Toward the end of Reunion-era concerts with the E Street Band, Bruce Springsteen would underscore a crescendo with the affirmation that he could "promise you life right now!" Not an everlasting one, he'd say, as if he needed to draw a line between what he was offering and something else.

Toward the end of Reunion-era concerts with the E Street Band, Bruce Springsteen would underscore a crescendo with the affirmation that he could "promise you life right now!" Not an everlasting one, he'd say, as if he needed to draw a line between what he was offering and something else.

Now that frequent exhortation gets backed up on Letter to You, Springsteen's 20th studio LP, recorded live in his New Jersey home studio with returning co-producer Ron Aniello. A gust of autumn wind blowing down the boardwalk, Letter to You heralds a change of seasons as Springsteen assesses his own life and summons ghosts, backed this time by the power of the E Street Band.

Letter to You follows the thread of the past four years, marked by a best-selling autobiography and its stage companion, Springsteen on Broadway. It recalls The Who By Numbers, which Pete Townshend composed in frustration at the cusp of 30, a response he characterized as an inability to write new music for The Who. Both back-to-basics and introspective, it remains one of Townshend's most deeply moving records.

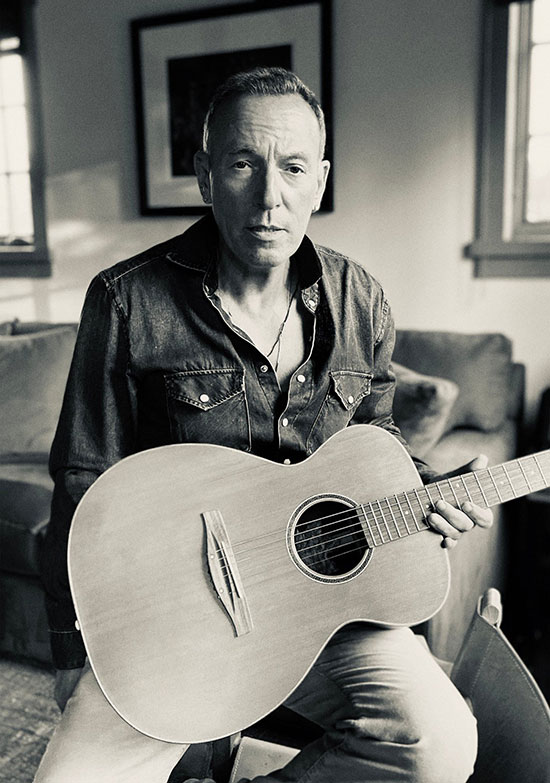

Nearing 70, Springsteen faced a similar problem — writing for the E Street Band — until one day in 2019 when he didn't. Playing a bespoke guitar he'd received as a gift from an Italian fan outside his Broadway show, he moved from room to room in his house, writing and capturing the songs on his iPhone as he went. He skipped the demo-making process, convened the E Street Band, and taught them the songs on the spot. They finished recording most of it in four days.

Springsteen with the guitar that inspired Letter to You, October 2020 - photograph by Joe DeSalvo

In nearly every respect, the new LP stands in contrast to his last one, Western Stars, which, with its labyrinthine recording history, lush arrangements, and decidedly produced feel, spent years on the shelf. Though it took the scenic route, Western Stars looked carefully at archetypes of the American Male in suspense. Letter to You takes the measure of a more balanced life — more conventional, too, but closer to realizing potential.

Its cover image shows Springsteen in Central Park, evoking a Lion in Winter look. And there's no getting around the fact that Letter to You grapples with aging and mortality, topics that have come up in earlier songs like "Kingdom of Days," "Western Stars," "The Rising," and even "Valentine's Day."

Gone is the comparatively whimsical, upbeat "Cadillac Ranch." Now, Springsteen writes about the end of life in a far more nuanced tone, and the subject frames an entire album, from the "big black train coming down the track" in the opening line to the titular declaration of "I'll See You in My Dreams" at the end. In between, the music often rages against the dying of the light. But if Letter to You is a resistance record, it's rooted in the affirmative: we are alive. For now.

Photograph by Danny Clinch

That's why there's still ample space for joy, as in the ringing rejoinder in "Ghosts": "I'm alive and I'm comin' home!" It's the gospel in the chorus — Springsteen's own shorthand for his bifurcated approach to songwriting, which counters the blues in the verses. Except this time out, lines get blurred, letting the blues seep into the chorus, as they do in the title track:

In my letter to you I took all my fears and doubts

In my letter to you all the hard things I found out

In my letter to you all that I found true

And I sent it in my letter to you

Springsteen establishes intent on the LP's first song, "One Minute You're Here." Each of its verses takes on a different life cycle issue in a simple, repeating pattern. No mere writing exercise, it reveals not the gray areas in life but the absolutes. A train rolling over a penny increases its value somehow — a tangible example of transformation, followed by a spiritual one as the song ends.

Evocative endings appear frequently in the songbook, whether outside a town courthouse (the flag being lowered in "Frankie") or in the tunnels uptown (where the Magic Rat meets his fate in "Jungleland"). They stand out on Letter to You: a solitary walk from the tracks to the river, or that "one last beer" at the Legion Hall. "Last Man Standing," the first new song written, is an ending of sorts, as Springsteen proves himself an empathetic guardian for his deceased bandmate George Theiss and the other musicians who came together as The Castiles in the mid-1960s.

