that came out back in '98...

Oh, yeah — I definitely consulted that...

...but that was just 50-something songs. And here you did it — and more, with all the fresh interviews you did — for the entire catalog. So in a way I can easily imagine it, but in another way it's far beyond. You took it to the nth degree. How intense was this for you? What did your workspace look like?

Oh, man — at home, I had a huge stack of every Bruce book. And then, as I've said, I bought a complete collection of Backstreets on eBay. I had a messy Bruce area for sure. Luckily, a lot of it is digital — at least I wasn't using CDs! But even so, an enormous stack of stuff for sure.

When we talked about this back in December, you were saying that this book that would "hopefully expand the historical record." And it certainly does. I learned a great deal from it.

But there's also a lot of merit in culling and curating facts that were already a part of the historical record and putting them in one place, which your book also does really well. Certain stories we already knew — Stevie arranging on "Tenth Avenue," or [Bob Dylan's] "Series of Dreams" leading to "Living Proof" and Lucky Town — those pieces are important, and they've also been scattered to the winds over the years. So it's a real service to bring those things all together.

It's definitely a combination. I was determined to add to what's out there. I wouldn't have done it otherwise — if I didn't get a sense that people were going to talk to me, or if I didn't know how to get new information or put fresh twists on things that were already out there. I wanted to tell the stories that you have to tell, that have been told, in an interesting way. And also connect the dots between things that are already out there.

You do a lot of dot-connecting in the book.

The more stuff that's out there... in one sense, you become disadvantaged, because so many things have already been told.

In another sense, especially after Bruce's own book and Peter Ames Carlin's wonderful book, you have an advantage — because there are more dots to connect.

Bruce, in particular, had a delightful habit — if you're me, writing this book — of dropping information that pertains to songs [in his memoir] but then not saying that it pertains to a song. It takes a little bit of detective work, and I could be wrong, but there are a bunch of dot-connecting cases where the dots just line up too perfectly.

What comes to mind specifically?

Well, for example, the girlfriend he mentions [in Born to Run] who I believe is actually an inspiration for the song "For You." That's an example of something he wrote about in the book. And you're like, "barroom eyes," wait a second, isn't that... that's her! I don't think I'm that direct. I leave room for doubt. You know, maybe not. But that's a great example.

Here is what happened in December, according to Bruce himself, and then very soon after, we know he has written this new song.

Right. It matches. It could be a remarkable coincidence, or it could be just one of many inspirations, but it's there, and it's interesting.

Another great example, just a small thing, is when he writes in his book about Mongolian gangs — that there really were Mongolian gangs at Freehold High. And that's, of course, a lyric in "Candy's Boy." But he doesn't make that link himself at all.

And then there's "County Fair." I think there is strong evidence that what he is singing about in "County Fair" is actually the experience that he talks about in Born to Run, which kicked off his deepest depression. Again, maybe not... but once you have that information, you might understand what that song is really about.

There has always been a sadness that runs through "County Fair" that's hard to put your finger on, other than maybe nostalgia. But there is clearly something heavier going on than just a fun day at the fair. So to have that line up with the biography — even be explained by that — is very satisfying.

Yes, so hopefully there's a bunch of stuff like that. The whole thing was sort of a giant puzzle to be put together. And luckily, I had pieces from a lot of sources.

Including your own — even before you started doing any new interviews for the book, you had interviews already in the can, from your years at Rolling Stone.

I had five previous interviews with Bruce, and interviews with other people as well. Plus transcripts from generous fellow writers and a lot of other stuff: Mark Binelli, David Browne, Anthony DeCurtis, Andy Greene, and Joe Levy all shared transcripts with me, which was very helpful. Everyone was so helpful. Even someone like Cameron Crowe, giving me the story of "Secret Garden," which is so great.

I've talked to Steve a bunch of times over the years, talked to Landau, people like that. The story you just mentioned of Steve Van Zandt doing the horns for "Tenth Avenue Freeze-out," there's a good example. Luckily, as it happened, I talked to Steven 14 years ago, for the reissue of Born to Run, and he told me another version of that story. So I had a semi-fresh take — that's new, it had never been printed anywhere.

And then I consulted any lyric sheets I could find, some fairly rare ones can be dug up. Bootlegs, any bootlegs were tremendously useful. Prior interviews, deep newspaper archives...

As you mention lyric sheets, the fact that you got into discarded lyrics that didn't make it into "Santa Ana"… That's deep. That several levels right there.

Hey, listen, you've got to be thorough [laughs]. Exactly. You know, the deep study of [Bob] Dylan has sort of always been a thing. Dylanology, obviously, has been a thing since the early '70s — even though it started with a dude going through his garbage, which I do not support. But I feel like there is room for that with Bruce as well. And if he eventually lets more lyric sheets out there, stuff like that, I think there is even more room for this kind of thing. Because going through drafts is just fascinating. It can be very illuminating.

For example, "Lost in the Flood." If you look at early drafts, certain aspects of that song become much clearer. For some people, it may have always been clear that the descriptions in the song are through the eyes of the returning soldier. That was not always super-obvious to me. But if you look at the discarded lyrics, it becomes completely clear that this — the "countryside burnin' with wolfman fairies" — this is a returning soldier talking about the hippies he is seeing.

Bruce had serious lyrical sophistication even on his first album. Some of what seemed like nonsense lyrics was not at all. He was actually writing (on his first album!) in the third person from the point of view of the character. Which is a fairly sophisticated literary technique — that he probably reinvented from scratch, having not done, at that point in his life, a ton of reading. It's basically free indirect style, which is very sophisticated stuff.

Which is amazing, considering how green he was. But you also don't get lost in the lyrical weeds or anything, which would be easy to do with multiple lyric sheets — you're writing about the music and the recording, too.

Yeah, it was interesting to dig into the arrangements, and the playing — thinking again of the first album, to listen what's actually on the album. Because I think for a lot of real Bruce fans, those versions have been eclipsed by the live versions just because it's such a skeletal album.

"Lost in the Flood" is a good example, again. You write about the birth of the songs— the recordings, their origins, their meanings — but sometimes you also track the lives of the songs. In the case of "Lost in the Flood," you write that the song sort of reached its full potential 30-something years later.

That aspect... it's in there. In order to keep some focus in the book, I didn't get super, super into the live evolution of the songs, because live Springsteen has been much more thoroughly covered than studio Springsteen. So I tried not to go crazy with that, but there are some cases, like that one, where you just have to mention it.

But with Greetings as a whole, that's an album that I listened to more for the book than I ever had before — and more carefully. It's not a fully realized album, really. For the most part, you would rather listen to a live version of "Lost in the Flood." You might rather listen to the solo-piano "For You," or a live version of "It's Hard to Be a Saint." I don't think a lot of people are rocking the Greetings album over and over again. I don't know if you disagree.

No, I'm with you. It has its proponents, I know, but for me it's the album that I've played least of all of them.

