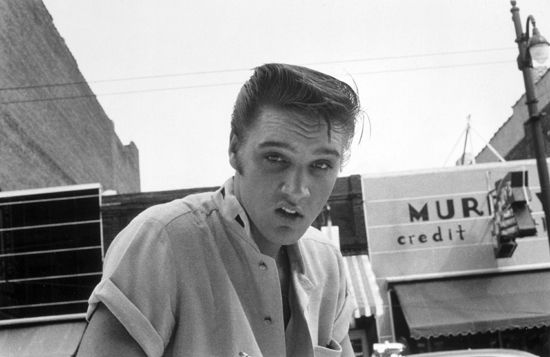

Photo courtesy of ABG / Graceland Archives

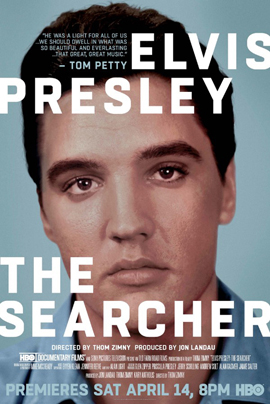

Elvis Presley: The Searcher, a two-part, three-hour documentary premiering this Saturday, April 14, on HBO, is unlike any other Presley documentary that has come before. From the outset — a telling quote from co-producer Priscilla Presley from which the doc gets its name, then a scene from Elvis' triumphant 1968 "Comeback" NBC-TV Special — The Searcher's mission is clear: to highlight the musical, creative journey of one of the most influential figures in popular music, from life to death, to explore Presley's vision in the context of the music he loved and that he created.

Elvis Presley: The Searcher, a two-part, three-hour documentary premiering this Saturday, April 14, on HBO, is unlike any other Presley documentary that has come before. From the outset — a telling quote from co-producer Priscilla Presley from which the doc gets its name, then a scene from Elvis' triumphant 1968 "Comeback" NBC-TV Special — The Searcher's mission is clear: to highlight the musical, creative journey of one of the most influential figures in popular music, from life to death, to explore Presley's vision in the context of the music he loved and that he created.

The Searcher was helmed by a team most often associated with Bruce Springsteen: directed by his archivist and go-to filmmaker Thom Zimny, and produced by Springsteen manager Jon Landau. Those familiar with the pair's collaborative work on previous documentaries such as Wings For Wheels: The Making of Born to Run and The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town will recognize a similar focus on artistry — on the genesis and creation of the music over personality, mythology, or other distractions. To paraphrase Tom Petty, The Searcher cuts through the clatter and noise and focuses on the art of Elvis Presley.

While The Searcher covers the essential parts of Presley's personal life (his geographic trajectory from Tupelo to Memphis, his relationship with his parents, his marriage to Priscilla), it above all serves to emphasize his status as someone "born with that commitment to the music," as record producer Bones Howe puts it. For example, one of Priscilla's lasting initial impressions of Elvis (they met when Elvis was stationed in Germany) is of the records he was listening to: acts like the Platters and Faye Adams ("Shake a Hand"), artists that Priscilla was unaware of at the time. Telling elements like that are what further the narrative here, over more common chestnuts such as Presley's meeting with President Nixon — which, having no bearing on the creative process, is left out of The Searcher's story altogether.

As Landau told Backstreets, "the film is not interested in being salacious, it's not interested in being judgmental." That desire to stay away from melodrama, that desire to view Elvis "in an empathetic way," as Landau told me, serves to create a portrait of Presley as artist, framing his life in terms of personal issues only when they affect his craft.

Photo courtesy of ABG / Graceland Archives

Drawing on testimonials and observations from a number of Elvis scholars, fans, and friends, the documentary tracks Elvis Presley the artist, from his poverty-stricken roots through to his massive success and eventually to his untimely though not altogether surprising death at the young age of 42. Add to that the use of rare footage — performances, home movies, geographically appropriate film — a beautiful score by Pearl Jam's Mike McCready, and new interviews, and The Searcher paints a powerful portrait of Elvis that combines his unprecedented fame, social impact, musicianship, and humanity.