Vellum inner sleeves are included in first pressings only of the vinyl 2LP set

They may well dwell in a "House of a Thousand Guitars," which glides on an intriguing title and Roy Bittan's melodic piano. Whether it's a protest of "the criminal clown," a celebration of music as a cathedral, or even a vision of the afterlife remains an open question. It could be all three, and it's a good tune, but its lyrics present an instance where Springsteen relies on feel and a sense of wonder — which comes across — as sufficient to carry the song. It's hard to square this repetitiveness and weaker imagery here with Bruce's instinct for precision.

It's a rare misstep in a project that took so little time to complete. Songs came to Springsteen over the course of a couple weeks, and he recognized them as the basis for an E Street Band record. (In addition to "Rainmaker," the LP's credits indicate "One Minute You're Here" and "Burnin' Train" predate the music written in 2019.)

That speed is remarkable for Springsteen, who famously took six months to complete his greatest song, and two years to record Born in the U.S.A. — sifting through easily six times as many songs (granted, he kept writing as he recorded). Back then, the sounds and a conceptual arc eluded him, which kept those respective projects going.

Not so with Letter to You. Although mining your own life for inspiration at age 70 is a tricky proposition, Springsteen is nothing if not self-aware. As a result, it sounds like a high-conviction record, much as Born in the U.S.A. does. That LP had everything going for it, but it was one nonetheless about which Springsteen harbored "some ambivalence" (beyond the title track). It's unlikely we'll ever hear him say that about the new album. Most artists will crow about how great their new record is; Springsteen can do that now (as well he should) and is wiser still to point out its complexities, as he has in Thom Zimny's Letter to You film and attendant press (read Caroline Madden's film review and Christopher Phillips's interview with Zimny).

Photograph by RobDeMartin

Though his songs spilled onto the page marked E Street, the band's imprimatur sounds even clearer. Granted, it's a familiar sound, down to individual tones of guitars and saxophones. The E Street Band doesn't break new ground for Letter to You; rather, it reclaims its older one, and with grandeur: freed from the relative dullness of laying down a record in piecemeal fashion (known as "tracking"), it simply owns these new songs.

The return to ensemble imbues the new songs with the drive and energy that carried The River and Born in the U.S.A., predecessors in the Recorded Live category (okay, mostly). That directness and intent goes straight to something Springsteen wrote about in the Songs compendium: "For most, music is primarily an emotional language; whatever you've written lyrically almost always comes in second to what the listener is feeling." The E Street Band tips the scales here with what it does best: it plays.

That's obvious from even a cursory listen to the propulsive, shovel-all-the-coal-in feel of "Burnin' Train." It's not the LP's lyrical high-point, but it is clearly a love letter within the letter, and a way out of "This Depression" — it's a momentum-maker. Forget that there has been a host of other trains: Downbound, Leavin', Tucson, one bound for the Land of Hope and Dreams, and just for a second, even the one in the opening line of "One Minute You're Here." Despite déjà vu in the imagery, it serves Springsteen's highest purposes.

The E Street Band reminds us of the power of congregation, disrupted in a time of pandemic, a frayed national identity, and especially by the distortion of social media. Veering toward something higher, Letter to You features little in the way of politics, at least of the electoral variety; only "Rainmaker" speaks directly to the election year landscape (were it not for Springsteen's own candor, one might not know that the song dates back to the George W. Bush administration).

Instead, the record plays the long game. Its sequence takes the listener through frames as if they were moments that flashed before Springsteen's eyes as he moved from room to room (which is precisely how many of us will play these back). That stream-of-consciousness feel extends itself over many of the newly-written songs. But hooked up to the can't-miss sound of the music the E Street Band makes? Springsteen could be singing about the color of the sky — which in fact he does — and you'd still find yourself humming along.

Still from the Thom Zimny film Letter to You

Many styles take turns on the record, whether the classic 1975-'85 sound of E Street, the plaintive Tom Joad-era vocals, or even the "New Dylan" sound of the early '70s. It's the last of these turns that proves especially compelling, when Letter to You reimagines music Springsteen wrote nearly a half-century ago. What might the veteran rocker in his 70s tell the youthful wordsmith, grappling with all sorts of imagery, characters, and storylines? How about "Listen to this."

Three early-era songs Springsteen chose for the E Street Band — "Janey Needs a Shooter," "If I Was the Priest," and "Song For Orphans" — make for a late-innings masterstroke, not only for the musicianship, but also to confirm the idea of committing oneself to creativity in the first place. Springsteen has fondly invoked Jackson Browne, who once remarked that "a good song stays written." Here, we get three.

Each exemplifies the longer song structures that dominated Springsteen's early work, with edges that he would shape in different ways as his writing matured. Why they show up on Letter to You isn't fully explained: "Janey Needs a Shooter" could stand as an allegory to the Me Too era just as easily as it could as a prequel to "Point Blank"; regardless, it gets a smart, well-deserved final arrangement, as do the other two, binding past and present.

And when Springsteen counts them off, they're transformed, too: they're not the "old songs" anymore; rather, they're an indivisible part of the joy that comes when the E Street Band kicks in. No work has quite the sweeping feel they conjured for Born in the U.S.A., and Magic stands as a work of perhaps even greater focus. But these songs help complete a cycle, an idea central to this record.

And that, my fellow listener, is where we take our rest. "I'll See You in My Dreams" is Letter to You at its most bittersweet, not a postscript but a clear message of acceptance and affirmation. By the end, Springsteen's voice fades out like never before, with just the sparest accompaniment, similar to how the record began. Except here, he sounds content. And renewed, having unpacked so much in the course of 58 minutes.

So what do you do when the past turns up at your front door? Invite it in, then turn the music up. Really loud.