Right, the songs are great, but... we know from our Dave Marsh studies early on that there always was this push-and-pull with that album, as far as being acoustic or not acoustic. But as I really dug into it, I hadn't realized this is actually true: astonishingly, there really is no electric guitar on that album other than on "Blinded by the Light." Like, literally, none. Other than Steve Van Zandt kicking the amp at the beginning of "Lost in the Flood."

[Laughs] I remember Stevie being cagey, in a funny way, about his one contribution to that record.

Which, by the way, maybe crazily, but I'm convinced that was a nod to the 1967 Tim Buckley antiwar song that has the same kind of start, and it's supposed to be an explosion. Bruce was a huge Tim Buckley fan, and it's a very unusual way to start a song.

But anyway, it's funny to have listened to that album so many times in the past and never really put it together: oh, wait, there is literally no electric guitar other than "Blinded." It's wild. Your mind kind of puts it in there! But you go back and listen to it, and you realize he was truly held back from using electric guitar except on that one song.

You also hear how much [David] Sancious was playing on that album — it's a lot. When I was talking to Sancious, I played him a bunch of his little licks from Greetings, which he really doesn't recall — he doesn't seem to have listened to that studio album in many, many years.

Well, I was going to ask you: based on my reading of the book, you actually sat down and listened to stuff with Sancious, didn't you?

Yes. Well, over the phone, at least. I did a bunch of interviews in person; in this case we were on the phone. But I just played him a bunch of stuff over the phone from the first two albums, and he was fascinated to hear some of it. Especially Greetings — he just was not familiar with what he played on that album. He would listen to it and say, like, "Oh, wow."

If you zero in on it, there are some really cool bits. Like what Sancious plays at the beginning of "It's Hard to be a Saint in the City" — the studio version is really, really cool. And again, as he said himself, he had basically no memory of it. But listening to it, he really dug it.

So not only were you writing song-by-song, you were also taking some of these people through it song-by-song.

Right. Like Appel — it was really interesting to go through things song-by-song with Mike Appel. Even as much as he has talked about this stuff [over the years], to really go through it and have him rethinking some of his production. Like that wonderful lick at the beginning of "Blinded by the Light" — Appel told me that, come to think of it, he should've stopped the song in the middle and had that riff come in again, because it's a shame to have it for just one time. Little things like that were fun.

It was interesting to see points where he and Bruce disagreed on whether to do something along those lines. And that recurs throughout. It's just fun to hear when somebody like Ron Aniello makes a suggestion and Bruce says, "I will take that into consideration." And of course, it never comes up again.

You certainly learn two things at once: you learn that a bunch of the stuff is perhaps more collaborative than you might have thought; at the same time, there is no doubt about who has always been in charge.

Getty Images / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

One of the arcs of the book is how significantly Springsteen's studio process has changed over the years. That's one of the fascinating things about reading this cover-to-cover. I mean, obviously, you can open it up and just read about "American Skin," if you want. But taking it from the beginning through the end, that's a major through-line. Being fresh from talking to so many of these guys, can you describe that arc?

At the very beginning, Bruce is... unburdened by doubt. The first two albums, he's just going. Especially on the first album, he just recorded. He just blazed through it. And then with Born to Run, the torture begins.

The torture gets expressed in different ways. On Born to Run, it was the torture of rewriting the songs and finding his sound. Because that's really what he was trying to do: he was trying to find his definitive sound (which, of course, he did). And the torture was every detail of that one set of songs: rewriting over and over again, the lyrics, the arrangements. It's fascinating, of course, to track the jazzier, Sancious/Boom Carter versions of those songs against what they became. It's the starkest transition in Bruce's catalog. So this was torture over the details — he knew pretty much what songs he wanted on there, but it was about getting them right.

Darkness combines two kinds of torture. They can't get the sound they want in their heads, that's A. And B, there are way, way too many songs. They don't know what the album should be. They don't know which songs should be on it, and they can't get them to sound right. It's the unique point at which two pain points combined. They're recording a million songs and torturing themselves over the sound.

Then on the The River, they don't give a shit about the sound! Well, no, that's an exaggeration. They were finally in the right studio — the right studio being the Power Station. I think there is a small glitch in that chapter where the Power Station is referred to as the Record Plant... I will be fixing that. It's actually a correction that I submitted, but somehow the correction didn't make it in the first edition — there are a few things like that, just glitches. Those things drive me more than a little nuts, but I do hope eagle-eyed readers will be somewhat forgiving. (Oh, speaking of eagle-eyed, I’ve seen people get confused by the unusual font on the page numbers, so if you don’t look closely, the zeroes can look like eights. However, for the record, all the page numbers are perfectly correct!)

I know how it goes.

So yes, the Power Station. And they got the sound in the first song, "Roulette." Right away, they found this much more exciting, live sound.

That was all about recording the band, right?

Right, recording the band, and they wanted a live, messy sound. So once they got it right... then they would run in and just record. This is according to Neil Dorfsman. They would come running in, just as it was set up, before Neil could get everything sounding exactly as he wanted, they would just start recording. Because it was just about generating audio — getting away from this perfectionism of trying to nail any individual song and just blasting out stuff. Then the torture really becomes, what is the album? We have a million songs. What is the album?

For Born in the U.S.A., same thing — at least as much so. The Born in the U.S.A. sessions are just mind-boggling. In Marsh's Glory Days he makes it clear, there were so many versions of what Born in the U.S.A. could have been. They had so many different track listings.

Toby Scott told me that they were sitting around trying to do some version of a sequence for Born in the U.S.A. Bruce wasn't even in the room. And Mick Jagger comes popping into the studio. He's like, "What're you doin', boys?"

They say, "We're trying to get a track listing for this album."

Mick is like, "Is there a hit on it?"

And they say, "Yeah, we got one."

And he says, "Just do that and 11 other songs."

[Laughs] So that, of course, was never the Bruce approach. And here I've got to give a nod to Clinton Heylin, who did the very valuable work of getting the Sony Studio records for his book and its companion book that dealt with Bruce's studio stuff up until 1984.

E Street Shuffle — that's a goldmine, for sure.

A very different kind of book, but very useful, just to know when Bruce recorded everything. You go through the Born in the U.S.A. sessions, and it's just relentless. They would think they were done, and then he would just keep going. And going. To the point of being truly mind-boggling. And then you consider that "Dancing in the Dark" was recorded when they already were mixing a version of the album... it was that kind of torture.

Now, to back up a second, you have Nebraska — which in a way was the easiest experience ever. The actual recording of it. And it begins this thing from Bruce of, "I don't really like the studio at all." You know, "I'm suspicious." It may be as much symptom as it is expression of his discomfort with the studio. And so Nebraska and Tunnel of Love are of a piece in a way that people may not realize. As Chuck Plotkin and Toby Scott both told me, it's just an extension of "I'm doing this by myself."

Bruce told Toby, "I've never been so happy recording an album" as for Tunnel. Because suddenly he doesn't have to have anyone else's opinions. He doesn't have to deal with anyone else's personalities. He's just doing it.