There are some real coups in terms of speakers, as well — and that's aside from producers Priscilla Presley, Jon Landau, and Elvis inner circle member Jerry Schilling, all of whom provide commentary in the doc. A comprehensive list of all of them would take up an article of its own, Zimny having conducted more than 50 new interviews for the project. Chief among them is renowned songwriter/producer/Stax Records employee David Porter, who, with Isaac Hayes, wrote some of the all-time Memphis soul classics ("Hold On, I'm Comin'," "Soul Man," etc.). Porter brings credibility to The Searcher that previous Presley documentaries have often lacked. A mere six years Elvis' junior, he has a bird's eye view of post-World War II Memphian African-American culture that few living musicians can lay claim to. His eyewitness account of Presley's rise to fame in that context is essential to any serious understanding of Elvis as an artist.

Photo courtesy of ABG / Graceland Archives

Porter, who refers to Elvis as having "soul" in The Searcher, spoke with Backstreets and told me of seeing Elvis as a youth, hanging respectfully around African-American night clubs on Beale Street, and of crossing paths with him later. Porter's pre-Stax duo with Hayes was hired to play a private party for Elvis; later, Porter and Presley ran into each other at Stax Studios in 1972, when Elvis was recording there and Porter was producing an album by the Sweet Inspirations, who sang backup in Presley's band. Porter clearly felt an affinity with the man, and he speaks highly of Elvis's lifelong commitment to and appreciation of African-American music.

Another key interviewee — and an often unsung hero in the fight to present Presley in a positive light — is Ernst Jorgensen, who since the early '90s has overseen the reissues of Elvis' vast recorded work for RCA and its Elvis-centric subsidiary, Follow That Dream. Jorgensen's attention to detail and quality control — not to mention his exhaustive knowledge of Elvis's recorded legacy — has been the aural counterpart of The Searcher, making sense of a body of work that was once confusingly released and re-released, often with no regard for chronological accuracy. Jorgensen's inclusion in the documentary, considering its aims, was an absolute must. His understanding of the ups and downs of Elvis's life in the studio plays a critical part here.

Attention rightly belongs with the sheer quality of the other interviewees: the roll call is staggering. Bruce Springsteen — no stranger to fame, himself — weighs in throughout the film. He compellingly describes Presley's voice as having a "beautiful geography to it." The voice of the late Tom Petty plays a key role, too, providing an intuitive insight to rock 'n' roll stardom as well as a knowledge and understanding of the music that consistently gets to the heart of Elvis's artistry. Musicians like Robbie Robertson and Emmylou Harris weigh in, while music and folklore authorities like Dave Marsh, William R. Ferris, Portia Maultsby, and Warren Zanes provide an informed, scholarly — though never dull — perspective that helps put Elvis and his music into a much needed historical context, making sense of the times and places that surrounded Elvis on his artistic journey.

Zimny's decision to refrain from showing "talking heads" — viewers see each speaker's name on the screen, and that's it — keeps the documentary flowing in a way that suits its seemingly always on-the-move subject, inserting a kinetic energy to the proceedings that enhances the experience. Through this method — with a visual focus on the subject himself, utilizing some astonishing fresh images coupled with rare footage from the Graceland archives — the viewer experiences the feeling that they're actually moving along with Elvis.

Photo by Alfred Wertheimer. Courtesy of the Estate of Alfred Wertheimer, © Alfred Wertheimer

The Searcher is broken up into two parts, in basically the same way that Peter Guralnick's groundbreaking biographies of Elvis were: part one covers Elvis's youth, his experiences on Sun Records ("high art," according to Petty), his meeting and working with Colonel Parker, his signing to RCA Records, the first four films he made between 1956 and 1958, and his induction into the US Army in 1958. Part two covers his post-Army career (he was relieved of active duty in 1960), what Springsteen refers to as "life for Elvis after Elvis": the subsequent years of movies; the accompanying occasionally great, sometimes good, but largely bland soundtrack moments; his return to greatness in the late '60s starting with the 1968 Singer Presents… ELVIS special; and his eventual decline.

