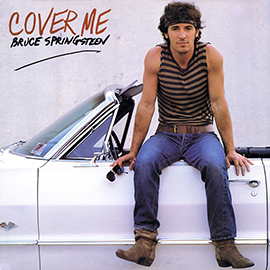

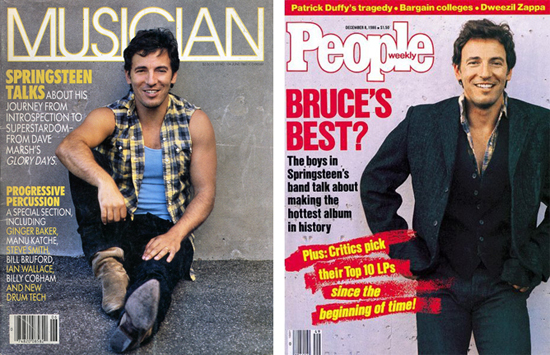

Whether they know it or not, every Bruce Springsteen fan is familiar with the photography of the late David Gahr. The very first ready-for-his-close-up portrait of Springsteen on an album cover came courtesy of Gahr, on the cover of 1973's The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. A decade later and a beard lighter, Gahr captured Bruce again for the picture sleeve of the "Cover Me" single. After the release of Live/1975-'85, another Gahr shot graced the cover of Musician magazine. What's lesser known, though, is that between 1973 and 1986, Gahr shot Springsteen — onstage and off, with and without the E Street Band — on no less than 25 occasions.

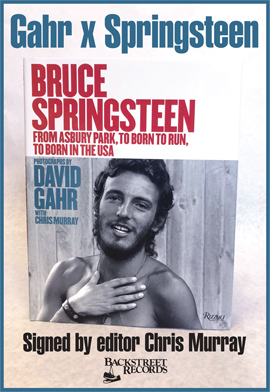

A new book from Rizzoli, Bruce Springsteen: From Asbury Park, to Born to Run, to Born in the USA, finally reveals the breadth of Gahr's work with Springsteen, in session after session documenting his rise to superstardom. Govinda Gallery founder Chris Murray was tapped by the Estate of David Gahr to put the book together, making selections from thousands of black and white negatives and color slides for a definitive collection.

As curator and editor, Murray is a true pioneer in the world of rock 'n' roll photography, championing through his Washington DC gallery the work of Al Wertheimer, Annie Leibovitz, and countless other fine-art photographers in the world of music. His nineteen books include four collections of Wertheimer's Elvis Presley photographs, including Elvis at 21: New York to Memphis.

The first collection of Gahr's work in 50 years, From Asbury Park, to Born to Run, to Born in the USA is Murray's second Springsteen book — in the early 2000s, he curated the first show of Frank Stefanko's Springsteen photographs at Govinda and edited the accompanying Days of Hope and Dreams. It's also his first work (with more to come) with the David Gahr Archives. "David Gahr's photos of Bruce — that we now have a book of them, it's such a celebration for me," he tells Backstreets.

Chris Murray and Backstreets editor Christopher Phillips recently spoke at length about the book, the late photographer, and the magic that happens "when you bring together the great photo and the great musical artist."

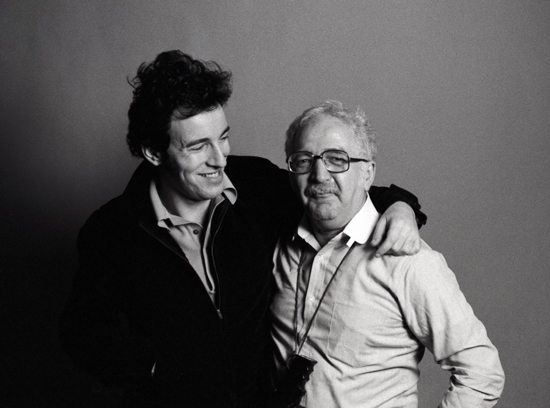

The Power Station, NYC, 1980 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

Backstreets: One of the interesting things about David Gahr is that, out of all the famous photographers of Springsteen over the decades — Eric Meola, Lynn Goldsmith, Annie Leibovitz, Frank Stefanko, Danny Clinch, the list goes on — Gahr's may be the ones that people don't know that they know.

Backstreets: One of the interesting things about David Gahr is that, out of all the famous photographers of Springsteen over the decades — Eric Meola, Lynn Goldsmith, Annie Leibovitz, Frank Stefanko, Danny Clinch, the list goes on — Gahr's may be the ones that people don't know that they know.

Chris Murray: Exactly. There are those 23 million Miles Davis stamps or 60 million Janis Joplin stamps [printed by the United States Post Office using Gahr's photographs], not to mention to mention the cover of Bruce's second album. But he's still not a household name, I couldn't agree with you more.

But my friend Gered Mankowitz in London, who took famous photos of the Stones and Jimi Hendrix, he said, "We knew of him as the godfather of music photography." You mentioned Annie — and I remember Annie and many others, like Dick Waterman, saying, "Oh, David Gahr was the best."

Let's talk first about who you are, and what you do. I had the pleasure of living near Govinda Gallery for a number of years in DC — we met there probably almost 20 years ago now. But for people who don't know your history, maybe you can fill that in a bit.