Obviously, he brought people in to do bits. Max described to me this amazing image: Mighty Max, sitting there in this little, un-air conditioned room above Bruce's garage in Rumson, New Jersey, hitting a snare drum. Just hitting a snare drum. And the great thing about Max is, Max really enjoyed the experience! First of all, he has a real humility; he just wants to do what is needed. And number two, it was interesting as the drummer to just be him and Bruce. That's not usually how things work.

From there on, what really happened is that the line between demo and album blurred forever.

That's probably the point at which I've had less of a sense of how the albums came together.

It gets really confusing. A lot of stuff up until Brendan O'Brien is essentially home recordings, either enhanced or not. Even Human Touch. For Human Touch, Roy and Bruce made these very, very detailed demos, and then they would often have musicians play over the demos. And then they might redo them. And then they might choose between the version that was played over the demo versus the version that was redone.

So one of the problems with Human Touch, honestly, is that you have musicians who are so fantastic — like Randy Jackson, who I talked to, and Jeff Porcaro — who might be too good, which is what more than one person said to me. Not only are they too good, too facile on their instruments (though Randy, of course, denies that there is any such thing), but they are playing perfectly, over perfect demos. And that's how you get a slick-sounding album. That's kind of what happened.

Then Lucky Town, of course, another homemade album. And that goes all the way up to the 2000s, before Brendan [O'Brien] returns them to a live experience on The Rising. But there continued to be plenty of overdubbing demos, especially on Devils & Dust.

Toby once said to Bruce, apparently, "We don't make demos, we make masters." In the sense that if you are recording it professionally, and playing as well as Bruce Springsteen, there's no such thing as a "demo," per se. Which I think has been his operating philosophy.

Back with Brendan [for Magic], there's still a lot of playing live with the E Street Band again, but definitely still some release of overdubbed demos. And then with Ron [Aniello], you have the full blurring of the line between demo and not. Because the piece-by-piece, ProTools recording that he does with Ron, for the most part, is very much like building off of what could have been a demo. Bruce comes in, strums a thing, sings something rough, and then they're just building on top of that. Ron played me a bunch of that stuff, which is really cool.

It seems like record-making really became a different kind of exercise by that point. By the time we get to Ron, and I don't want to overstate it, but seems like it's as much about digital editing as it is about performing. With all the overdubs it's like putting a puzzle together on the computer, the way Bruce and Ron seem to work.

I don't know if it's so much digital editing... it's more the ability to record a bunch of stuff and choose. I mean, Bruce's vocal performances are still Bruce's vocal performances. But, yes, with Ron being on board — essentially what seems full time, at Bruce's Colts Neck studio — Bruce could come in, record something, and then just build on it. That became a thing with Wrecking Ball. It was a new way of making music. And Bruce himself did all those samples — for example, on Wrecking Ball, that was Bruce bringing in samples, for the most part, and Ron cutting them up.

Which is really interesting — I guess I had imagined Ron bringing the sampling to the table. I forget which song it is, but you noted one where Bruce had basically written something over a sample and then brought that to Ron.

"Death to My Hometown." Bruce took an Alan Lomax recording of a chorus, singing "The Last Words of Copernicus" — which is an old folk melody that, if you trace it back, was probably Celtic in origin. So Bruce found the Celtic-sounding part of that, looped it, and wrote "Death to My Hometown" over it, apparently.

Rex Features / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

It's fascinating to think about the different ways Bruce has written songs — he's talked about challenging himself with genre exercises, writing songs on bass in the Human Touch era, to here, where he's writing a song over a sample.

Oh, yeah. I loved isolating the songs that are from the "bass album," that was really fun — just realizing these are all of a piece.

That comes through nicely in the book. Again, there's the balance of your own observations and the new information that you bring, triangulated with stuff was that was already "out there." A lot of which, by the way, I may have forgotten or never known in the first place. Some compelling things, like the fact that Bruce had a poster of Peter Pan above his bed in 1975.

Right! That was in some interview with him back in the day. But I'm not sure that anyone had made the connection and been like: oh... Wendy. Of course. "Born to Run"… Wendy.

Exactly. Another one was the rabbi at [Marc] Brickman's 1979 wedding saying — I wrote this down — "Getting married was 'the first step towards making dreams and hopes a reality.'" I feel like I've heard that before, but I don't know where.

That one goes back to Dave Marsh. I have to say, his books [Born to Run and Glory Days] were very important to me growing up and a big reason why I do this. His Who book as well. Going back and seeing how much information he really nailed, nailed in both of them, is really impressive.

Very much so. So much of what we know, for a long time, we knew only through those books. But I will also say that, last time I read Born to Run and Glory Days, the 2016 River Tour had not happened, nor had that [The Ties That Bind] documentary. So that quote from the rabbi would not have resonated with me in the way that it does now — because decades after that wedding and The River, Bruce is still talking about how much ideas like that impacted the album.

Right. A lot of stuff resonates differently, for sure.

I'll tell you, I never would have made a connection between "Candy's Room" and the Love Unlimited Orchestra.

That was Max! I thought that was so funny. I couldn't believe it. Because when Max has talked about that song, he always talked about what he does on the snare throughout. But I was like, "Well, that's really cool, too... but for me, what about the beginning on the hi-hat?" And he's like, "Oh, yeah. That's because it sounded like Barry White to me, when Bruce was talking." [laughs]

That's hilarious!

Hilarious! And fascinating, because you don't think about these things. You can be like, there is no way that anything on a Barry White record ever made it onto a Bruce Springsteen record. And it's just not true! Everyone hears everything. Now, it's possible Bruce never knew this [laughs]... because it's almost a goof on Max's part. But it obviously works perfectly. It could even have been a subconscious thing: "Oh, he's doing a spoken word thing, why don't I..."

You can almost hear Barry White doing it. "In Candy's room, baby, there are pictures..."

Yeah, I dug that a lot.

And it's an example of just how many song references run throughout the history here. I mean, the book is kind of like a rock 'n' roll history lesson, in terms of their referencing of older songs during the process. For "Backstreets" alone, you've got "Running Scared," Blonde on Blonde, "Madame George," Ricky Nelson's "Hello Mary Lou" — all these songs that they either were inspired by or thought about as they were recording. In a way, that's just how Max Weinberg talks and thinks about things, I think, but it also points to this entire other language that they all had.

The shared references and depths of references among all these guys are remarkable. I mean, I'm younger than them. So if Max says "Badlands" sounds like the beat from Paul Revere and the Raiders' "Hungry," that isn't jumping into my mind. But it does for them. And it turns out that "Badlands" does sound a bit like "Hungry." Because they were drawing not just from the stuff that is still famous and played on the radio all the time. They knew everything that was ever played on the radio — even if it was just for a week in 1961.

And it's not just old stuff here, either. I was pleased to see a mention of Chris Whitley. If you were seeing shows at the time, when Bruce was so into Chris Whitley — 1992-93, and again on the Reunion tour — hearing "Big Sky Country" over the P.A. is very memorable. So to see you make the connection between Chris Whitley and a song like "Big Muddy"...

Again, I could be totally wrong....

