photograph by Alan Chitlik

This Sunday, January 26, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band will begin a historic run of concerts, their first ever in South Africa. On December 13, 2013, in the wake of Nelson Mandela's passing and following news that the E Street Band would play Cape Town and Johannesburg for the first time, Steve Van Zandt and Dave Marsh recorded a conversation for Sirius/XM satellite radio. Broadcast on E Street Radio — on Kick Out The Jams with Dave Marsh on the Sirius/XM Spectrum music channel and on Live From The Land of Hope and Dreams with Dave Marsh on the Sirius/XM Progress channel — Marsh and Van Zandt talked in-depth about Little Steven's Sun City project that contributed to the fall of apartheid, Mandela's release from prison, and a free South Africa. Transcribed by Shawn Poole.

Dave Marsh: Welcome, Steve Van Zandt. Man, this is a roller-coaster week. You wanna start “up” or “down”?

Steve Van Zandt: [laughter] It’s up to you, man.

Well, actually, y’know something? “Down” was one of the biggest “up”s of my career, and one of the things I’m most proud of having any association with.

Me, too. Yeah.

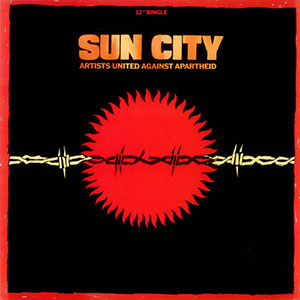

And we’re talking about Artists United Against Apartheid and the Sun City project.

Yeah, you can’t think of it as “down,” really. I mean, ninety-five years old and what a life, y’know? What an amazing life.

"Changed the world” is not a metaphor there.

No, and to do that with 27 years of the prime of your life taken away and still change the world in what people used to consider your old age, in your retirement age, that’s when he got everything done... and that was remarkable.

What I was referring to before... the Sun City record/project... I wrote a book [Sun City: The Making of the Record, Penguin Books, 1985] that was part of that. As time goes by, I'm more and more grateful that I was sick [with stomach-flu], I tried to get out of it and they wouldn’t let me out!

[laughter] No.

[“Sun City”] was done with a remarkable cast of characters, not only in front of the cameras eventually for one of the great music videos of all time, but behind the scenes: Steve, [producer] Arthur Baker, Ricky Dutka, who was [record label] Tommy Boy's attorney and who left the planet way too soon. Who am I leaving out?... Oh, Danny Schechter [“The News Dissector,” who created documentary audio-clip montages for “Revolutionary Situation” on the Sun City album].

Danny Schechter was my first partner. We brought in Arthur Baker. He offered his studio, which was great, and ended up co-producing and connecting us to this new thing which me and Danny were very, very adamant about, which was including these new things called “rappers” on the record, which we can talk about in a minute. And then we should also include [filmmaker] Hart Perry.

Unlike Quincy Jones and Bob Geldof [USA For Africa and Band-Aid charity-benefit organizers, respectively], who were organized when they did this kind of thing, we had people coming in one at a time.

[laughter] Right.

So I would call Hart Perry at two in the morning. “Hart, Miles Davis just walked in. Get your camera and get over here!” [laughter] So it was different.

Well, I think the fact that it could be done that way and it was done that way, particularly with Miles, signifies that it was about something really important that most people in America didn’t know a damn thing about.

It wasn’t an issue. It wasn’t in the papers. It wasn’t in the air. On my list, I had 44 situations around the world I was looking at as I tried to educate myself about what’s going on in the world, which I had never done [before.] I had grown up not being a good student in school or anything else...

A lot of three-minute records, very little school. This is an acceptable “degree” in art.

Yeah. I never read a newspaper. I was completely obsessed with rock 'n' roll until we broke through with The River, and at that point I said, “Y'know, I wonder what’s going on in the world...”

‘Cause you went and saw the world... a little bit of it.

Yes, that’s true. The first trip to Europe had happened and I’ll never forget... This kid came up to me and said, “Why are you putting missiles in my country?” And I was like, “What, are you kidding? Look in my guitar case. It’s a guitar, not a missile. What are you talking about?” And it stayed with me for weeks. I couldn’t get it out of my head.

And it hit me — granted, late in life — oh my god, I’m an American citizen. It had never occurred to me before, y’know? And these people don’t look at us as Democrats or Republicans or policemen or rock 'n' rollers; we’re all Americans over here. And I thought, wow, I wonder what that means. I guess I am putting missiles in his country.