Well, that little list of photographers you mentioned — do you know I had the first exhibit for every one of them? I had Danny Clinch's very first show; I did Annie Leibovitz's first show, Lynn Goldsmith's first show. Frankie, of course.

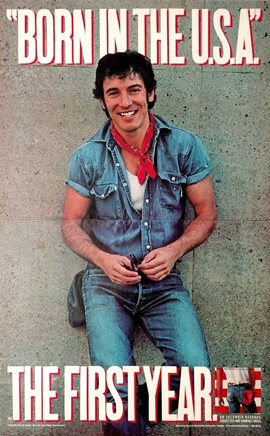

Annie Leibovitz's first show in 1984 became very important to me. She had just left Rolling Stone, and it was her first book. That classic Born in the U.S.A. photo of Bruce — you know, the cap in his back pocket — was in that show. It's probably the first photo of Bruce I ever showed, actually. But it wasn't a rock 'n' roll show. Along with Bruce and Bob Dylan and Pete Townshend — you know, with the bloody hand — we also had Muhammad Ali and Norman Mailer and Arnold Schwarzenegger and Harrison Ford.

So this was before Govinda became what it became, in terms of music photography.

Right. But in that show was a photo of John and Yoko. I love The Beatles like Bruce loves The Beatles. And the famous one where John is naked, holding onto her? Annie's in the gallery, alone with me, installing that for the exhibit. Can you imagine, just the two of us? I must have had an assistant there, but no PR teams, no videographers, no assistants, just Annie. We're putting this show up, which was a great experience, and I said to her, "Annie, I love The Beatles. I'm going to buy my first photo of yours."

It could've been anything. I could've bought her Muhammad Ali. But I said, "I'm going to get this one of John and Yoko." And she turned to me and said, "You know, Chris, John was murdered the day I took that photo." And at that time, in '84, John had only been killed a few years earlier, when people saw the photo on the cover of Rolling Stone, and I think few people realized that photo was taken the day John was killed. I hadn't.

I literally had an epiphany that very moment. I'm not kidding. I didn't share it with Annie, but I said, "Not only is this a good photo, it's an important photo." And I decided, since I've always loved music and rock 'n' roll music, it hit me: There must be other great photos like this out there, that are transforming, that are significant. And I said, "I'm gonna find them." And so that's what I did.

I think it's important to point out that you were a trailblazer in that sense. I mean, this was pre-Morrison Hotel Gallery or anything else.

Way before Morrison — a decade or more before. They're a really good team there. They get all sorts of things, and they do a good job. But Govinda's selection, our curatorial point of view, was unique. We got to the heart of great photography.

The reason it succeeded so well is because I applied the same criteria to the rock material as I did to the photos I shared before that, which ranged from 19th century British photographs to fashion photos. Photos from Nepal in the '30s to Doc Edgerton, who invented the strobe light, to Edward Sheriff Curtis, who did the famous North American Indian series back in the late 1800s. The reason it succeeded is because I applied the same criteria to Mick Rock's photos of David Bowie, Al Wertheimer's of Elvis, Danny Kramer's photos of Dylan, Baron Wolman's photos of the San Francisco scene… it goes on and on. Kate Simon's photos of Bob Marley. Whatever it was, I wanted the best. I wanted it to be as if I were working on a show of Ansel Adams or Richard Avedon.

So I went on a quest to find the finest photos of musical artists out there. Al Wertheimer is the number one of all of them. And it went from Elvis to Jay-Z, frankly, from Wertheimer's Elvis to Jonathon Mannion's wonderful photos of Jay-Z. And in between was Mark Seliger and Danny Clinch and Kate Simon and all these great photographers. Herbie Greene, who did the San Francisco scene along with Baron Wolman, and of course, Jim Marshall. Ken Regan's photos, I discovered them — he was the photographer Dylan hired to go on [the] Rolling Thunder [Revue].

So Govinda Gallery championed significant photographs documenting rock 'n' roll, and people came in droves. It was fun for me, discovering these artists and finding photos that weren't necessarily the ones picked for commercial reasons. And I tell you the Annie story because that's how my interest started.

That was the turning point, to get to what you've been doing ever since?

It's a long way of telling you it brought me right to David Gahr.

That same aesthetic is here in this David Gahr book.

I try to have the same approach with my books. I want them to be about photography — about David Gahr as a photographer, with the emphasis on a great image. When I was doing the Elvis books, I'd say, "I want to treat this work like we have a book of Richard Avedon's photos. That's the approach." By respecting this as great photography, you respect the subject, too. When you bring together the great photo and the great musical artist, there's really a magic there.

David's body of work is extraordinary. For me it was like finding the ark in Raiders of the Lost Ark or something. He really is one of the greatest photographers we have of American music. If you look at The New York Times obit, David Gahr had a Master's degree in Economics, and he was hired by New Republic magazine to write about economics in Washington. So this guy was quite clever and bright. But he didn't want to do that because he loved music so much — and he loved it so much, he started taking pictures.