But no, it resonated with me, like that could very well be where that sound was coming from. Lining up the years, it makes total sense.

Exactly. Of course, it's hard to say: was he inspired by Chris Whitley? Or did he like Chris Whitley because it was in a similar vein as what he was doing at the time? You know what I mean?

The same thing with the song "Lucky Town" and Social Distortion. "Lucky Town" really could be a Social Distortion song. But was that because he'd heard Social Distortion already? Or did he like Social Distortion because it sounded like something he was going for? Who's to say?

Getty Images / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

As opposed to a narrative, which would be challenging enough to write for a book this size, you have what amounts to 300 articles. Some bigger and some smaller, but each one has its own opening and conclusion, and choices of what to include and what to leave out. Certain songs had to have a lot, and other songs don't require it. How did you think about how much you wanted to say about a particular song, and the correlation between that and how "important" the song is?

A lot of it had to do with whether I had something fresh on a song. With some of the more important ones, even if I didn't have something new, you still have to tell the story. The funny thing is, the more "important" the song, the more people remember it and might have something to say about it.

Other stuff, like the outtakes of the outtakes from The River — you know, the Ties That Bind stuff? — no one remembers recording those! [Laughs] They do not! They remember the Tracks stuff a little better, but the [more obscure] stuff on The Ties That Bind — "The Man Who Got Away," "The Time That Never Was" — no one, not the musicians, the engineers, the producers, no one remembers that stuff. Because with those River outtakes, they might have played those songs once or twice. Some Darkness stuff as well: once or twice.

"The Iceman," that's one of my favorite songs of all time. But Bruce, famously, didn't remember recording it. And no one remembers playing it! Because they basically played it one time in 1977 and moved on.

And the rest of us who were trading it around for 20 years, we've heard it a million times.

Right. Bruce fans have known it better than any of these people. They don't remember making it. So it became comical. Something like "Chain Lightning" — everyone was like, "Nope." They don't remember making it at all. So the shortest entries, predictably, are for things like that. And it is what it is.

Though there were certain songs... like "White Town." Man, I listened to a ton of early versions of "White Town" that are actually fascinating. Bruce worked really hard on "White Town"! [Laughs] That was interesting for sure. All those dead ends in his work, the fact that he would just beat his head against the wall on a song like "White Town" — which no one heard for many years and even got lost in the shuffle when it did come out. It's one of the better songs on that disc, but I've not heard anyone talk very much about it. It's just weird — at some point he definitely had a lot of hopes "White Town" [laughs].

It's clear that you listened to a lot of studio outtakes for this — and not just the unreleased songs, but early versions, different takes. For "Kitty's Back," you note a recording where Bruce originally played the horn part on the guitar — a lot of nice tidbits like that. What were you digging into, outtake-wise?

There is so much out there, you couldn't possibly get every bit of it. But basically, if there was an earlier version of the song either played live or bootlegged in the studio, I was going to try to listen to it.

This is stuff that's out there but hasn't been very closely examined. The first time he played "Rosalita," for example, a truly bizarre live version from February 1973, where there's a bit of "Fun, Fun, Fun," by the Beach Boys and little nods to James Brown and Wilson Pickett. That is so weird. There's so much to dip into, between live and studio bootlegs — the volume is just tremendous.

I'm sure Bruce hates this. I'm sure Bruce hates the fact that these early attempts at songs have been bootlegged. It does feel like a bit of a violation, I have to say. If you have ever written a song, the idea that someone actually put out the bit where you're humming dummy lyrics and trying out lyrics over and over again, the idea that all of that is available? It feels like a violation of his artistic privacy, on the one hand. But on the other hand, if you are writing a book like this, it's tremendously valuable. So I have mixed feelings.

Sure. But it is valuable. What else did you turn up along those lines?

"Born in the U.S.A." is fascinating. I didn't realize there was a version where he talks so directly about Richard Nixon. In a way it just seems like private venting — he goes, "They should have cut off Richard Nixon's balls." That's an actual thing he's saying in a version of "Born in the U.S.A." — that's real.

And then an example of a crazy discovery: there's one of Frank Stefanko's pictures, a 1982 Nebraska picture in Bruce's house. You can see by his bed that he was reading a book called Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the Destruction of Cambodia [by William Shawcross]. It shows that he wasn't advertising everything he was reading, you know? You might think so, but there's plenty of stuff he was getting into that he wasn't publicly talking about.

Right. We know about the Woody Guthrie bio, because he talked about it, but...

Exactly, the stuff that was in the narrative. But yeah, when he got into Vietnam, he read a lot about Vietnam. So he was pissed at Richard Nixon, understandably. There are actually two Richard Nixon anecdotes in the book; the other one is that Bruce got punchy while singing "Cadillac Ranch," according to Neil Dorfsman, and he started singing the final verse over and over again in a Richard Nixon imitation [laughs].

That was bizarre.

I know! I don't know if you can draw a lot from that, but it's really funny... and I'm just dying to hear it. You can kind of picture it. I hope the world can hear it one day.

It's funny — I made a list here of some of your interviewees that I want to talk to you about. And under Neil Dorfsman, I just wrote "Bruce singing 'Cadillac Ranch' as Nixon." And there you go.

So let's go from there. You talked to so many important players for the book, I'd love to get your overall take on some of them. It seems like Chuck Plotkin was really forthcoming.

I thank Chuck a billion times in the book, because when you're starting something like this, you don't know if anyone is really going to talk. Someone has to be first. And that's tough to be first — as opposed to, this person talked, and this person talked, so I'm going to talk. But with Chuck, I reached out to him, and I included my last Rolling Stone cover story with Bruce. He called me, and he was like, "You know, I really liked that interview, and I figured I could talk to that person."

Chuck really has not done much like this. He talked to Dave Marsh and Peter Carlin, and that's pretty much it. He hasn't done a lot of interviews. And you know, it's emotional territory for him. He loved his years with Bruce, and it's a really hard thing to be in that camp and then not in that camp.

We went through his entire time with Bruce, and it was a real journey. I just loved talking with him — and you can also see why he is a guy that Bruce and Jon would talk to for hours, because he is such a thoughtful person. He has so many thoughts on everything and was great sounding board. He had ideas of his own. He had critical takes on things.

The first time Chuck shows up in the book, it's crazy. Bruce tells him he wants "Adam Raised a Cain" to feel like... what, cutting from a picnic to dead body under a tree?

Yes — that's actually from the Promise documentary.

Is it?

Yeah — but reading it again... it almost hits you more reading it than hearing it.

Totally. And then the really crazy thing — and pretty risky, for a new guy on board — is what Chuck did to get that effect.

What he did is fucking wild: he detuned Roy's piano! Roy's beautiful piano part —and I'm pretty sure Roy had no idea, by the way — Chuck fucked with the piano to make it slightly out of tune. He used an Eventide Harmonizer, a very early piece of digital equipment and not the kind of thing you would think would be on a Bruce album in the '70s. And then he was like, "Okay, they are definitely not going to want me to mix the album after I do this." But they loved it.