And you were a young man, by the way. You were younger than Nelson Mandela was when he went to Robben Island [the prison in which Mandela was held captive for twenty-seven years.]

Yeah, maybe...

Thirty-one, thirty-two?

Yeah, yeah, in that age [range.] But I thought, my god, I guess being an American citizen, even though we’re not a democracy — we sort of pretend to be — with that goes some responsibility, and I wonder what else I’m responsible for. So I started studying our foreign policy since World War II. And I was just so shocked to find that we were not the good guys everywhere; we weren’t defending democracy everywhere. In fact, out of those 44 situations, we were on the wrong side most of the time.

This was, honestly, a complete shock to me, and I felt that I needed to say something and do something about this, to the degree that I left the E Street Band and dedicated the next ten years to researching and...

...and made a series of fine record albums about this, of which Sun City was the most obliquely yours, but it was yours.

...and made a series of fine record albums about this, of which Sun City was the most obliquely yours, but it was yours.

Well, “Sun City” was gonna just be another song on the Freedom... No Compromise album, my third album, and when I got down there [to South Africa] twice in 1984 to do the research, it started to feel so... I started to witness the brutality. I remember the day, because I went down there completely open-minded. I was reading in the New York Times about the “reforms” they were putting in place, so I went down there giving them the benefit of the doubt. And I remember the day I was in a taxi cab and a black guy stepped off the curb and [the white taxi-driver] swerved to hit him, [muttering] “Fucking kaffir,” which means “nigger” in Afrikaans. And I said [to myself], “Did I just witness that?”, ‘cause I wasn’t really paying attention [at first.] And I remember that moment. It just hit me like, okay, these guys gotta go. This is way beyond another song on my next album. I gotta get some attention for this issue and do something about this.

Did you already know Danny Schechter?

No. I may have met him briefly. I think I’d done an interview or two with him, but we weren’t really that friendly. I called him or he called me when he heard about what I was doing, and he turned out to be a wonderful partner because he was so politically connected and also had such great media savvy... which we needed for this project desperately, because I was not that big a star to sort of be doing stuff like this, frankly. I was not that big a celebrity at the time. I was doing it all from pretty much willpower.

But that was one of the reasons why it worked so well, because it was a) musician-generated and music-generated and b) you didn’t come into it with a lot of... you didn’t see a lot of borders that somebody who comes in just from the political side does see... when you got back here and started doing this.

Yeah, by being down there, I knew there was a disconnect between the conventional wisdom that these guys [the South African apartheid government] were invulnerable, maybe they had the bomb, they’re indestructible, they know what they’re doing, and “we’re gradually putting these necessary reforms in” and all of that. But being down there, I saw that, number one, the Cubans were kicking their ass in Angola, which nobody was talking about, y’know? Just little Cuba was kicking Superman’s ass, okay? [laughter] I thought, well, there’s an interesting vulnerability, first of all. The sports boycott had taken hold, thanks to [the late tennis star] Arthur Ashe, a wonderful guy…

...and [the late poet-activist] Dennis Brutus, who was at the center of all of this activity in North America.

Yeah, and that was just really, really working. First of all, the Afrikaans were... Y’know, I’m in a business of nothing but egomaniacs, and these guys were megalomaniacal beyond anything I’d ever seen. I mean, these guys were unbelievably egotistical and extremely affected by the fact that they couldn’t compete in the Olympics. So, okay, there’s another vulnerability. And I just said, y’know, I gotta figure this out, because these guys gotta go. And I thought, okay, if we can get the cultural boycott to take hold, we can communicate this issue to people through the media. We can then work towards the home run, which was the economic boycott. I saw it as a stepping-stone thing. I came home, and I was quite convinced that this would work if we could pull it off.

And Sun City, the actual [South African entertainment resort] operation, was actively recruiting on the other side, in the alleged state of... Somebody asked me the other day what happened to Bophuthatswana and I said, “Black people took over South Africa and Bophuthatswana disappeared.” [laughter]

Oh, yeah. Well, I guess we should just take a minute to explain. I don’t want to bore everybody, but let’s just take one minute to explain the apartheid system. The concept was... remove the black population back to their so-called “tribal homelands”...

...which would’ve involved the white people leaving, since their [real] “tribal homelands” are the whole place. [laughter]

Yeah, completely phony, and by the way, based on our [Native American] Indian reservations.

Oh, yes.

So, okay, remove the black people to their “homelands.” And I witnessed them knocking down these little shacks and putting people on a truck and taking them out to these wastelands...