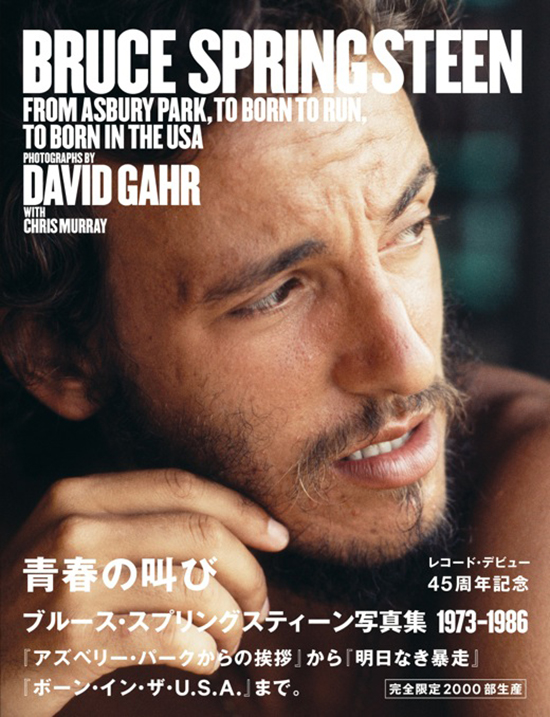

A nearby frame from Gahr's The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle session is the cover of the Japanese edition

Back in '73, when Columbia hired him to shoot the cover of Wild and Innocent, I know he'd shot Dylan… was folk music primarily his thing?

Back in '73, when Columbia hired him to shoot the cover of Wild and Innocent, I know he'd shot Dylan… was folk music primarily his thing?

Exactly. When he died in 2008, he was 85, and so you can imagine that was the prime time for him, musically speaking — folk music. The folk revival was on, and David would go everywhere to photograph the folk movement: The Newport Folk Festival, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Dylan, the Chambers Brothers, Donovan, Muddy Waters, Johnny Cash. I've been looking lately at all of his photos from the three Newport Festivals he went to, 1963, '64, and '65. For instance, with Dylan, you can see him in '63 just as a folkie in David's photographs; in '64, he's transforming and he's with Joan Baez. And then you get to '65, he's with The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and he's about to blow the world's mind at that same show when he goes electric.

So sure enough, his book The Face of Folk Music is the greatest publication on that sort of music — an incredible document of folk music. And that book, coincidentally, was published 50 years ago this year. It was the only book David Gahr ever did during his lifetime.

It was a really fertile time for traditional American music and songwriters. And that's the music that Woody Guthrie inspired, and that's what inspired Bruce Springsteen, you know? There's a direct line between Bruce and that tradition. There's a line there between David and Bruce, too, because Bruce loved that music and here Gahr, the next thing you know, he's photographing Bruce Springsteen in 1973. I like that connection.

Bruce Springsteen and David Gahr, 1979 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

One thing your book documents underneath it all is how much David Gahr must have really taken to Bruce, to follow up the initial shoot with 25 sessions.

It's crazy, I was amazed at how many different sessions. So yes, clearly, there was an affinity there — David clearly, very quickly, took to Springsteen and his music.

When I get involved in these books like these, I get so absorbed in the photographers and the subjects. I looked at 7,000 images in this case, more or less. There are contact sheets with multiple similar images from a concert, and I look at every single one, just to make sure I don't miss a magic photo. And sure enough, I found a lot of them. One is that photo of Bruce and David Gahr together, where David's got this delightful grin. And mind you, David would've been about 55 or 60 then — enough to be a father figure. Not that he was a father figure to Bruce, I'm not saying that, but he was a little older and he'd been around the block. And there's Bruce with his arm around him, and it's such a satisfied grin.

From what I understand from Joel Siegel, a great blues guy who's now running the Gahr Estate, Gahr was a character. I get the impression he was a real piece of work. He didn't suffer fools lightly, and he could really throw out some zingers. But you can tell he's so loving Bruce in that picture, even if he was cracking a joke or something. Bruce has a great smile, too, and the way he's looking down at David, I see almost a father-son connection. So it speaks to what you were saying — they developed a bond.

And that's the essence. That's why there was a golden age of music photography from, let's say, 1956 with Al Wertheimer and his photos of Elvis, up to the turn of the century. Photographers could be with the musicians, hanging out with them. They could know them. And for them to develop this relationship over a period of all those years, 25 shoots, Bruce and Jon Landau and David must have had a great affinity for each other. You can see it in the photos.

Both cover images from Gahr's last session with Springsteen, outside Giants Stadium in 1986

You see that developing relationship unfold in the book: David shoots for the record cover, then there are some live photos, and then all of a sudden, he's at a barbeque outside with Bruce and his girlfriend. And it's suddenly a much more intimate view.