So Chuck was just amazing. We talked for a solid ten hours of recorded conversation. In my entire career, I'm not sure I've ever done more interviews with a single person than I did with Chuck for this book. One night I was sitting and talking to him for so many hours in a row that my leg cramped up and I actually had a limp for two days.

You got to get up and walk around, man.

Yeah, exactly. I was just really focused — we were really into the good stuff. And that's the broader point, is that Chuck and a lot of these other people, they had stamina. And that is what it takes to hang with Bruce. In general, because of how Bruce works, you've got to have this focus, and stamina, and patience. And every single person I talked to had that.

It was fascinating to read that he edited out the bridges on "Point Blank," without asking, and that's basically what secured his position on the team. That was, again, a risky thing to do.

Chuck had ideas. Editing instincts — what to leave in, to get rid of. For "Point Blank" he heard those bridges as extraneous. And Bruce was like, "No, no, I decided that it needed those, and I wrote them after the fact." And Chuck was like, "Yeah, well, they sound like you wrote them after the fact."

So I think that kind of insight into Bruce's creative process won them over, and he was basically promoted to full member of the production team with The River. It was also things like speeding up "Hungry Heart." Bruce was like, "It doesn't sound good." And then months later he was like, "This is too slow."

Right! I knew the speed had to be part of the "Hungry Heart" entry, but in my mind it was just a tweak and then done. There's more to that story that's fascinating.

At the time, Bruce had producers who were not your usual producers in rock 'n' roll. With someone like Chuck and someone like Jon Landau, it was almost like having in-house rock critics. They were seeing things not only in the sense of, "Oh, this needs to be a little faster" — they would do that too — but also like, "Thematically, this isn't working," Which, for the most part, is just not the way the rock producers work.

But that's how Bruce was thinking, and that's what he wanted to hear — at that time. Later, with Brendan O'Brien and Ron Aniello, they never had those conversations — never —about the themes or the lyrics. It was just about getting the music right. Which is interesting: different things for different times.

So let'stalk about Ron Aniello. He brought you into the Colt's Neck studio, yeah?

Yeah. Obviously, you don't get to go there if it isn't approved by the Powers That Be — we weren't doing anything illicit there. I'd been fortunate enough to be there before; I interviewed Bruce there. But Ron was fantastic, and he kind of showed me how the songs were made. It was a little bit like Home Alone, because we were there, but Bruce wasn't. But Ron is used to that. Ron comes in there and works every day. On what? He is not at liberty to say! [laughs] But he's there, and it was fascinating to dig deep on those albums.

Ron is very much a music guy. He is about sounds and arrangements and riffs, and he has a good memory for all of that. He is an incredibly talented producer, engineer, musician — and musician in particular. As we know, as Bruce has said, Ron played a lot of stuff! Sometimes they were really a two-man band. Ron can play a bunch of instruments. If there's a wonky guitar part, Ron could just replay it.

And there's also his editing facility. I love that story about him splicing together Clarence's posthumous solo for "Land of Hope and Dreams" — making something out of nothing, in a way — and making Bruce cry.

You do come away understanding why Ron is in Bruce's orbit — because this is a guy who can do a lot of different stuff. Of course you would want someone like that helping you make your music.

Bruce has a home studio, and Aniello basically becomes his home producer, right?

Yeah, listen, he's got an in-house producer. This beautiful studio, with a producer right there. And that's why recording becomes less stressful.

You mentioned that Aniello has the demo tape of Bruce rapping "Rocky Ground." Did you get to hear it?

He would not play that for me. He thought better of it. But it does exist.

Getty Images / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

Bob Clearmountain. The first moment in the book when I was like, okay, I'm really going to dig this, came before you even got to the songs. In your introduction, you have that quote from Clearmountain, saying that Bruce calls his basic rhythm guitar parts "the primal scrub."

Yeah.

That alone is just cool to know. And Clearmountain, like Plotkin, is not somebody we hear from a lot.

Bob Clearmountain is such a great guy. One of the greatest mixers of all time — and has anyone's name ever better suited their profession? I just love what he does.

We talked in person, and the first thing I said to him was, "One of the things that made me realize I need to talk to you was watching the Blood Brothers documentary again, and that scene in which they all vote on which version of 'Secret Garden' they should put out." In the movie, they have that vote in front of Bob. I was like, "Boy, there must be a million stories like that."

And he says, "No, that's literally the only time that happened." [Laughs] He is like, "No, there is literally only one story like that."

But there certainly were interesting things and choices that came up. Like "Tougher Than the Rest," where Bob said there were two solos to choose from. One was just a [typical] "Brucey" solo you can imagine, a higher-pitched thing. And then there was the low, twangy thing. Bruce was a little scared of it. But Bob said, "No, you have to do the twangy thing." That's the one.

The "Tougher Than the Rest" entry was a fascinating read. I had no idea — it's right there in the title, of course I can imagine it, but I didn't know that it was originally a "Real Man"-type song.

Talk about hiding in plain sight — neither did I. But you know how I found that out? Because it's right there in Bruce's book, in Songs. There's a whole lyric sheet in the Songs book, an early version of the lyrics right in there. So again, even for people like us who already knew a bunch of this stuff, there's just too much data to absorb! But there it was — he reprinted that lyric sheet.

And again, that's a part of the value of this book. The fact that you did that work, went back through to find things like that, and put it all in context.

It's funny, in Songs your mind just kind of treats it as a photo, so maybe you don't read it... which was probably the case with me. And it's kind of hard to read his handwriting anyway. But there it was. It's worth looking at — it's pretty funny, actually, the original "Tougher Than the Rest."

I bet. I mean, that's one strain of his songwriting I'm not really a huge fan of — I know I'm not alone — from "I'm a Rocker" up through "Real Man"... the Rambo-type references... but he seems to love doing that from time to time.

I'm looking at the lyrics now: "They want a King Kong Bundy or a real Tarzan...." and "if you want a Mr. Rambo" to something, something, "be my guest," [laughs]... It's right there in [Songs]. It says, in the caption, "Originally written as a rockabilly song." Page 197 of Bruce's book, hiding in plain sight.

The other thing about Clearmountain is that he did some tracking at the very beginning of The River. He wasn't just the mixer. He recorded "Roulette." He was able to talk about that — and there was a funny story about how he wasn't used to being in the studio, so he was like, "Oh, that sounds fantastic! You going to release it right now as a single?"

And everyone was like, "Shh! Shhhhh!" Because it's the worst thing you could say! That's pretty much how you can assure that the song doesn't get released for a long time.

I also like the tidbit you got from Clearmountain — that "Glory Days" has Bruce's favorite snare sound of all time.

It was fascinating to get into snares with Bob. Because Bob actually had to avoid people thinking that was his thing, those enormous snares on Born in the U.S.A. That was him giving Bruce what he wanted. But when he was mixing [other artists'] records for a while, people would say, "I don't want that big snare." And he would say, "That's fine! That was what Bruce wanted." That was very much a Bruce desire.