...where there were even worse little shacks...

Unbelievable. Okay, so get them out to the “homelands.” Then declare those “homelands” as “independent countries”...

No, as “countries.” “Independent”? Maybe not.

Well, yeah. As “countries," and then bring the black population back in as immigrant labor, having then declared South Africa as a “democracy.” As brilliant as it was evil, right? Bophuthatswana, where the resort Sun City was, was one of these phony “homelands.” And so they were overpaying people to come down…

Entertainers, you mean.

Entertainers, to play Sun City, thereby in real life violating the U.N.boycott, but they were pretending that they were not violating the boycott because they were playing a different “country.”

And they swindled some people into taking the bait.

Yes, they did. And so I sat down and said [to myself], look, the art form of rock is not built for information-information. It’s built for emotional information, usually. In this case, I gotta do information-information. [laughter] I gotta explain what’s going on here as well as I can in the song itself, because it might be our only chance, y’know? So it’s an unusual sort of lyric that you would not normally do. It was more specific, more literal. It was like, okay, let me just tell their story as clearly as I can, because a whole education process is gonna have to take place here.

So that was the concept and the strategy, and when I was down there talking to everybody I could talk to, they wouldn’t let me out on Robben Island to talk to Mandela, and the only guy who [refused to] talk to me was [Chief Mangosuthu] Buthelezi with the Zulu [tribe.] I must mention that South Africa, at that time, was the least tribal of all of the African countries... except for the Zulu, which was a potential problem. And between me and you, I fear [the Zulu] could be a problem again over the next six months, but we’ll see where that goes. I always feared what would happen when Mandela finally passed on; that’s where the trouble’s gonna probably come from. Anyway, he wouldn’t see me, but I met with everybody else, and it was illegal for them to tell me they were in favor of the boycott. Boycotts, as you know, Dave, better than anybody... there’s a tricky bit of business. Economic sanctions, boycotts, embargoes...

...almost always fail. They fail 95 percent of the time.

And when they don’t fail, they can hurt the population that you’re trying to help.

Well, that’s part of the failure.

Very complicated, okay? So I went down there trying to really, y’know, be objective about it. And I talked to everybody, and everybody... it was illegal for them to tell me they were in favor of the boycott. They could go immediately to jail. And they still told me they were in favor of the boycott.

And this was not necessarily always in a room with just the two of you...

No, there were a lot of different situations.

And where more than two people were gathered, there was a spy — or you had to take for granted that there was.

Well, yeah, and three people on a corner was illegal. [laughter] They had it all figured out, man, y’know? So I’m talking to everybody: union leaders, religious leaders, [Bishop Desmond] Tutu, you name it. And people on the street, y’know? Everybody I could talk to. Sometimes it took a little bit of trying to draw them out, ‘cause they were reluctant to say it right away, but eventually in a deeper conversation, they all were in favor of the boycott. I said to them, “Now what happens if this hurts you even more, ‘cause you guys are just really hurting as it is?”

They said, “We don’t care. We feel like we’re in prison, and we don’t care if we suffer a little bit more. It’s worth it for us.”

It’s like worrying whether the [U.S.] Civil War was gonna hurt slaves — literally like that.

Yeah, it was very much like that — exactly.

And that was actually an argument that was made against the Civil War.

Oh, yeah: look at all the slaves that will be out of work [laughter].

It was like, “Can you imagine what the masters will do to the slaves then if this is what they do now?” And, by the way, do you know for sure that South Africa doesn’t have the bomb?

Uh, I think they would’ve used it by now... on me. [laughter] But anyway, so the strategy was in place, and it was just a matter of connecting.

You had to be surprised by the totality of eagerness of performers in the United States.

You had to be surprised by the totality of eagerness of performers in the United States.

Well, it was courageous at the time, because we’re naming Ronald Reagan in the song at the height of his popularity, which people don’t remember right now, but this was, like, a big deal at the time. And every single artist who went on that record felt it could be the end of their career, and they still did it. It was not a social-concern record, “feed the people”...

Yeah, this was way beyond...

It crossed the line from social concern to political. We pointed fingers. We said, “Here’s the problem; it starts right here with our own President.” And we named him. And everybody on that record, man, made a commitment — a very serious commitment — to do that.

Little Steven speaking at a press conference where Coretta Scott King accepted the first $50,000 royalty check (on behalf of The Africa Fund) from artists who created the Sun City album and video. Behind Little Steven (from left) are King, Julian Bond, and Vernell Johnson (Manhattan Records). Courtesy of the African Activist Archive.