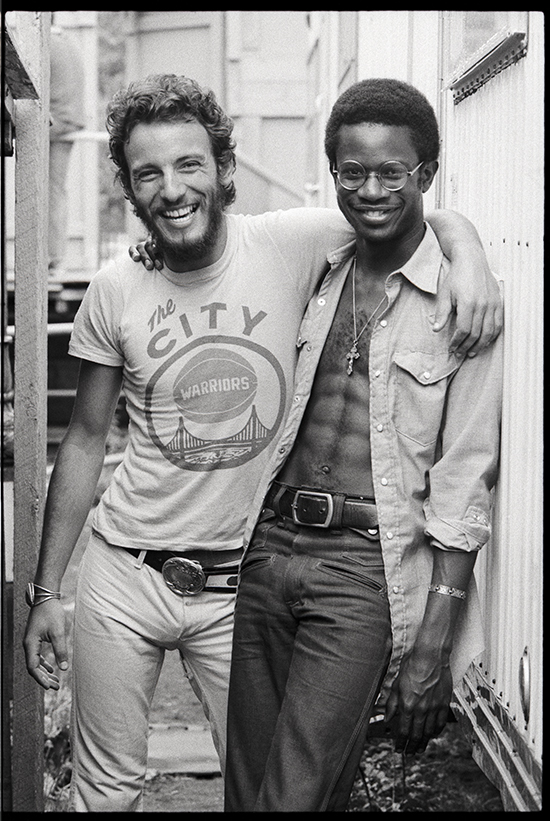

He must have developed a relationship, a certain amount of trust. They wanted David there, and David wanted to be there. It was definitely mutual. I love that section where Bruce is meeting Jon Landau there, they're shaking hands. And if I'm not mistaken, they weren't working together yet, exactly, is that right?

Well, you'd have to know exactly when it was in '75. They were already friendly before Jon came in to advise on Born to Run, and then became the co-producer, and then on from there. But he wasn't manager yet. So it's certainly a very early time in that relationship.

That double page spread, two photos where Bruce and Jon are reaching out to each other shaking hands, to me it's like Bridge Over Troubled Water or something. You can see that they're friendly, but…

But it's a handshake, not a hug, right? There's something formal to it. And then, to have all the foliage in the background, they're just beautiful images. Bruce and Jon in the garden.

That handshake meant a lot, I have a feeling. I think a lot of people might get a kick out of that.

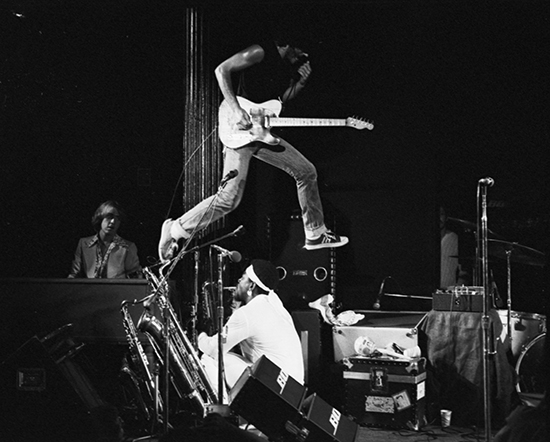

The Bottom Line, New York, NY, August 14, 1975 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

So many of the David Gahr shots I'm familiar with from over the years have been offstage. So, it was a revelation to see how much concert photography he shot. And very big nights, too, you know? Like, the Bottom Line shows.

Such a legend, that series of shows. I didn't get to see it, but of course I heard about it. And don't you love that photo? Well, there are a few. I love that photo of the Bottom Line marquee, that shows Bruce Springsteen but it also shows who's coming up….

With Nils Lofgren listed there, too?

Right! I love that. When I had the loupe on the contact sheet looking at these photos, and all of a sudden I saw that, I had a big grin. Which is not a pun on his band! But I grinned when I looked at it because, you know, Nils is a local boy. I live in Washington and Nils is from here, and so, he's always been a popular character here. So it was terrific to see that David had shot that marquee. And then, that David had the sense to take a shot of the line! It was all the way down the block.

I love that you made it a spread — such a nice, big photograph of that beautiful vintage moment in New York City. And then, of course, from the show itself, there's one that's amazing…

Where Bruce is jumping off the amp?

Yes! He's airborne, it's crazy!

What is that? I showed it to my son David, who's a big time music fan. He grew up on punk rock, and he loved it. And let's face it — Bruce was a punk rocker, too [laughs]. He's got that cool Telecaster, and he's got those sneakers and the cuffs rolled up.… It's remarkable. It's like he's walking on water, like he's walking on air there. My son wanted to know how he landed!

There's relatively little visual evidence from those Bottom Line shows, and yet so much legend surrounding them. Just to see that one shot kind of explains it.

You were saying what a revelation it is to see all this live work from David. As I said, [at Govinda] we were championing music photography. There's been some live work we'd feature, but we focused mainly on things like Al Wertheimer's images in Elvis at 21. Most of it was these behind-the-stages, candid, fly-on-the-wall stuff. Because a lot of stage photography can look the same. Not with Al's stuff… but too many times it's just a band on the stage. And maybe people love the band and they identify with it, but photographically speaking, there has to be something outstanding to catch my eye in that regard, documenting an important moment.

Like the chapter in the book where Bruce plays a magazine party, which comes next — it's 1976, and it's the 10th anniversary party for Crawdaddy. When I saw those photos, looking in my loupe, and I had never seen them before… nobody's ever seen them before! You know, 90 percent of the photos in this book have never been seen. But when I saw those, it was like… this is a treasure! I just thought, "Oh, my God, this guy is the greatest rocker in the world!" He's got so much soul, so much vitality and expression, and the band is so young. And the audience — it's so small!

And the stage is the size of a postage stamp. It's the smallest stage I've ever seen them on.

Yeah, the stage is about the height of a dining room table. There's one of Bruce there where he's walking across the stage — he looks just like Otis Redding or James Brown or any of those great R&B soul guys who would strut. The crowd's going crazy, and he's into it… There's another one where Bruce is center stage, it's a double spread. He's not using the guitar, but the band's playing, and his hands are up in the air. There's light on his hands and face, and it looks like a revival. Of course, it was a revival. You can see everybody in that audience smiling. And this is early on for Bruce, relatively speaking; he wasn't the Bruce he's known as today. Those photos were a revelation for me, because they were so rocking. Those 1984 photos from Baton Rouge are wonderful performance shots, too.