But yes, for years they went and replaced snare sounds with something like the "Glory Days" snare. If that is Bruce's ideal snare, they would have that as a sample. It might be on Tunnel, it might be on the Live/1975-85 album — it was pretty easy, even back then, to do a kind of find-and-replace for the snare.

Did you talk about that with Max at all?

Yeah, he says that there is not as much of that going on as you would think. I mean, everything he played was live. Occasionally they would go in there and replace sounds — I don't want to make it sound like they were replacing Max's playing. But, certainly, on Live/1975-85 that is happening. Everyone knows that [laughs]. All you have to do is listen to it.

But it's fascinating just how much they are replacing parts on demos, and choosing between the original and the new thing. I guess that process really started with Nebraska — what do we keep from this original, inspired take, and what parts do we replace? And the ability to do that.

It's this weird discomfort with the studio, with the artifice of the studio. It's really all the way until Working on a Dream before he decides, I'm going to overdub a ton of stuff and not worry about it, really try to make a studio thing. Of course, for the fans, that was a controversial moment. But in general, I think it's all about privileging the raw.

Speaking of Working on a Dream, let's talk about Brendan O'Brien. He really seems to shoot from the hip — in a good way.

Brendan was fantastic. Again, as with talking with all of these people, I really felt like, "Oh, yeah, I would love to be in the studio with this person. This person is as cool as hell." You really get a sense of that. And Brendan was opinionated in the best way, in the sense that he would say — whether to me, on the record, or to Bruce at the time — like, "Not my favorite song."

That was always my sense, talking to people about working with Brendan: he's not a yes-man. Not that I'm saying anyone else is, but there were songs he wasn't crazy about, starting with The Rising. He is not crazy about "Let's be Friends."

I love how no-bullshit he is about that.

There are songs that I like, where Brendan would say, "Really? I'm not sure about that one...." And it's funny to realize that "Let's Be Friends" isn't really a Brendan O'Brien production. It's actually it's a Toby Scott thing. What Brendan said about "Let's Be Friends" is: "I will just say, I do remember that one. I'm going to leave that one right there." [laughs] That was his entire quote about "Let's be Friends."

And then there's Bruce's response as to why it was going on the record anyway — when he basically said, "I don't know when I'm doing this again, so all the songs are going on the album." And how different is that from the old days?

Exactly. Brendan wanted a shorter album — he wanted an 11-song album. And Bruce was like, "You know, you're probably right. But I don't know when I'm doing this again, so we're putting them all on there.

Which just sounds like he wasn't sure [about the future]. It had been a while since he had done this.... and it could have gone either way. It shows the contingency of everything. If things had gone a slightly different way, maybe that would have been the last E Street Band album for a while, you know?

I also loved Brendan talking about working with Danny, who was definitely a real character, and making Danny double his parts — which was the least "Danny" thing you could possibly do. It just goes against everything Danny, to make him precisely double his part. And yet, he did it.

That makes me think of Tom Morello actually doubling his entire freaking solo for "Joad." That's amazing to me, that he can do precisely that same thing twice.

That is truly, truly wild. And Tom was a big factor in the later stuff, no doubt. He was just awesome to talk to — and it's just still fun to think that if you are doing a thing on Bruce Springsteen in the studio, you have to talk to Tom Morello. That still kind of blows my mind, honestly [laughs]. As everyone says, it's just not something you could have predicted in '92.

I want to ask you about [Darkness assistant engineer] Thom Panunzio. For all the things in your book that I'm not sure whether it's new information, or something I should have already known — or if you found it in Songs — the whole "Star Wars tape" thing from Thom, that's got to be new, right?

Oh, yeah. This is another thing where there are dots to connect. We knew that there was a tape: a tape from the first day that Bruce and the E Street Band went into the studio for the fourth record [in 1977]. And by the way, it's super-fun to realize that the moment that they settled the lawsuit with Appel — you can look at the dates — within just a few days, they were in the studio. They were not messing around. The moment they could, they were off and running: "Let's go, boys."

So they're in the studio, and they basically blazed through ten or so songs that night. And then there were a couple very soon after. That's well known. Even in the notebook that was in The Promise, they reproduced a sleeve of that tape.

But what I didn't know — and I just love this — Thom Panunzio told me that everyone called it "the Star Wars tape." And the reason everyone called it the Star Wars tape is because Star Wars had just come out! Which I love, that Star Wars was even on their radar screen. But of course it was, right? It was '77! [Laughs] These people lived on Earth! They knew about Barry White and Star Wars.

What's delightful is that you know about this tape, and then you find that Bruce told my colleague Mark Binelli (one of the wonderful people who shared transcripts with me) — who knows why he was even talking about it in an interview about The Rising — suddenly Bruce says, "Yeah, we recorded ten songs for Darkness that I thought was an album, but then I went back and listened to it, and it wasn't an album."

The Star Wars tape! It had "Candy's Room" a.k.a. "The Fast Song," it had "Breakaway," it had "Rendezvous," "Because the Night," "I Wanna Be with You," it had an early version "Darkness," "Outside Looking In," "Don't Look Back...."

It's dated 6/1/77 on the label that's in the Promise notebook. Panunzio thinks that was much more commercial album. And it was — of course it was — it had "Because the Night" and "Rendezvous" on it! [laughs]. And "I Wanna Be With You," which is super fun. So it was a much more fun, light record. And of course, Bruce could never let that stand.

Think about that weird alternate universe where he puts that out and then follows it up with The Ties That Bind.

It's very similar, actually. It's very much like a Ties That Bind version of Darkness. Bruce felt there wasn't enough content there, that it was just kind of surfacey. He told Mark Binelli that he was heartbroken, because he thought for once they would go in, and.... They had been working since '76, they had all these songs ready, the band was blazing, and maybe this time they would just have the record ready. And he was very disappointed to realize that they didn't.

That said, Thom and everyone else who had that tape thought it was fucking great.

You talked to so many people — some are names that, honestly, many of us will only know from liner notes. But given that we can't go through all of them, I at least want to bring up Toby Scott. He has a wealth of knowledge.

Toby, hilariously, was the final person I talked to for the book. The book was basically done, almost already in production. But I went through everything with him. Toby has an amazing memory and knows everything. And for something like Lucky Town, he is one of the only people who can shed any light on it. He is discreet about what he says — he was a constant presence in front of Bruce for many, many years, so he's only going to say so much — but he was great.

My favorite thing to talk about with Toby was breaking down the vocals that Bruce re-records for songs, outtakes, things like that for box sets. Bruce's modern vocals, compared with his vocal styles in different eras. If it's just patching a line in a '78 song or something, Bruce can and will do it in the original style of the song. But if he's recording a vocal from scratch, generally, he just sings it.

People want to know why, and even Toby is not exactly sure why. It might be that it's one thing to match what's already there, but the idea of fully imitating himself for an entire song just seems like too much. That's something that Mick Jagger, for example, has no problem doing — he enjoys doing that. But maybe there is something artificial about that for Bruce.

That's a really compelling thing to look at over the years: Bruce's vocal style, how it changes, how his '75 voice is different from his '78 voice, and on and on. When he goes back and just adds a line to "Hearts of Stone" in his modern vocal and it stands out like a sore thumb.