You came very close to having a big hit record in the United States. [NOTE: “Sun City” narrowly achieved Top 40 status in the U.S., peaking at #38 on the Billboard charts.]

Well, yeah, that was accidental.

No, it wasn’t. You were with Arthur [Baker], who knew how to make hits. You had been involved in making the hits on Born in the U.S.A.

Well, yeah, but Dave, remember one thing: radio wouldn’t play it. It was too black for white radio, too white for black radio.

That’s the only reason it wasn’t a big hit, ‘cause it was bigger than most... It was actually ahead of its time, because it was a record that sold very, very well without airplay. That’s what happens now, but back then that didn’t happen ever.

That’s right. No, it was strictly MTV and BET playing that video that got the message across. We hit our own apartheid on radio.

It was officially, legally banned in South Carolina.

Oh yeah? I didn’t know that one.

It’s in the book! You’re the one who told me! [laughter] No, but seriously, it was. [NOTE: Marsh’s Sun City book reads as follows: “In South Carolina, one station was told by the Ku Klux Klan that either ‘Sun City’ came off the air or the station and its personnel would face serious consequences. Quite naturally, the record came off the air.”]

It was certainly banned in South Africa, I’ll tell you that. [laughter] But anyway... we were able to measure our success very specifically, because I went and spoke at the [U.S.] Senate. And at that time, I gotta tell ya, Dave, we grow up thinking our congressmen and senators are sort of these guys on high, and they know what’s going on, and they’re very smart. To a large extent they used to be, but I was pointing out where South Africa was on a map to a lot of these guys. And eventually it was their kids, their sons and daughters who came home and said, “Dad, what’s up with this South Africa thing? We want you to do something about it.” And so when that sanctions bill went through and Reagan predictably vetoed it, for the first time in history we overturned his veto.

Really?

Yes, and that was it. We said, “You know what? We just won the war.” Because that was the key: could the Congress, the Senate, from the groundswell, be so aware of this issue to actually overturn a Reagan veto? And they did. And that was it — they fell like dominoes.

Well, it was gonna start causing the United States international problems; that’s part of it. And the other part of it is there was domestic pressure for the first time.

Yes, but the problem overseas was that the pressure was coming from the union movement, which was extremely strong on this, but [then-British Prime Minister Margaret] Thatcher and [then-German Chancellor Helmut] Kohl, together with Reagan — “the Unholy Trinity” — were maintaining that apartheid system, holding it up themselves. When the banks went, though, they couldn’t hold it anymore, man, and they let Mandela out, and the government fell. End of story.

I did a lot of politics in those ten years, Dave. International liberation politics, as you know better than anybody: you gain an inch here, you lose a half an inch there — it’s in inches. This was the only clear-cut victory we will ever see in our lifetime, and it was an amazing feeling.

Well, to anybody out there who’s trying to do social change with music, and lots of people are, there are a lot of lessons that can be learned [here.]

It’s nice, isn’t it, that we have an example to show that you don’t have to necessarily be a big star or whatever to accomplish something.

Well, like Danny Schechter and Hart [Perry] and a couple of the other people involved... you know, we didn’t play guitar, so we read. [laughter] So we had started earlier, and I caught the tail-end of the Civil Rights Movement myself, and the meat of the anti-war movement during the Vietnam period. And those were wins. Wins with limits, but all wins are wins with limits.

Yeah — except this. [laughter] This actually was a win. [more laughter]

True. Then you move on to “freedom is not without its complications.” And you don’t know that until you’re free.

Well, that’s true, and on that subject, on my second trip down there I tried to organize a post-apartheid economic summit. And even my friends down there were lookin’ at me like, “Uh, you know, this optimism thing is really getting out of control.” [laughter] They couldn’t conceive of a post-apartheid situation.

And I was, like, “We have to plan for this, okay? It’s gonna happen; it’s gonna happen. Right now we need to reward the companies that have withdrawn and, frankly, punish the companies who are staying. Start with that, and then let’s work into a situation where we can start to plan how to deal with this ridiculous, rampant poverty and all the other things.” I couldn’t get anybody to actually sit down and even think about that. It was so unthinkable to them.

Well, just in true temporal, historic time, you were seven years ahead of your time.

Yeah, maybe ten — because [Nelson Mandela] was elected [South Africa’s first post-apartheid President] in ’94, right?