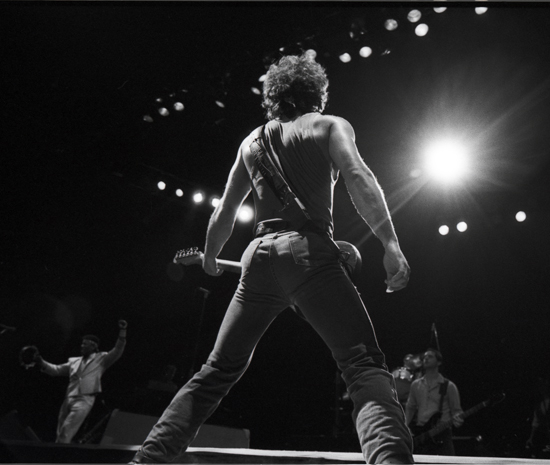

Baton Rouge, LA, December 2, 1984 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

Yeah, that Baton Rouge section really captures the rock 'n' roll icon that Bruce became at that time. Like that shot from behind, where he's got his arms tensed at his sides, looking up into the lights….

That's an amazing photo. It's so immediate and strong. And you really feel the energy that fills Bruce up when he's performing. It's a good example of why I had to go through every single image, because I didn't want to miss the one — like that shot you just cited, there was only one photo of that moment. There weren't a lot. There was one.

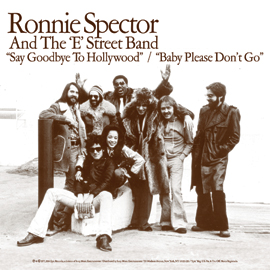

And then, you know, I love Ronnie Spector. To see her on stage with Bruce and the band... and there's that shot of her with Clarence here that David took, it's unreal. I love that Bruce was always a supporter of some of the legends who he obviously loved, like Ronnie, like Gary U.S. Bonds.

And then, you know, I love Ronnie Spector. To see her on stage with Bruce and the band... and there's that shot of her with Clarence here that David took, it's unreal. I love that Bruce was always a supporter of some of the legends who he obviously loved, like Ronnie, like Gary U.S. Bonds.

So it affected me deeply, to see these great, unpublished stage shots of this great entertainer. Seeing how he had so much passion for what he was doing at the Crawdaddy party — it looks like his whole being was into these shows. And of course, he became famous for that.

Right, you really do see him become famous over the course of the book. From this skinny young beach bum with a scruffy beard to king of the world.

From artist to icon, as I say in my essay at the beginning — it's really the arc of Bruce. You see him start as this young musical artist on the Jersey Shore, and the last shoot was in '86 outside Giants Stadium.

I love that picture in the beginning of the book, that double-page spread on the lawn in '86, Gahr again taking a portrait of the whole band. When he first shot them in '73 or '74, you see the band lining up like any rock 'n' roll band would at first, when somebody wants to take a picture. But in '86 outside Giants Stadium, they're all sitting, and he wanted to get them close together. They're all smiling and kicked back and relaxed. So you can see how it went from the beginning to this point, where they've been playing together for over a dozen years and were a unit. You get to see how the band grew and transformed.

Well, sure — you've got both piano players here, David Sancious and Roy Bittan, and different drummers too.

That first drummer, what a character, huh? He's a wild man — what's his name again?

Mad Dog — Vini "Mad Dog" Lopez.

He looks like it! [laughs] I knew guys like that. It was a great pleasure for me to get to know The E Street Band in its various formations throughout this process, and in that way the book also shows the story of the band.

Springsteen and Sancious in Central Park, 1973 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

I think I may have mentioned to you that shots of the horns onstage with Bruce in the '70s are pretty rare. It was a regular thing in '76, '77, but they don't show up in many photographs — I'm always looking for them.

I remember finding those. As I progressed, all of a sudden — oh, gee, now there's a horn section in there! Musically, things have evolved. David tended to get a lot of the band, but often the light was on Bruce. So sometimes you wouldn't necessarily see the horns, but I came across some good ones and they look terrific.

And then you get to the 1980 session that David photographed at The Power Station. In that chapter of the book, right after the first two great photos of Bruce at the control board, I found in David's archive these individual portraits of each of the E Street Band members while they were recording — I love those pictures.

You've got the full band on the rooftop in black and white, which we're familiar with.…

Is that one known?

Yeah, or shots very much like it — on the inner sleeves of The River. I'd have to check, but if it's not that very frame, a similar frame. They're being serious. But I was going to say, the thing we haven't seen is the next shot — all of a sudden they're all jumping up and being goofy.

I love it.

That's one of the fun things about the book, seeing shots that are familiar juxtaposed with shots that aren't. There are a lot of moments in here that people will be reminded of: "Oh, that's right, the 'Cover Me' shoot…," or some other Born in the U.S.A. promotional stuff, and then you see a photo you've never seen. Or one of those off-stage shots from '86 that was used as the cover of Musician magazine, followed by a frame that we've never seen before. A lot of those juxtapositions.