But there is one moment in your book that takes it a step further. I wrote it down: "Springsteen is hyperaware of the point of view he is singing from, imagining different voices as different people." Where did that come from? Can you expand on that at all?

I think it was one of the producers.... I think it was Brendan who said that Bruce would tell him, "Oh, I can do it as this guy, or I can do it as that guy." I think that's where that came from. It's not literally different people... but it's like a character. I can really only extrapolate based on what Brendan told me, but it's like, "I could do it in this gruff thing, or I could do it smoother...." It's that kind of thing. Different approaches.

Oh, sure. You think about all the different kinds of voices that he's had — and still has, from that full chest voice to falsettos. But just the idea that he would even say, "I can sing it as this guy, or I can sing it as that guy"... that's pretty fascinating.

Totally. And it makes sense when you listen — he's taking on different angles, depending on the subject matter and the song.

Someone else I'm really glad you talked to is [pedal steel guitar player] Marty Rifkin. So many Springsteen books are so top-heavy — or bottom-heavy — in terms of going deep on everything from '73 to '84, and then the rest is kind of a footnote. Even Bruce's own memoir is much heavier on the early years. So it's lot of the later stuff we don't know as much about. Outtakes, whatever, the last 20 or even 30 years are shrouded in a little bit more mystery. So to have your book power all the way through and give the later stuff as much attention, that was a breath of fresh air.

I really enjoyed that, and it was a little bit more of an open field, in that every detail hasn't already been covered. I'm not sure everyone has ever talked to Marty Rifkin about The Ghost of Tom Joad, or talked to Soozie Tyrell about recording Tom Joad, and everything that follows. Or talked to Gary Mallaber, who played drums on that album.

That was fun, and fascinating — especially because I think the title track of Tom Joad is one of Bruce's greatest recordings, and such an underrated one. A lot of people don't know this: it's the only Bruce album that audiophiles, crazy-serious stereo people, would use to test a $100,000 stereo. It's his only audiophile album, with this crazy 3-D sound to it. You can really hear the room. If you ever hear it on an amazing stereo or amazing headphones, it's just really good sound.

And the funny thing is, Toby told me it could have sounded even better, but Bruce chose the kind of digital that sounded slightly shittier! It's always about getting away from the best-sounding, cleanest thing. I was like, give me a break! It was a higher-res digital that they could have... well, I forget the exact details. But there was a better-sounding version, and they let Bruce choose. And Bruce, of course, chose the objectively worst-sounding version, because that's just how he is. But even he could not mess with the sound enough — it's still an audiophile album.

Marty was fascinating to talk to. He told me that the thing he does on steel guitar on "Tom Joad" — that ghostly thing where he's not playing country licks, he's just adding atmosphere — he says that to this day producers will hire him and be like, "Do that 'Joad' thing."

I really enjoyed talking about that album because it was another one that was made in the moment. You can hear the room, you can hear them playing as a band, and it was in this room where Bruce would light candles....

Yeah, the idea that there were "daylight songs" and "daylight sessions" — that's incredible. You do the daylight sessions, and then the sun goes down, the candles come out...

Right? The daylight songs are the still-unheard "country album" — songs that were with that band that were not Joad songs, that they recorded before the sun went down. "Tiger Rose" would be a missing song from that. "Long Time Comin'" was apparently a daylight song. Then the sun would go down, the candles get lit up, and suddenly we're in spooky Joad territory.

Soozie had great memories of Joad; everyone had great memories of it. It sounded like it was a really, really special experience to be there. And I love that Marty Rifkin, within months, recorded both Wildflowers and The Ghost of Tom Joad.

But I bet Tom Petty didn't make peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for the band.

That's right! Bruce did that for the backup singers on Human Touch, too. Apparently, that was his move [laughs].

What about Gary Mallaber?

Gary Mallaber, who played on really classic Van Morrison stuff, played "Tom Joad" with just brushes. You know, there are so many great drum performances on Bruce records, most of them obviously by Max Weinberg. Almost all of them by Max Weinberg. But there are two standout, non-Max drum performances I'm thinking of, and one is Gary Mallaber on "Ghost of Tom Joad." He plays this thing with brushes that is just so incredible on that song — again, this goes back to listening to it on headphones or a great stereo. Gary talked to me about playing that.

And then the other one would be Jeff Porcaro on "Human Touch," who just absolutely kills it on that song. You have to tune your ears to really hear it, but it's absolutely sick. There's a guy on YouTube who does a drum play-along to "Human Touch." The guy is really good, and it's the closest you will come to seeing what that performance looked like. You watch what this guy is doing, and you're like, "Oh my god, Jeff Porcaro was insanely killing it on that song!"

Getty Images / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

Speaking of Max Weinberg, he and Roy [Bittan]were obviously invaluable for the book, with decades of observations. Roy adds interesting notes all the way through, but it's particularly interesting to get his take on the Human Touch period. I'm not sure I was aware that there was actually, literally, a "no piano allowed" restriction on Human Touch.

Pretty wild, right? I'm not sure how widely known that might have been, but I was really struck by how for-real it was. Of course, barring "Roll of the Dice," which was written before they could make any rules.

I also loved Roy telling me that he had written "Roll of the Dice," and "Trouble in Paradise," and I guess what became "Real World," thinking of Don Henley! [laughs] You can hear it, though. Especially "Trouble in Paradise" — as I say in the book, you can really hear Don Henley singing on that.

Oh, absolutely. I could hear it in my head as I read that. I also appreciated the fact that Roy's recollection and Max's recollection of recording "Born in the U.S.A." are so wildly different. Even though there's one objective truth somewhere, that's just how memory works. You told me about that when we first talked, but it was fun to read.

And there is so much room for "Bruce-ology" scholarship here, if anyone ever gets to do what people have been allowed to do with Dylan, to listen to all of the takes of songs. Ron apparently has access to all of that. They've digitized the archives in what seems like a really deep way. So I think the only person people on earth who could do that would be Ron, his engineer, and Bruce — at the moment.

At the moment.

But maybe someday. The the only way to solve this would be to go through all the takes of "Born in the U.S.A." And honestly, the Rashomon quality goes even deeper, because the version that Bruce has told, which is in the Marsh book, is that he said, "Hey, Roy, get this riff," and basically hummed it to him. But that's not how Roy remembers it.

And Max remembers an entirely different version: in his memory, they had a country trio version, with a country beat. And then Bruce started strumming a rhythm that reminded Max of "Street Fighting Man," and Max started playing along, and everyone came in, and that's the version where Bruce goes, "Just keep playing this riff over and over again" and kind of arranged it.

They're not disputing each other over this, Max and Roy — it's not like they're fighting each other. They think it's funny. They are both aware that they have different memories. So again, we'll never know unless and until we hear all the takes. If there is indeed a country trio version of "Born in the U.S.A.," I sure would like to hear it.