The Singer special — retroactively referred to as the "'68 Comeback Special," due to the revitalizing effect it had on Presley's career after years of increasingly generic though successful movies — is referenced many times during the documentary. It serves as a kind of frame, and for good reason: it represents a phoenix-like moment that proved not only that Elvis still had "it," but also that he was capable of revisiting his catalog. In it, he performs "Heartbreak Hotel," among others, while proving himself to still be relevant with the closing number — one of this writer's favorite Presley performances — the phenomenal, socially relevant "If I Can Dream." Landau himself refers to the '68 Comeback as if its purpose were to "erase the last seven years of soundtracks," and it's hard to disagree with that assessment.

Photo courtesy of ABG / Graceland Archives

No comprehensive Elvis Presley documentary can avoid dealing with the controversial management style that Landau refers to as "the tragedy of the old style of management," employed by Presley's infamous manager, "Colonel" Tom Parker. It's one of several areas where the expertise of Landau really comes to the fore. Landau's observations on Parker's technique — "keeping the blinders on," as he puts it — shed a clearer light on the Colonel's management methods and the hindrance they would prove to be to Elvis's career. Parker, an illegal, Dutch immigrant, whose lack of U.S. citizenship prevented Presley from touring overseas, was, as Schilling points out, "not a creative guy," though he was a guy who was damn good at promotion, and at making money. That these took priority over artistry time and time again is one of the sadder elements of Elvis' career.

But then there's the music, always the music. The documentary consistently emphasizes the importance of music in Elvis's life, from his days in Tupelo to his excursions into African-American clubs on Beale Street to hear blues and R&B — excursions that were rare for a white guy, at the time, as Porter points out — to his love of country and western and the pop music of the day. From Dean Martin to Elvis's obsession with white and black gospel, it was all accessible on the radio and in person in his adopted hometown of Memphis.

But then there's the music, always the music. The documentary consistently emphasizes the importance of music in Elvis's life, from his days in Tupelo to his excursions into African-American clubs on Beale Street to hear blues and R&B — excursions that were rare for a white guy, at the time, as Porter points out — to his love of country and western and the pop music of the day. From Dean Martin to Elvis's obsession with white and black gospel, it was all accessible on the radio and in person in his adopted hometown of Memphis.

Photo courtesy of ABG / Graceland Archives

The decline in Elvis's health, starting in the early '70s when he was performing regularly in Vegas — a period that Dave Marsh says made Elvis "vulnerable" — is covered with grace. While Elvis's health may have been deteriorating, Landau's 1971 review of a concert at the Boston Gardens (part of which he reads in the film, to great effect) shows that the music and the star could still deliver the goods.

There are some fairly stunning revelations to be found here, even for the hardcore Elvis fan, details about recording sessions, song inspiration, and live gigs. Band members are given their due and their say here, too. And having Priscilla Presley, Jerry Schilling and fellow "Memphis Mafia" member Red West on board gives the viewer an insider's look into Elvis's inner circle — again, in a uniquely non-sensationalized way — that provides a deeper understanding of the man than second-hand accounts or sensationalized stories could reveal. Presley and Schilling saw a side of Elvis that damn near no one — certainly no one living — was privy to. Their objective take on the ups and downs of Presley's personal life with regard to his career is absolutely priceless. One of my favorite moments, recounted by Schilling, takes place when Elvis learns of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. Presley, visibly saddened by the news, looked down and simply said, "He always told the truth."

If one could only pay one compliment to The Searcher, it would be that it, too, tells the truth. Bad decisions — and those are part of the Elvis Presley story, make no mistake — are not glossed over: they are confronted and examined in a way that brings a certain dignity to the documentary's subject, a dignity that he has heretofore been often denied. But Elvis Presley's lifelong "search for emotional music," as Warren Zanes calls it, is presented in an honest, contextual, inspiring way. It's no less than Elvis deserves.