That's one of the fun things about the book, seeing shots that are familiar juxtaposed with shots that aren't. There are a lot of moments in here that people will be reminded of: "Oh, that's right, the 'Cover Me' shoot…," or some other Born in the U.S.A. promotional stuff, and then you see a photo you've never seen. Or one of those off-stage shots from '86 that was used as the cover of Musician magazine, followed by a frame that we've never seen before. A lot of those juxtapositions.

Right. Another one I love is the spread where Bruce is standing with the band, and then on the next page he's standing with a bunch of girls. I love that shot with the girls!

It took me a second to find him in that shot!

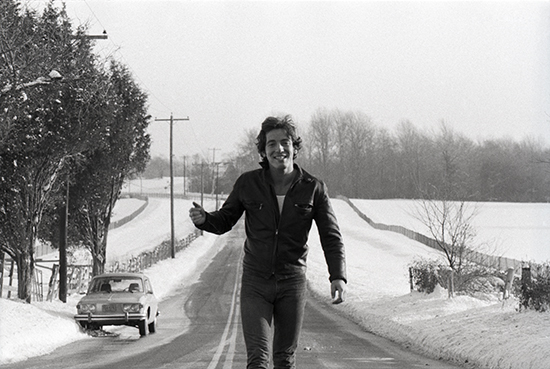

Yeah, I love that photo. Because you're so used to seeing him with the band with his "team." But that photo with those girls was so cute. And it demonstrates how much humor there is in this work too. Another one — Gahr must have had an assignment to get shots of Bruce for promotional purposes, and then he just took these wonderful shots walking down the road, as if he's hitchhiking.

He wasn't really hitchhiking — I don't think [laughs]. I think they were walking together, David took a shot of Bruce, and Bruce — well, we've all been with a friend walking down a road and you stick your thumb out jokingly. We've all done that.

New Jersey, 1979 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

Imagining you going through 7,000 frames to find these, what was the process like of making these selections?

Well, first of all, as an archivist and a photo editor, to have the original source material at my disposal was amazing. To be able to look at the vintage contact sheets that David Gahr made — he would take these photos and then print a contact sheet of them, and they would have David's own markings where he'd mark photos that he particularly liked by outlining them with a grease pencil. You know, how they used to do it [laughs]. Of course, this work is all pre-digital.

And so, to have that sort of source material to look at was an extraordinary, creative trust. It was like looking through David Gahr's eyes. Because as I started looking at these, shoot after shoot, things started being revealed to me in a way as my eye was adjusting to David's eye.

The first thing I do is to go through the original material and get a feeling for this 13-year relationship between this musical artist and this visual artist. Just to get the flow. And then I go back and literally look at every single frame — it was like an archaeological dig. And you'd be sifting the sediment and then all of a sudden—boom, look at this jewel! So, that's what I would do.

I noticed you thanked Bobby Ward in the book, the David Gahr archivist, and I was curious — was David himself was very organized? Or did Bobby do a lot of the organizing before it came to you?

Both. David was very organized, and he numbered all his contact sheets, kept them in files. He was very organized. But when David passed away, they wanted to move the archive into a temperature-controlled facility and to preserve them in good form for whatever purposes would come their way. Bobby Ward did a terrific job organizing the material, and he gave me what I thought of as a script. Because he broke down all 25 shoots — where they were, and what year they were — so I would know the chronology. That was a great roadmap for me. So I was able to say, "Okay, here we go — 1973. The beach towns in New Jersey," and just start in that way. And I treated it chronologically, because there is a story. Rather than taking photos from '73 and then mixing them with '77 and then going to '86 and then going to '74.… no. I'm telling a story here, and each of these years is like a chapter of that story.

Sometimes I'd have Bruce's music on while I was doing it. That's fun, I'd get excited. Then other times, you'd want it to be quiet as you're looking at everything. But handling these photos was a real honor and a real pleasure, especially the relationship with David Gahr. The story of Bruce was unfolding in front of me, but internally, David Gahr was really unfolding as well, and his approach to photography. And so now I have such an incredible appreciation and admiration and respect for what he did.

It's quite an opportunity you were given.

I have to give props to Joel Siegel, of the David Gahr Estate, who really empowered me. But when it comes to the development of the book, I really owe it to Peter Guralnick, who's my literary hero. I think Guralnick is probably the best music writer out there. I mean, he wrote The Last Train to Memphis, which was a great source for my books on Al Wertheimer's Elvis photos; he wrote the great book on soul music, which I'm sure Bruce knows, Sweet Soul Music. His latest one is a mind-boggling book about Sam Phillips. He's America's greatest music biographer. I'm making that statement boldly and with confidence.

Well, I don't know that many would disagree. And so Peter is the one who connected you with this in the first place?

Yes. The short story is, the David Gahr Estate contacted Peter Guralnick and said that they wanted to make some books, and Peter just said, "Call Chris Murray." So they did. Even though I didn't know David, I knew of David, because I had heard other photographers talk about him.

So you'd never met him?

Here's the only contact with him I had: I did a big punk rock show, called The Cool and The Crazy. It was an amazing show with all these photographers there: Bob Gruen, Anton Corbijn, everybody who had been photographing punk rock. In the show was a photo of David Johansen, not looking like a New York Doll… actually looking kind of like Bruce in portraiture, standing in front of a building, looking great. And a guy named David Gahr took that photo, who I didn't know. This was one of two shows, I'd say, out of the 250 shows we did, that I didn't organize.