There are only a few moments throughout the book where you make judgements about the songs. Most of the time you're pretty objective. But there are a few times when you say that a song is a "minor" one, things like that. How much did you have to consider the degree to which you wanted your own opinions to be part of the story you're telling?

I think it can be annoying if you are reading a book like this and it's highly opinionated — if you're dismissing entire album. And I'm not, by trade, a rock critic. I've written some rock criticism, but very little. I think I'm semi-infamous among certain Bruce fans for writing a semi-rave of Working on a Dream. [Laughs] Which reflected my honest feelings at the time....

You admitted that you might have been "overenthusiastic."

Yeah, I say in the book I definitely may have been overenthusiastic. But I know what I was responding to: I was excited about the idea of Bruce going to this expansive, beautiful, pop thing. I may not have stopped to consider the extent to which it worked or not [laughs]. I still will defend some of it. But anyway, I'm not very good as a rock critic, for the most part. That's not exactly what I do. As a feature writer, which is mostly what I do, you tend to push your opinions back a little bit, and you're more about telling stories.

That said, there are times when you just have an opinion. I do have Bruce opinions, and there are times when it comes out. It was always like, if all else fails, maybe I will have something interesting to say on that level.

Like "Cynthia."

That is not a good song, I'm sorry [laughs]. It's not a bad song — I know Steve loves it for some reason — but I really think it's a throwaway. And what was fun was to see someone like Chuck totally agree with me.

What was his line? Something like, "We call these rockers, but they are not rocking."

Yes. And that's what's fun — again, connecting dots — in the Marsh book, with Chuck, there's a part where they talk about recording all summer without getting anywhere. But what we didn't know at the time was which songs they were recording. And now we know that it was stuff like "Cynthia."

And so the story your Born in the U.S.A. chapter tells is about how it was a matter of convincing him to go back to the earlier material that he had set aside.

Right. Again, the Born in the U.S.A. story is just extraordinary. Extraordinary not only that they recorded so much, as we were saying before, but that he had so much of the best stuff early on! But because of his instincts to just bludgeon away, to work so, so, so hard, he had already worked his way past the best stuff. It was deep in the past.

Of course, he was never not going to release the title track. As Max says, they knew what they had. I love that story of Bruce driving over to Max's house after being up late recording that, and he played it for him on the boombox and said, "Look what we just did."

Getty Images / from Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

Okay, we've talked a lot about people that you interviewed specifically for the book. But I also want to touch on the stash of Bruce interviews you had to draw on, the five that you'd already done yourself. What stands out? As helpful with the book, or just as particularly memorable?

Little moments are very memorable. I don't think I even mention this in the book, but there was a moment in my interview with Bruce at the Buffalo show in 2009, where they were going to play Greetings. This was for a retrospective issue of Rolling Stone that came out in 2010, and Bruce was going to be one of our "Artists of the Decade." So we were talking about his decade of work — which, obviously, turned out to be very useful for the book.

He was about to play Greetings that night in Buffalo. A very, very historic show, obviously. And he had also just played The River for the first time at Madison Square Garden. During that performance, it was either "Crush on You" or "I'm a Rocker" — either way, it was one of those throwaway songs, that Bruce himself had said he didn't think much of — but it had this this amazing moment at the Garden where he threw his guitar over his back and got really, really into it, and it became incredible.

So at the end of interview, we were just kind of talking. And I said, "Man," you know, "'Crush on You,' that was so amazing the other night, that song really came alive!" And he was very much aware of it himself, so he became very enthusiastic, and he was like, "Yeah!"

And then I said — I actually said — "Well, maybe it's 'The Angel''s night tonight!"

[Laughs] I must say, he was not amused at all.

"You took it one step too far, Hiatt!"

Seriously, it becomes, like, "Who the hell are you?" Which… fair enough. Don't get too comfortable. So that stands out for sure.

Thinking of the interviews you did, there's a line from one that's really powerful. In 2010 he told you that when he is "on stage with all those people out there, the abyss is under my heels, and I always feel it back there." The abyss. That's heavy.

Yeah, that was from my interview for Darkness. I used that in the Nebraska chapter. We were really skirting, really edging towards a discussion of depression without coming out and saying it; this was before he had gotten explicit about it. Although in Glory Days, Dave Marsh used the word depression — so again, these things are often hiding in plain sight.

And you describe "Reason to Believe" as "a bulletin from the abyss." I dug your take on that song — no equivocation. It's one that isn't quite as misunderstood as "Born in the U.S.A," but it can be. It's a far darker song than a lot of people seem to think.

Oh, my god, yeah. I hesitate to go into superlatives like "one of the darkest songs ever written," but it's pretty dark, man. It's one of those pieces of art you don't want to stare at too long. It's a little bit of a cry for help. It really is.

You mined the Christic shows nicely for the Nebraska material, as well as the '90s songs. You mentioned Christic last time we talked, and I appreciated how much you went back to those for the book. Because those are really just crucial, crucial stories and performances.

There have been a few times when he really offered a "key to the locker." What he said during those shows, that certainly is one of them. The DoubleTake shows were other ones where he said things that he's never said before or since. Again, more data to draw on.

Putting it all together, the text goes almost surprisingly "deep" for a coffee table book, which I think of typically as a general audience thing. Compared with some other Springsteen books, this feels less like something for a mass audience. I won't say that too loudly, but as a hardcore fan, I feel like, "Oh, this book is for me." How did you think about your intended readership?

I would like to think it does both. I tried to treat it like there may be readers who don't already know any of these stories, and I do think that it's accessible for someone who just kind of likes Bruce and would like to learn more. I definitely had to balance that. It can't just be for the hardest of hardcore fans who only want the absolutely freshest little morsels of the most trivial but new information.

There were little bits that would only be of interest to hardcore fans. For example, Chuck Plotkin told me that there were sessions before the Brendan O'Brien sessions — in the spring of 2001, I believe — as I say in the book, they were more like demo sessions with the original production team. They recorded a bunch of stuff, but they weren't really recording for an album; they were just kind of seeing what they had. One of the things they recorded was "My City of Ruins." And Chuck liked that version better — it was slower, I think.

That's the kind of thing that's truly for the hardcore fans. There's plenty of candy for the hardcore fans, but I didn't want to go insane with it, because this had to be a book for everyone.

It's not all inside baseball. And, in fact, the way you go about it, there's a clear narrative throughout the book. It's the story of Bruce and the band, told via the songbook. And by doing it chronologically, it's a story that you can put up against something like his memoir. Bruce talked about Tracks as an alternate roadmap for his career. And in a way, this is an alternate roadmap for his biography — through his work.

You certainly get a narrative. Hopefully it's a companion to a book like... well, the book of your choice, whether Born to Run or Peter Carlin or Dave Marsh. I think, and I hope, that it works alongside them.

Order Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs,

SIGNED BY THE AUTHOR

Rolling Stone excerpt: "How Bruce Springsteen wrote and recorded 'Born in the U.S.A.'

Rolling Stone excerpt: "How Bruce Springsteen created 'Badlands'"

Rolling Stone excerpt: "How Bruce Springsteen created 'Thunder Road'"

|