Oh yeah, that’s right. Ten — it’s ten. But let’s talk about [the passing of] President Mandela for just a minute and then turn to the “up” side. [laughter] Although President Mandela, I imagine, was himself the “up” side. You met him.

Twice. Yeah, I gotta tell ya something. I met a lot of people in my life. I never met anybody like him. He had an aura that you read about in, like, the Bible, okay? I mean, he had a religious... and I don’t mean like meeting a priest. I mean he had a religious-leader vibe, like running into John the Baptist or the Buddha or something. I’m not exaggerating. He had that vibe, just emanating warmth and kindness and understanding. You felt good being in his presence. Shaking his hand, you felt this electricity. It was something else, man.

He was the only person who believed in 1984 what you believed, actually. If he had been out on the street, you would’ve had one guy agreeing with you. [laughter]

Yeah, yeah.

I’m laughing about it, but that’s true; he never wavered about “we will win this thing.”

No. He evolved, as we all know. We did one Wembley [Stadium concert in London] to get him out of jail, and then another Wembley to celebrate him getting out. I met him there, and then they chose me to run their fundraiser when he came to New York, and I brought in Bobby DeNiro and Eddie Murphy and Spike Lee and we did the dinner at the Tribeca Grill. He came down and spoke and was very enthusiastic about what we had done.

You could tell by the way he says... Does he say “Little Steven” on the stage at Wembley? I listened to the speech last week, and I was listening for that.

I’m not sure if he mentioned me or not.

He did mention you.

Yeah?

He just says your name, but he pauses before and after it, so he puts some emphasis on it.

Wow, that’s nice. I didn’t even remember that. That’s wonderful. But anyway, [at Tribeca Grill] he congratulated us on the universal communication of music and how effective that can be and all that, so he was really quite hip about the power of using the media and all that. It was wonderful to meet him.

You know, when I went down [to South Africa] the first time, I’m trying to do all these meetings. Then I had to do some secret meetings and get away from anyone resembling a handler or political operative. And I snuck into Soweto, where they were under [military isolation.]

Yeah, they were surrounded.

So I snuck in and met with AZAPO, the Azanian People’s Organisation, who were like a more radical, violent version of our Black Panthers. They were actually on the front lines blowing shit up and stuff like that. And I had to plead my case to them, because they were sort of the hard line. And I said to them, “Look, all due respect, man, you’re not gonna win this fight. I don’t blame you for picking up guns and defending yourselves.” Because it was brutal; the regime down there was brutality. “I don’t blame you, but you’re not gonna win. You cannot win this way. Let me please try my idea, and I’m gonna win this war for you in the media, on TV.”

Now this already would’ve been a stretch for most people, but when you’re trying to tell this to people who don’t have electricity, that you’re about to win their war on a box that you plug in somewhere, they looked at me like, “This guy is really nuts.” [laughter]

If you thought Stevie’s kidding... the truth of the matter is that South Africa, for a very, very long time, well into the '70s or early '80s, did not have television for exactly this reason. There was no television if you’d been talking to a white South African.

Yeah, because when you’d go into Soweto, which was this huge area — I mean, it’s huge — you’d see, like, two or three feet of fog all over the ground. No lights. And it just had this very, very surreal feeling to it, because that was all from the coal-fires and whatever they were burning for heat. So it was like a really interesting movie-scenario sort of thing.

And I met with AZAPO, who had a very frank conversation — I was talking to the translator — about whether they should kill me for even being there. That’s how serious they were about violating the boycott. I eventually talked them out of that and then talked them into maybe going kinda with my thing.

Tthey showed me that they have an assassination list, and Paul Simon was at the top of it. [NOTE: In 1986, Paul Simon recorded tracks for his Graceland album in South Africa, in direct violation of the cultural boycott.] And in spite of my feelings about Paul Simon, who we can talk about in a minute if you want to, I said to them, “Listen, I understand your feelings about this; I might even share them, but...”

In January 1987 the American Committee on Africa and The Africa Fund hosted a reception for ANC President Oliver R. Tambo. Above, Africa Fund chair Tilden LeMelle presents Tambo with a check for more than $100,000 from money raised from the Sun City album (in all, the Sun City project raised more than $1 million for ANC projects to meet the educational, cultural and health needs of South African exiles; to aid South Africa political prisoners and their families; and aid the anti-apartheid education work in the United States). From left to right: Little Steven, Tambo, LeMelle, and reception MC Harry Belafonte. Photograph by David Vita, courtesy of the African Activist Archive.