I sold that photo, and I contacted David to tell him. I had a chance to speak to this guy a couple of times on the phone, and he was very happy that I made the sale, and I was getting the address where to send him a check. And that was it.

But even though I clearly didn't know David well, after speaking to him a couple of times, I got a sense of this guy's dynamic — he was a very lively fellow. And I have to tell you, even before this project came my way, I always thought to myself: there's only one person who comes to mind for me who I never got to show in the 35 years of Govinda Gallery, and it was David Gahr. And then David passed away.

This is the first book I've done with somebody who is deceased. I've always worked with the photographers themselves. I'd give anything to have David Gahr back here with me for a couple hours. I'd ask him a lot of questions. But for years I'd literally think, "Oh, I wish I could've shown David Gahr." And now I am. I'm showing it to so many people through this book. And so, for me, it's a great present.

Springsteen and Landau, 1979 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

I've already told you how much I love the shot of Bruce wearing Landau's glasses.

I love, love, love that photo. That photo is a whole story. There's so much nuance. You can tell Jon's being… he's cooperating, so to speak [laughs]. Bruce clearly took those glasses from Jon, and then — I'm speculating here, but he must have said something like, "Oh, come on, give me those." Because you see Bruce's head — you know how you are with a friend, and they're trying to grab something from you and just lean back a little, like, "No, you're not gettin' this," you know? It's a hilarious photo, but it's also a photo that shows a relationship between two people that's really intimate.

Right. It does not come off as a gimmicky photo, like, "Hey! Let's have you put on Jon's glasses!" It feels like a moment between two friends.

It must have been. I'm sure David Gahr didn't suggest that, you're right. I imagine Bruce was goofing with Jon, and David caught a great moment.

It's fun to talk to you about all the "holy shit" moments I had when I flipped through the book, whether it's that photo or the shot of Clarence and Ronnie, and to hear that you had those same feelings when you saw those photographs.

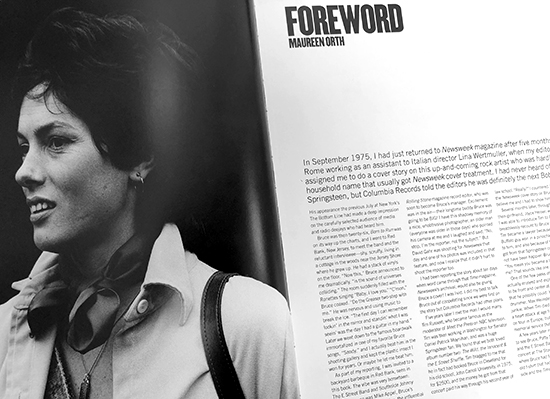

Here was another one of those moments: Maureen Orth [who wrote the famous 1975 cover story for Newsweek, "Making of a Rock Star"].

I wanted to ask you about that — she wrote the foreword, and the photo that you ran with it… did David take that too?

Yes — listen to this. I was going through the contact sheets, and all of a sudden I'm seeing these photos of this young woman, from the barbeque.

Bruce Springsteen: From Asbury Park, to Born to Run, to Born in the USA (Rizzoli)

Wait — that shot of her that's across from her foreword, that's from the barbeque with Bruce and the band?

Absolutely! There were eight photos of her, and they were all at that picnic. I said, "Why is David shooting her?" I thought there was something familiar about her, but I didn't know. And I turned over that contact sheet — it was the only one with something like this on the back, and it said, "Newsweek's Maureen Orth."

I said, "Oh, my God, Maureen!" I know Maureen, because she lives in Washington. You know her husband, Tim Russert, was a big fan — he loved Bruce — and a music photo fanatic, too. Maureen and Tim used to come to Govinda Gallery. Tim bought some of Frank Stefanko's photos, from that first exhibit we had, which I think is when we met. Maureen would also come in with her son, and they'd buy photos for Tim. Tim would come in and buy photos for Luke. It was very cute. So I got to know Maureen and Tim from their love of rock 'n' roll.

When I saw these, I said, "Holy shit — that's Maureen!" I got on the phone and called her up, and I said, "Maureen!" I told her that I'm editing this book, and I came across these photos, and this woman who I thought looked familiar… and she said, "Oh, my God!" She didn't know about the photos. Again, nobody had seen these photos! She lives nearby me, so she came down and I showed them to her. It was such a pleasure for me to have Maureen here — an eyewitness to that moment in the book. And of course she was there because she was writing the first Newsweek cover story on Bruce Springsteen.

I was curious, because looking at so many of his photos, I never saw David do that in any of them — going up to someone else who wasn't the subject. Besides Jon, to tell you the truth. He clearly liked photographing Bruce and Jon. There were a lot of photos he had with Jon; I only picked a couple of them. But yeah, something about Maureen drew his eye.

And all of a sudden, here's the perfect person to write a foreward, right?

Exactly. Maureen sat down with me to look at these, and a lightbulb went off, because I was looking for somebody else to write a little essay. We had invited Bruce, but he very graciously declined because he was so busy getting ready for the Broadway show. And the next thing you know, I see Maureen.

I really think her essay is really compelling, because that was an important time. She explains that Time magazine was doing a cover story at the same time, which was highly unusual, because Bruce, quite frankly, wasn't that famous yet. People would say, "Why is this guy on the cover of Time and Newsweek?" Save that for Winston Churchill, you know what I mean?

I loved her story of how she and Tim connected and one-upped each other, over their connection to Springsteen.

Yeah, it was something. Tim Russert loved Bruce, and not only that, but Bruce really loved Tim. When Tim died so young, I found out from Maureen that Bruce made a video eulogy, which was shown at Tim’s memorial service. But Maureen wrote the [Newsweek] story. She had a copy of it that she showed me, and of course, one of David Gahr's photos accompanies the story.

"Can you get us a ride?" Telegraph Hill, Holdmel, NJ, 1977 (©The Estate of David Gahr/Courtesy Govinda Gallery)

This is the first book you've done by a photographer who's no longer with us, and it's your second Bruce book after Frank Stefanko's Days of Hope and Dreams. I was wondering how different these two books were to put together. Working with Frank, who's a pretty lively guy in his own right, must have been a pretty different experience from this one.

I mention Frank in my acknowledgements. I also did his Patti Smith book, Patti Smith: Portrait of an Artist, which was a great pleasure, too, and I had Frank's very first exhibit at Govinda Gallery. And it was a different process.

One part of that process that I loved is Frank's stories. I would record them and transcribe them, and you could hear straight from Frank what was happening that day, hear about what he was thinking, about his home where some of those photos were taken, and about Bruce. I find out what the vibe was, and what they were doing. Frank would tell me a story about driving a car with Bruce down the highway… so I could get a real sense of the flavor firsthand. An oral history, if you will. All the other books I've done, I've done that: I record the photographer's unique stories and present them as they tell them, and it's a firsthand oral account of these situations. This is my 19th book, 12 of them on music, and every one of those books, I interviewed and quoted the photograpers.

So I didn't have that opportunity to talk to David. However, Peter Guralnick and Joel Siegel and other people would tell me about him. Peter called him "a great mensch." So I could get a sense of it. And when you have this abundant amount of material, you get a sense almost as if you were talking to David Gahr, you know?

But that's one of the big differences — it was wonderful to be able to ask Frank about Bruce, about Patti Smith, about himself. To hear firsthand from him about Bruce and about Patti and everything he saw and experienced and witnessed. I gotta tell ya, you couldn't find a nicer guy than Frankie Stefanko.

Oh, it's so true.

I want to tell you a little story I've never told — other than telling it to Frank. A while back I had an opportunity to say hello to Bruce. Frank's book had just come out, and I thought to myself, "Here's a chance to thank Bruce for the essay he contributed to that book." He wrote a nice little piece for Frankie's book — I wrote the intro, and Bruce had the foreword.

So I just say, "Bruce, I just want to introduce myself. My name's Chris Murray, and I'm the guy who edited Frank Stefanko's book. I want you to know what an honor it was for me to be able to write something and have it published next to something you wrote." That's exactly what I said.

And Bruce turns to me, and he's holding my hand, and he looks me straight in the face and goes, "No, Chris — I'm the one who was honored. Frankie's a great guy, and he deserves everything he gets."

I said, "God bless you, Bruce" and he says, "No, God bless you." And he couldn't have been more generous and gracious. And so, from that day on I've called Frank Stefanko "Frankie." It was such an affectionate thing for him to say: "Frankie's a great guy. He deserves everything he gets."

It's interesting because there were some shots in the new book where I felt some echoes of Frankie's work, particularly of that same era, like the River sessions when Gahr was shooting on the roof.

David took some beautiful portraits of Bruce on the roof. He's got that peacoat on, which is so cool. He looks so much like Elvis to me. He looks great — he's got the sideburns, the hair — he wasn't copying him, he just had that great rock style then that was similar to Elvis. And it's one of the reasons why, in the beginning of my essay, I quote Elvis, because that quote resonated to me with Bruce Springsteen as well.

Elvis says, "I think all any kid needs is hope and the feeling he or she belongs. If I could do or say anything that would give some kid that feeling, I would believe I have contributed something to the world."

Bruce could've said that. It kind of has Bruce's spirit — hope and dreams. The feeling that you belong.

We all know Elvis meant so much to him, as he did to me, and Bruce has so much of that in him. That's why I love this guy. He's got Elvis, he's got Little Richard, he's got Dylan… he's got the soul bands, Otis Redding… he just synthesized all of that great music, and it became his DNA. And I think this book shows a lot of that. It shows those influences, and it shows how Bruce expressed it. His musical DNA.

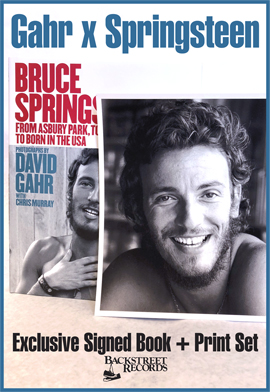

Bruce Springsteen 19773-1986: From Asbury Park, to Born to Run, to Born in the USA is available now from Backstreet Records, a bookplated edition signed by Chris Murray. In addition to the signed book, a limited edition book + print set is available, including a rare Gahr 8x10 printed exclusively for Backstreets, in conjunction with Govinda Gallery and The Estate of David Gahr, in a limited edition of 300.