I was with you the first time you saw Paul and talked to him about this, at [entertainment attorney] Peter Parcher’s 60th birthday party.

That’s right, that’s right, that’s right! I’m glad you were a witness, because wait’ll you hear the latest on that. Anyway, I said to them, “Listen, this is not gonna help anybody if you knock off Paul Simon. Trust me on this, alright? Let’s put that aside for the moment. Give me a year or so, you know, six months," whatever I asked for, "to try and do this a different way. I’m trying to actually unify the music community around this, which may or may not include Paul Simon, but I don’t want it to be a distraction. I just don’t need that distraction right now; I gotta keep my eye on the ball.” And I took him off that assassination list, I took Paul Simon off the U.N. blacklist, trying to...

You mean you convinced them to take him off...

Yeah, because this was a serious thing...

Because this was gonna eat up the attention that the movement itself needed.

Yes, and the European unions were serious about this stuff, man. You were on that [U.N. blacklist], you did not work, okay? Not like America, which was so-so about this stuff, man. Over there, they were serious about this stuff, you know? Anyway, so yeah, this was in spite of Paul Simon approaching me at that party saying, “What are you doing, defending this communist?!”

What he said was, “Ah, the ANC [African National Congress, the organization of which Mandela was President at the time of his arrest and imprisonment], that’s just the Russians.” And he mentioned the group that [murdered black South African activist Steven Biko] had been in, which was not AZAPO...

Was he PAC [Pan-Africanist Congress]?

It doesn’t matter [for this story], but [Paul Simon] said, “That’s just the Chinese communists.”

Yeah, yeah. And he says, “What are you doing defending this guy Mandela?! He’s obviously a communist. My friend Henry Kissinger told me about where all of the money’s coming from,” and all of this. I was, like, all due respect, Paul...

I remember it very vividly, because it was aimed at everybody standing in the general direction.

Yeah, but mostly he was telling me.

Well, yeah, you were the one... Everybody knew who to get mad at first. [laughter]

He knew more than me, he knew more than Mandela, he knew more than the South African people. His famous line, of course, was, “Art transcends politics.” And I said to him, “All due respect, Paulie, but not only does art not transcend politics... art is politics. And I’m telling you right now, you and Henry Kissinger, your buddy, go fuck yourselves.” Or whatever I said. But he had that attitude, and he knowingly and consciously violated the boycott to publicize his record.

Well, to make his record. That’s the violation of the boycott — to make his record.

Yeah, and he actually had the nerve to say, “Well, I paid everybody double-scale.” Remember that one? Oh, that’s nice... no arrogance in that statement, huh? [laughter]

Now, the punchline. Cut to 30 years later, or whatever it is. He asked me to be in his movie [Under African Skies, the documentary on the making of Graceland, included as a DVD in the album's 25th anniversary boxed edition]. I said, “Alright, I’ll be in your movie, if you don’t edit me. You ready to tell it like it is?”

He says, “Yep.”

“Are you, like, uh, apologizing in this movie?”

“Yep.”

“Okay. I’m not gonna be a sore winner. I’ll talk to you.”

I did an interview. They show me the footage. Of course, they edited the hell out of it to some little statement where I’m saying something positive about Paul. [laughter] And I see the rest of the footage, where he’s supposedly apologizing, with Dali Tambo [founder of Artists Against Apartheid and son of late ANC leaders Adelaide and Oliver Tambo]. He says, “I’m sorry if I made it inconvenient for you.” That was his apology.

In other words, he still thinks he’s right, all these years later!

You’re the only person who’s ever met Paul twice who thinks that’s surprising. [laughter]

I mean, at this point, you still think you were right?! Meanwhile, that big “communist," as soon as he got out of jail, I see who took the first picture with him. There’s Paul Simon and Mandela, good buddies. I’m watchin’ CNN the other day. Mandela dies, on comes a statement by Bono and the second statement’s by Paul Simon. I’m like oh, just make me throw up. You know, I like the guy in a lot of ways, I do; and I respect his work, of course. He’s a wonderful, wonderful artist, but when it comes to this subject, he just will not admit he was wrong. Y’know, just mea culpa. Come on, you won! He made twenty, thirty million dollars at least, okay? Take the money and apologize, okay? I mean, say “Listen, maybe I was wrong about this a little bit.” No.

Well…unfortunately we live in a country where the money means you don’t have to apologize, and let’s leave that there.